Participatory Media Research and Spain’s 15M Movement

From the Series: Occupy, Anthropology, and the 2011 Global Uprisings

From the Series: Occupy, Anthropology, and the 2011 Global Uprisings

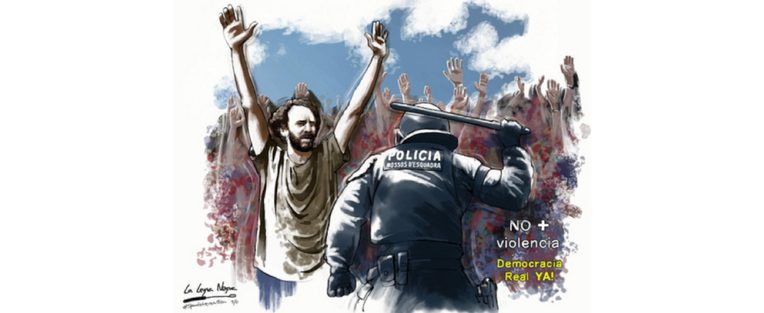

One striking feature of Spain’s 15M (or Indignados) movement has been the pervasive, sophisticated, and distributed use of social media by hackers, bloggers, lawyers, students, grassroots activists, and countless ordinary citizens. Although a few fundamentalist hackers refused to join corporate platforms such as Facebook or Twitter, most campaigners justified their use on pragmatic grounds. For example, when the Barcelona node of the umbrella platform Democracia Real Ya! (Real Democracy Now!, DRY) was created in March 2011, participants were encouraged to use both Facebook and a non-proprietary web forum to coordinate their activities. When it became apparent that Facebook was the preferred site, the group’s informal leaders readily went along with the majority.

Throughout my Barcelona fieldwork on the 15M movement, I took part in a range of collaborative activities across various online platforms. Two examples will illustrate this participatory approach. Both entail the use of digital media to copy, paste, share, and modify knowledge with fellow citizens, representing but a small subset of practices within a rapidly expanding participatory ecology. The first example concerns the use of Facebook to co-author political texts. As a native English and Spanish speaker, part of my modest contribution to the movement has been to act as an occasional translator and proof-reader. For instance, I once shared via Facebook what I thought was an improved version of a passage from the English translation of the DRY manifesto. In a matter of minutes, another user replied with what we both agreed was a better translation, which I duly forwarded to the manifesto team. This example may seem pedestrian, but it captures neatly the sorts of micro-political collaborations amongst strangers—including scholars—that social media enable on a much vaster scale than was possible even a few years ago, before the explosive uptake of social media platforms.

It is important, though, not to draw too sharp a distinction between corporate and "free" platforms, for skills and habits can migrate to open-source platforms—and back again. My second example demonstrates this transfer. As we were nearing the May 15 deadline—the date when protest marches were due to take place across Spain—I learned about a new site created to share information about local groups that may lend support to the protests. Having painstakingly drawn up a directory of local groups on my research blog, I was happy to contribute to the collective effort. Soon I was interacting with eight to ten other people—all but one of them strangers—by means of an open-source platform developed by Sweden’s Pirate Party, which advocates greater Internet freedom. The platform is aptly named PiratePad. It consists of a main wiki area where users can easily co-author public texts and a right-hand column with a chat facility. On entering the pad each user must choose a color through which their particular inputs can be identified. The chat area allows for real-time discussion of the materials as they are being shared and modified. Having spent months slowly building up a directory on my blog, I marvelled at the extraordinary speed, smoothness, and efficiency of this group exercise. By pooling our individual knowledge, in less than two hours we had produced a comprehensive list of groups.

These sessions were also instructive regarding the mechanics of informal leadership in the early days of the movement. Although 15M supporters have always insisted that the movement is "horizontal" and leaderless, as in all human ventures some individuals are, of course, more influential than others. But they must exercise their power subtly, leading by example not command. Like longhouse headmen among the egalitarian Iban of Sarawak with whom I lived in the late 1990s (Postill 2006), 15M leaders govern through "a subtle mixture of persuasion and admonition (Freeman 1970: 113)."

Thus when I copied and pasted a link to a small political party from my blog onto the pad I was challenged by an informal leader through the open chat. She cordially pointed out that in keeping with the grassroots nature of the fledgling movement we should not include political parties or trade unions in the directory, only citizens’ groups. I promptly deleted the offending entry.

As it happens, it linked to Catalonia’s Pirate Party.

--This essay is adapted from a passage in Postill, John. 2012. "Digital Politics and Political Engagement." In Digital Anthropology, edited by Heather Horst and Daniel Miller Oxford: Berg.

Freeman, J.D. 1970. Report on the Iban of Sarawak. Kuching: Government Printing Office, reprinted as Report on the Iban, London: Athlone Press.

Postill, J. 2006. Media and Nation Building: How the Iban Became Malaysian. Oxford and New York: Berghahn.

John Postill is Senior Lecturer in Media at Sheffield Hallam University and a Fellow of the Digital Anthropology Program, University College London. He is the author of Media and Nation Building (2006) and Localizing the Internet (2011) and the co-editor of Theorising Media and Practice (2010), all three published by Berghahn.