Our Electric Controls

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

The infrastructure of electrical power in Seoul’s Namdaemun Market is used as a subtle control over the market’s spatial extent. A white enameled-steel prefabricated cart module has proliferated across the market and is used in a wide variety of ways, selling everything from jewelry to hats, socks, and a range of freshly prepared food. The cart is approximately 1.5 meters long by 90 centimeters wide, and has storage for goods in the wheeled base. Panels and roof unfold, increasing the surface area for selling and storage.

Some 270 of the carts were supplied in December 2010 by Bizboom Street Furniture as part of a city government–led redevelopment or beautification project. Pressure on the market area is exerted by the nearby commercial districts and financial center, and the pressure to limit the extent of the market to a proscribed territory is strong. This is achieved by limiting access to electricity.

The carts require electricity to function, not only for lighting but also to unfurl from their closed form; a motor is deployed to elevate the roof structure—a seemingly extravagant feature of the design which, unlike cart designs seen elsewhere in the city, does not include an engine to drive the cart. Instead, the cumbersome carts are moved from their storage areas in long trains by a quad bike.

The market has a center as a result: a concentration of the modules along the central street, with increasingly ad hoc and informal structures toward the fringes. The informal carts are edged out, the market controlled by the rationalized unit that relies on stable infrastructure in order to function. The carts can be seen as an instrument restricting and limiting the activities of vendors who would otherwise challenge the boundaries between the legitimate and illegitimate.

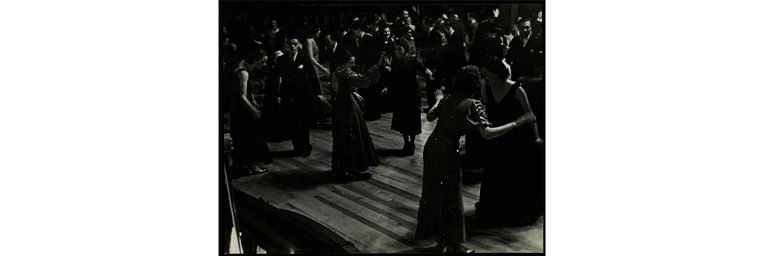

In 1940s Britain preserving a good head of curls was a social duty. Luscious curls promised high social and economic status, a good personality, solid intellect, and sex appeal (Malcolmson 2012). Once or twice a year, those not blessed with natural curls would spend up to six hours plugged into a machine that would pump current to electrical rollers and cook their hair. To produce a subtle wave thus required electricity, connecting beauty and fashion with a male-dominated electrical industry.

Wartime fuel shortages did not dampen enthusiasm for luscious locks. “Think of all the ladies who have theirs done daily—it’s a vast amount of electricity used on hair curling,” complained one husband whose wife was off getting a perm (Mass Observation Archive 1942). But even though curls were identified as a drain on the fuel economy, the cultural pressure for this beauty paradigm meant that curls survived the war, in spite of the danger of being hooked up to electricity during an air raid.

During the fuel crisis of 1947 government regulations limited the operating time of permanent-waving machines, although hair dryers were permitted to run all day (see Robertson 1987). This selective hair-care choice revealed the gendered management of the grid and the conflicting priorities for allocating power. One woman, for example, wondered whether this counterintuitive restriction was a result of men misunderstanding the perming process (Mass Observation Archive 1947). She suspected that men, never having been subjected to a painful perm, might imagine the machine running for the whole three hours rather than in short eight-minute bursts. Or, placing less value on curls than women did, maybe men just considered shampoos more essential than perms.

In Angola, many people are afraid of having their water and their lights cut off. Not in the literal sense, though that happens too: infrastructure is weak. Rather, this condition is invoked as metaphor: if your lights and water are cut off, it means you have no access to power. There is no point seeing like a state if the state chooses not to observe you.

Power was (?) the president, and his party the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). From him did all blessings flow. The president was in Luanda (or Paris, for medical treatment), which was far away for most—even Luandans. Space is political, and multiple grids overlay one another: flight paths, eye level, cables under ground.

Like tiny churches, like shrines, like bimahs, like prayer mats, sockets are where power and the individual connect. Every family must forge a relationship with them. Houses are all built differently, but the particularities of how they meet the grid(s) reveal the orientation of entire worlds.

I rented a room from Dona Christina. She lived in the highest apartment of a once-grand building. The noise of neighboring generators grated on her nerves; she didn’t need one herself. She accessed a semisecret socket, connecting to the power that never failed: the mains. After several months she taught me the system. Invariably, at touch, the light and water returned. Before then I waited in darkness, or nearly electrocuted myself unsuccessfully rearranging the heavy blue plugs.

Christina’s access came through her husband, who was in the military. Such privileges are common throughout the world. We would see them more easily if only we attended to sockets: the space where special connectivities are neither airborne nor underground. Sockets are tangible, spatially configured, politicized, charged at the borders.

Malcolmson, Patricia. 2012. Me and My Hair: A Social History. Gosport, U.K.: Chaplin Books.

Mass Observation Archive. 1942. “Fuel Use Survey.” TC Fuel 1937–1947, 68/2/B.

Mass Observation Archive. 1947. “Panel Responses.” TC Fuel 1937–1947, 68/5/C.

Robertson, Alex J. 1987. The Bleak Midwinter: Britain and the Fuel Crisis of 1947. Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press.