Peatland Substitutions: From Wastelands to Treasure Troves

From the Series: Substitution

From the Series: Substitution

The International Peatland Society defines peatlands as terrestrial wetland ecosystems in which waterlogged conditions prevent organic, carbon-rich plant material from fully decomposing. As such, pristine peatlands provide important “ecosystem services,” functioning as water catchment areas, coastal buffers, and most significantly for the climate, important carbon sinks.

Malaysia is home to 6 percent of the world’s tropical peatlands by area (2.8 million hectares), and 12 percent by magnitude of the peat carbon pool. However, 60–66 percent of this area has been converted to managed land cover types. This process kick-starts decomposition which releases carbon into the atmosphere, effectively substituting the function of these peatlands from that of carbon “sinks” to carbon “sources.”

This essay explains how metaphors played a particularly important role in carrying over legacies of colonial thought and practice related to land use substitution in Malaysia, as one metaphor (the wasteland) is substituted for another (the gold mine).

Malaysia was colonized by the British until 1957. During this time, the colonial administration viewed seemingly untouched tropical environments as “wastelands”; barren, overgrown, and/or desolate areas of wasted potential. Motivated by the noble cause of realizing this heretofore wasted potential, the colonial project commenced to substitute these “wastelands” with productive crops of tapioca, coffee, and rubber.

Following in the footsteps of their colonial masters, post-independence Malaysian leaders embraced the modernization theories of the 1950s and 1960s that emphasized the built (or in this case, intensely cultivated) environment over the “natural” environment. They conceived of plantations and mines as “modern” sectors that were the end-point of development. Pristine frontier areas continued to be seen as ‘wasted’ unless they could be converted into plantations or mines, through which they could, finally, acquire some value.

In 2015, Malaysia’s communication to the United Nations stated that “in the 1960s and 70s, peatlands were considered a wasteland and draining was considered an effective rehabilitation to improve the productivity.” However, difficult working conditions, low agricultural potential, and sufficient availability of mineral soils meant that peatlands were largely untouched.

This changed in the 1980s, alongside the region’s palm oil boom. Low demand for latex following the invention of synthetic rubber encouraged rubber plantations to shift over to oil palm which was doing well in neighboring Indonesia. After most rubber plantations were converted, more land was needed. Agricultural knowledge that oil palms are naturally able to withstand waterlogged peatlands, supported by deep-seated belief that pristine peatland equates to wasteland, justified the substitution of pristine peatlands for oil palm cultivation.

Hence, with interventionist hydro-management and drainage, large swathes of pristine Malaysian peatlands were substituted with oil palm plantations. Today, oil palm plantations are the main type of managed land cover (73 percent) in converted peatlands in Malaysia, with the rest being pulpwood plantations (26 percent). Malaysia is the second largest producer of palm oil, with the second largest area of oil palm plantations, after Indonesia.

The “wasteland to gold mine” metaphor is taken a step further in the East Malaysian state of Sarawak, which is home to 57 percent of Malaysia’s peatlands. Here, various Sarawakian leaders and regional newspapers have described peatlands as the state’s potential “gold mine,” epitomizing the enduring appeal of peatlands as ripe for conversion from wastelands into sites of economic prosperity. Of course, “gold” itself hearkens back to legacies of colonial accumulation and early capital. By 2015, 50 percent of Sarawak’s pristine peatlands have been substituted with industrial plantations.

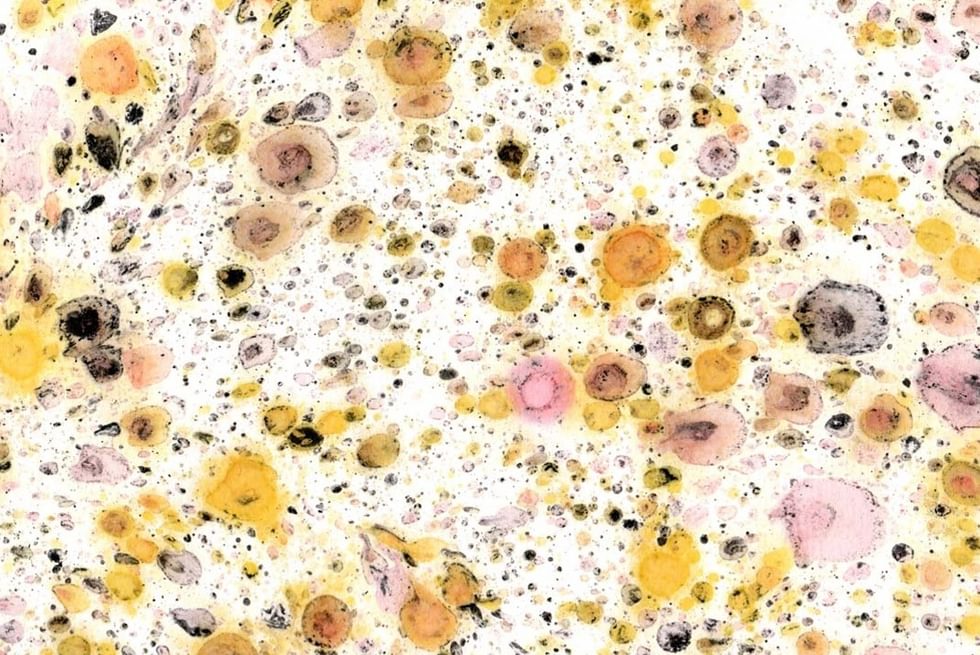

The “gold mine” metaphor however has been put to work in many different ways. Various Malaysian media outlets have reclaimed the meaning of this metaphor by using “black gold” and “treasure’” to describe the value of peatlands not in its substitution, conversion, or extraction, but inherently for what it already contains—as a site of “many treasures” and “really a kind of living museum.” In such writings, adjectives such as “beautiful,” “majestic,” and “amazing” are used to describe peatlands and their intrinsic value and/or future value—even though the dark, damp, and dangerous peatlands may not necessarily match the aesthetic expectations of majestic forests.

Returning to the role of peatlands as a provider of ecosystem services, the concept of Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) was originally conceived in the 1980s as a metaphor for the use-value of nature. This ties in closely with current debates about the value of carbon and the potential for the sustainable commodification of peatlands in the context of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) climate governance strategies.

Malaysia’s relies heavily on Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) removals to meet its global climate commitments. In support of this, Malaysia announced its commitment in 2021 to cap total oil palm planted area to 6.5 million hectares, from the reported 5.8 million hectares planted in 2018. While this is promising, without targeted interventions to provide a buffer against intensifying development pressures, pristine peatlands are unlikely to continue to serve as carbon sinks for long. A sea change is required so that this so-called “black gold” might be understood as valuable only when kept locked away in deep peat “treasure chests.”

Just as in the past, metaphors may be a powerful tool to justify this new form of substitution for a more secure climate future. However, substitution merely in terms of the structure of metaphors (the idea of “treasure trove” supplanting “gold mine”) raises the question as to whether these ideas are really all that different—how meaningful is such substitution if peatlands’ place in the commodity markets is merely substituted with monetization in markets for carbon credits? Such substitution maintains the economic logic that peatlands must produce some kind of revenue, and are not “intrinsically” valuable in and of themselves, continuing value regimes that remain centered around land commodification.