Our Electric Transitions

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

I am standing on the top of CopenHill: a waste-to-energy incinerator under construction in Copenhagen. The power plant is eighty-five meters high and shaped like a mountain. It has been built by the Amager Resource Center and designed by the Bjarke Ingels Group. Its operators invite the public to ski down the building’s roof and mountain-climb up its sides.

While the spectacular images of this hybrid building have made their way around the world via media, it is—both literally and metaphorically—a burning platform! Here, conflicting visions about futures and sustainability collide and collapse. Is it sustainable to burn waste and turn it into energy and heat? Or would the €540 million have been better invested in waste reduction and recycling technologies? The debates are heated. The person at the visitor center describes the incinerator as a transition technology, telling me: “Until we have found a path to a wasteless society, we need this new and more sustainable incinerator.” In the building, I am thus standing on a waste- and steam-powered ship transporting us from a dirty past into a cleaner and greener future. For the time being, though, the Amager Resource Center actually imports waste from neighboring countries in order to keep the pot boiling.

Power plants and energy infrastructures have been made ever more invisible to the public; they have been turned into “second nature,” as Geoff Bowker (1995) puts it. With CopenHill, the Amager Resource Center wants to become part of the city by engaging the public in fun (second) nature activities. With his guiding design principle of hedonistic sustainability, Bjarke Ingels believes that architecture, though the making of “social infrastructures,” has the power to engage the public in sustainability and energy. It is not yet clear, though, how visible the waste incineration and its environmental footprint will be to the skiers and climbers.

My dad’s 2.5 kilowatt micro wind turbine is one of 639 grid-connected domestic wind turbines in Orkney, an archipelago off the northern coast of Scotland with the highest concentration of domestic turbines in the United Kingdom. One in ten Orkney residents make their own power; Dad uses his to charge an electric car and to run an air-to-air heating system. The Orkney Islands Council’s vision of Orkney’s electric future is becoming reality.

In 2016, Orkney generated 120.5 percent of its electricity needs, but the grid infrastructure was not designed to cope with renewable generation; the interconnector between the islands and the Scottish mainland is in danger of overheating.

Micro turbines, exporting a maximum of 3.6 kilowatts into the grid, do not endanger the interconnector; it is the larger, mainly-community owned turbines that get curtailed. When turbines stand idle, community members know they are losing the generation and feed-in tariff income vital to repay their investment and to fund community projects.

One answer is to increase local demand, but electricity is expensive. Islanders pay a two-pence-per-unit surcharge based on geography; 63 percent of Orkney households live in fuel poverty (the highest level in Scotland). A local charity is working with community turbines and householders to increase generation and reduce bills. Battery storage and hydrogen fuel cells offer exciting possibilities, but without tariff control, Orkney’s energy future is at the mercy of the market.

The grid connects and constrains; energy policy and regulation simultaneously reward and penalize generators; electricity is both abundant and unaffordable. Orkney’s electric future is being made through this entanglement of the technical, political, economic, and social. Its challenges are local, shaped by its particular geography, history, and socioeconomic circumstances. Yet they are also part of a global story about the relationship between energy and power in a time of environmental, economic and political change.

“Flatpack and modular: solar PV is the Ikea of energies,” I scribbled in the margins of my notebook. I was spending the afternoon in an unelectrified rice-growing village in southern Karnataka, observing the pilot test of a solar dehusking machine. Despite having spent months in the field studying solar electricity, it was the first time that I was encountering solar panels packed up. Deceptively simple in their light brown, flat cardboard boxes, they were propped against the wall of a farmer’s house. The incongruity of the setting only served to underline the association. Flatpack. Modular. The promise of democratic access.

If energies are design philosophies, then solar is the new energy minimalism, challenging the wasteful excess coded into the lavish, consumptive cornucopia that is carbon baroque. As raw material, carbon presides over the proliferation of plenitude. As energy source, carbon produces a plethora of particulate excess and leaks heat even as it is generated.

Sunlight, on the other hand, is without inherent chemical form. It is energy stripped to its basics: heat and light. Based on the capture and not the release of energy, its production is customized and precise. While carbon is owned by monopolies, solar’s modularity makes it uniquely accessible to both unelectrified Third World farmers and megawatted millionaires.

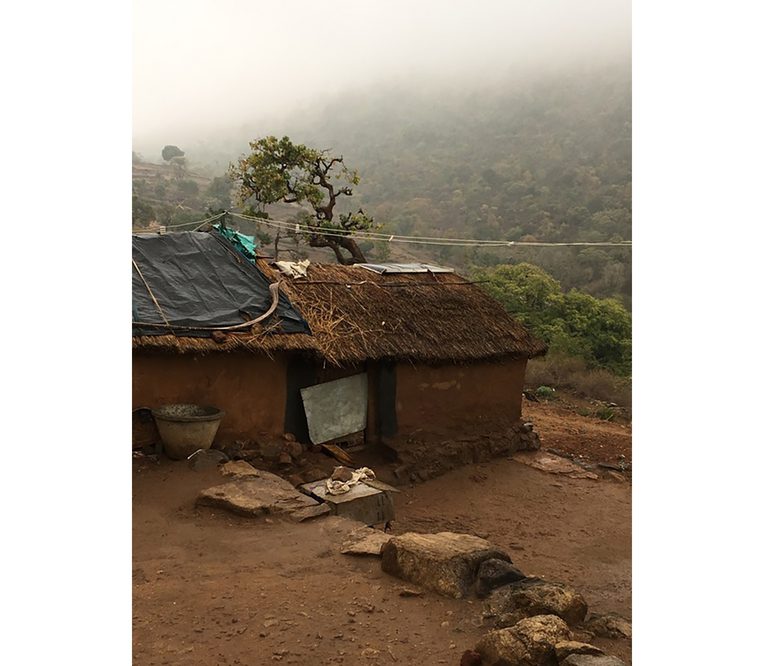

Yet panels, like Poängs, tend to be disposable. Beyond the feel-good, matte-finish catalogs of ready-to-assemble energies, Ikea’s brand of minimalism is mimicked in another way: in the Indian countryside, panels are frequently abandoned. Thatched rooftops are dotted with quiet disrepair as twenty-five-year warranties get truncated to three years of use. At times, silicon sheets curl up and strip off, exposing the carbon-fueled chemical kitsch that lies beneath. What design philosophies await us in the aftermath?

Bowker, Geoffrey C. 1995. “Second Nature Once Removed: Time, Space, and Representations.” Time and Society 4, no. 1: 47–66.