Our Electric H₂O

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

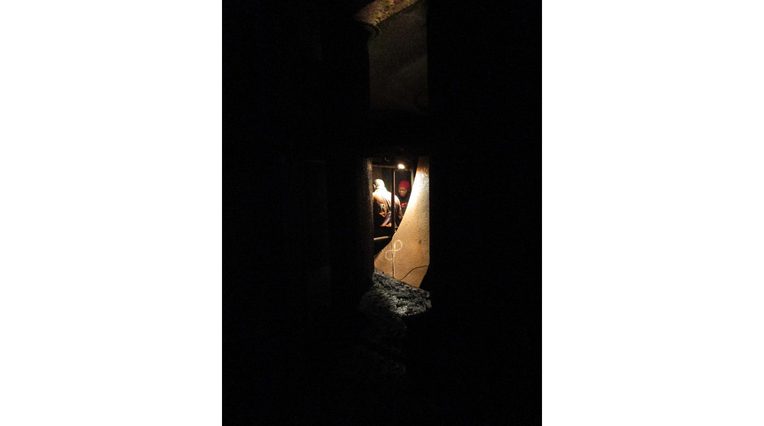

The engineer leads me inside the G24 Francis hydro-electric turbine, which is currently under rehabilitation. The heat, the sound, and the gentle trembling from the neighboring turbine give me the impression of being inside a living organism. He makes reference to “the heart of the plant” as he guides me down a multitude of stairways, ladders, corridors, and little doors into the bâche spirale of the turbine. This eight-meter-wide spiral case feeds the runner with water, which makes it rotate.

The references that engineers make to organs when they discuss different parts of the turbine exemplifies the tendency of humans to give anthropomorphic characteristics to technological creations. And here we were, right next to the roue turbine, the mother organ of the machine. Normally, water runs through the spiral case at the speed of 320 m3 per second; however, the spiral case’s floor was covered with a thick layer of sand. From the other end of the corridor, a stream of water runs toward us. Like water from a waterfall finding its way on a beach toward the sea, it appears almost like an idyllic natural formation.

The source of the stream was a leak in the gate blocking the entrance of the spiral case. The engineer reassures me that the pressure of the river on the gate was tolerable, despite the gap that allowed some water to enter. The sound of water rushing through the bâche spirale of the G23 next door illustrated how powerful water really is. We proclaim our amazement as we stand there gazing at the vast expanse, magnified by the spectacular echo it creates. Francis sighs, “C’est beau, hein, la machine? C’est formidable!”

“Why was the first Pelamis scrapped and not displayed on a plinth?” he asked me. So here is a plinth, perhaps not quite the stone block with inscription that he imagined. On this plinth is Pelamis as a museum exhibit, although not quite Pelamis the machine: rather, Pelamis as a visual poem in memory and honor.

“Pelamis has been one of the icons

of the marine renewables industry.”

“The waves will keep pounding . . .

the world is still using fossil fuels . . .

we know marine energy will have its day.”

—Neil Kermode, European Marine Energy Centre, Orkney,

on the occasion of Pelamis Wave Power going into receivership.

This exhibit is her story;

she will live on in words,

long after the oil is gone;

future archaeologists will dive

for her, raise her up,

immortal, remembered,

“our sea snake” (they say, even now),

the first to make wave energy on the grid.

“Big projects bring big problems,” people say in the rural community of San Carlos, Colombia. Located at the convergence of six rivers, it was a logical place to build one of Colombia’s largest hydroelectric complexes. Moving the rivers shifted lines of power throughout the country and within the small community. Guerrillas made the mountainous region a base from which to threaten state power. Later, the paramilitaries and army came to fight the guerrillas; hundreds died in the worst years of war. Some 80 percent of residents fled. Those in urban exile dearly missed the quality of life they enjoyed at home, particularly lazy days spent fishing, cooking, cuddling, or camping at one of the many rivers or waterfalls. As the fighting lessened, thousands of people returned.

Several years ago, developers proposed a small hydroelectric complex that would destroy the community’s largest waterfall: the spectacular five-hundred-meter La Chorrera. Local organizers held protests. They blocked construction—for now. La Chorrera flows with the power of potential energy, one day perhaps to be channeled into lines that stretch to factories outside the city of Medellín to turn lights on in homes along the Caribbean coast. Untouched as of yet, it provides its own form of energy for local residents.

“It does my spirit good to live in this place,” the teacher said, as he showed me pictures of La Chorrera that he had taken at his farm. Love, too, is electric. It is a spark, a current connecting us to each other, to land, to life itself. La Chorrera’s potential courses down rocks where couples hide from gossipy neighbors. A retired teacher sits on his hammock feasting on the beauty of his home with a safety unimaginable ten years before—lovers of this land and life electric.