Our Electric Sustenance

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

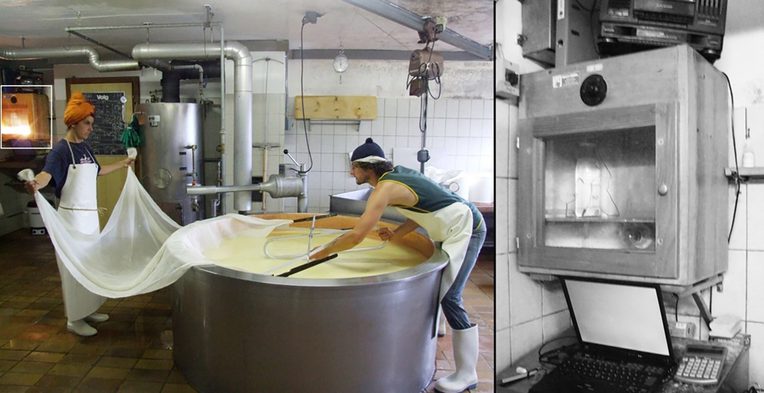

Only recently, I realized that I had never followed up on the incubator. In 2009, I worked as a cheesemaker at a cooperative alpine dairy in Switzerland. Once a week, one of the farmers drove up to deliver a packet with three small brown plastic bottles containing starter cultures. They arrived by mail from an agricultural research institution called ALP. Every day around noon, after the cheese was out of the vat and in molds, I would prepare my cultures for the next day by incubating freshly pasteurized milk with the starter cultures. They had names like MK-401.

Then I put the milk in the incubator, a wooden cabinet with a glass door. Inside, a thermometer stem in a bottle of water connected to a thermostat controlled a one-hundred-watt light bulb, keeping the temperature inside at a constant 40ºC. Although we were working at an altitude of nearly two thousand meters, the whole operation depended heavily on the grid: fences, the butter churn, agitators, and the milking system for 120 cows were all operated on grid electricity. But it was only much later that it occurred to me that the precondition for all of this—lively cultures of lactobacilli that keep the bad bugs in check and ferment the milk into cheese—was electricity that provided my cultures with the right environment to grow. I might have given them the milk sugar they needed to eat, but the light bulb provided the warmth they needed to maintain their appetite.

Toward the end of that summer the European Union announced that classic light bulbs would be outlawed. Swiss legislation would follow suit. The new energy-saving bulbs, I reasoned, would never have the strength to keep the cultures thriving. I told the farmers to stock up on old light bulbs, or get a different incubator. Now I wonder what they did.

Oh, kettle! You’re only an electrified pot.

You can’t play my favorite music, or tell me how my friend in Barcelona is feeling.

Covered in lime scale rather than liquid crystals, you don’t shine;

Stuck in the kitchen you are, really.

You’re such an old technology!

. . . But how to live without you? How?

In the British Isles, kettles are everywhere. In homes, workplaces, and community centers; wherever there are people, there are kettles. This technology is primarily associated with the activity of making tea. It is used by individuals to self-regulate their mood, thermal comfort, and flow of activity; it is used by groups, too, to create informal occasions for bonding.

A kettle is a device for boiling water that is said to be more efficient than other technologies, such as electric cookers. However, it does have a role in energy loss. This is because it is often filled with more water than is needed. A kettle is never empty. It keeps preboiled water for future consumption. Overfilling the kettle comes from thinking about the potential needs of the household: someone else might want a cup of tea in the immediate future, or warm water might be needed for cooking.

Alongside hot water, kettles produce steam. In the past, people sometimes boiled water when they didn’t need water but instead needed steam: to steam hats, for instance, or to seal envelopes. This was a rather energy-intensive approach. In thermodynamic terms, steam is energy loss—it is heat that is being lost through contact with cold air.

But steam is also

The breath of a dragon.

The boiling water is alive!

It’s crackling and bubbling

And fills the house with its birth.

On winter dawns, instead of sun—

I get a cup of tea.

I landed two hours ago, and tomorrow I start my five-year-long PhD journey. The agent arrives in the desolate parking lot with a V6 3.6-liter SUV. Ms. Garcia quickly tucks my damage deposit into her purse and then explains, without any sense of irony, that this wooden box covered in drywall, with thin windows, is my cozy, one-bedroom efficiency. It is hot inside but Ms. Garcia reassures me that “everything is bigger in Texas” and that my powerful AC will turn this anonymous refuge into a cool paradise in “just-a-sec.”

Look at all of my new luxuries! A walk-in-closet, a ceiling fan, the giant standard white refrigerator: what a commodious life surrounded by the electric devices and conveniences that North Americans must have! While the AC is kicking in, I even turn on all of the lights to feel more integrated.

Suddenly I notice that, in the kitchen, there is an electric switch but no appliance or light nearby: what is that for? I timidly turn it on: “GRRRRRRWHHH…” An infernal noise echoes from the sink. Instinctively I jump back, terrified. I have been living here for five minutes and I have already destroyed something. I call the management. When I tell Carlos, the maintenance guy, that a monster in the sink is activated by a switch on the wall, he bursts out laughing. Then he solemnly declares: “Here in America, my friend, people throw stuff in it and press the button: easy!”

I get it: peels and scraps are ground by an electric device and then vanish into the drain forever. I just hope that “garbage disposal” is not a local metaphor for the fate of scholars from distant lands.