Planeterra Nullius: Science Fiction Writing and the Ethnographic Imagination

From the Series: Speculative Anthropologies

From the Series: Speculative Anthropologies

They are back, and this time they are here to stay.

It’s Tuesday and I am running predictably behind. I click accept, paying three thousand credits as I shift into the express skyway.

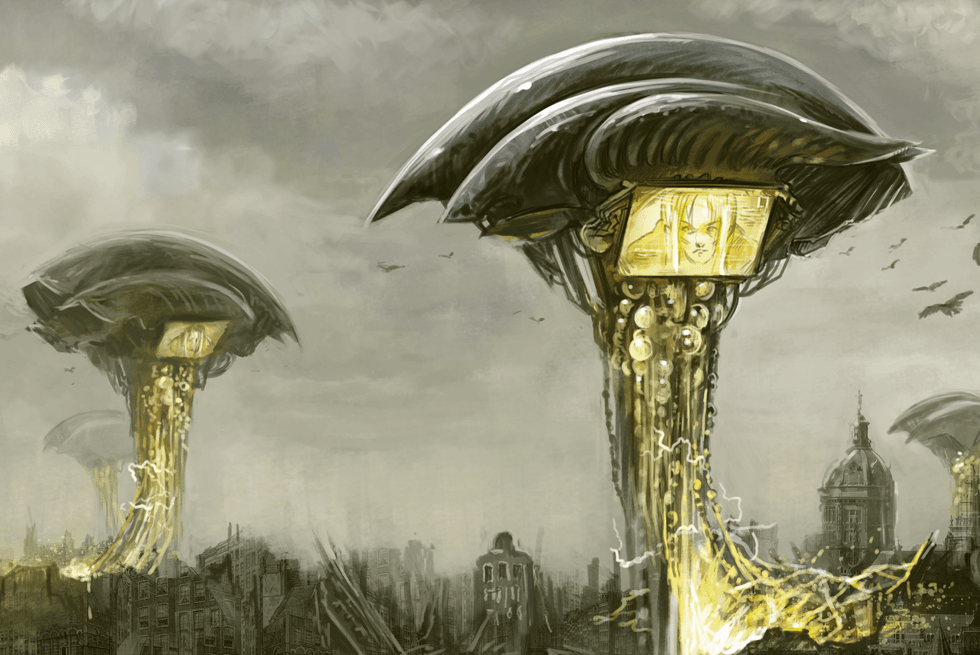

It’s then that I first hear it—that sickening low drone slowly overtaking the cacophony of the Sydney rush hour. Traffic slows, then stops. The 100° morning air rushes in as I release the top hatch, squinting skyward toward the trapezoidal silhouettes.

As nine shadows spread across the metropolis, my pupils dilate to take in the spacecraft. Reassembling into a single tessellation, they settle into an inlet just south of the city.

Never had there been so many.

The first contacts were brief and shrouded in mystery. For hundreds of years, there have been glimpses of the Snaeporue, who most simply referred to as the “Blues.”

Rumors from the north of vague shapes on the horizon, sapphire skin, and strange weapons: 2206 in Cape York, again in 2223. Whispers from the west at the end of the twenty-third century.

I was a child when their first spaceship visited Sydney, eighteen short years ago. We approached with hope. It ended badly. Their quickness to anger, the bright flashes, the carnage. They took our weapons and as quickly as they arrived, they were gone.

My parents said the Blues wouldn’t return and not to worry. I tried not to, until the blue skin sickness overcame them both.

My fingernails dig into my palm as the memories come rushing back, the cocktail of scarlet and salt trickling from Mom’s pale eyes over cerulean-spotted cheeks.

She was wrong.

They are back, and this time they are here to stay.

It’s nearly 2 a.m. when I look up from the datapad of my many-great-grandfather’s journal in the digital archives at the Institute for Egavas Studies in Canberra. After years of study, I am reading in the original English, and I can feel his voice reverberating through my bones. I collect myself, momentarily overwhelmed by how much is left out of our official histories.

I saturate my lungs with air and blood with caffeine, then continue:

Over a thousand Blues moor above the southern bay. We fight back as part of the new Pan-Earth Alliance, comprised of hundreds of nations. We kill some of them as they take out waves of our troops and abduct our emissaries.

Days blur together as Sydney descends into chaos. A new wave of skin sickness claims billions worldwide, while the Blues spread and more spaceships arrive.

Most of our diplomats never return, but the ones who do speak of a planet called Eporue, where they mastered the Blues’ Hsilgne language and met Emperor Egroeg.

We learn that the Blues view us as lesser beings and call us Egavas. Their society runs on the very magma that courses through our planet. Since we do not harvest the liquid rock, they have claimed Earth as theirs through a distortion of intergalactic law, declaring it Planeterra Nullius, or “nobody’s planet.”

Traveling by night, we organize resistance movements and move toward the desert.

I read for hours, moving from this journal to others, eager to hear the voices of my ancestors and absorb their knowledge. Endless pages of massacres, disease, and stolen children give way to myriad moments of courage and triumph.

Against all odds, Planeterra Nullius was overturned in Snaeporuen court only a couple of decades ago, leading to the Egavas Title Act through which I, along with other Earth descendants, helped to secure rights in and around Sydney.

Despite hundreds of years of struggle, we not only survived, but are growing in strength and numbers. No one can deny that we are actively fighting to determine our futures on Earth. Now even many Blues support a centuries-overdue treaty with Earthlings.

My eyes move from screen to window as the sun edges over the horizon, bathing cavernous shadows in the light of dawn.

This short science-fiction story is set exactly six hundred years after Captain Cook’s infamous landing in Botany Bay, which marked the beginning of Aboriginal dispossession. The story inverts the history of Australian colonization, with extraterrestrials invading and settling Earth. I engage parallel events from initial colonial contact through current Indigenous political movements, as well as instances of dehumanization, pandemic disease, and postapocalyptic hope. Inspired by Horace Miner’s (1956) articulation of the Nacirema, I utilize the technique of backward spelling to help students denaturalize anthropological representations of the Other. This exercise in empathy is aimed at encouraging non-Indigenous students to attempt (with great humility) to imagine what it might feel like to experience colonization and subsequent intergenerational trauma.

I draw on the rich history of anthropologists engaging science fiction (Stover 1973; Collins 2003), as well as the innovative writing of authors such as Ursula Le Guin and Octavia Butler. As a genre that lends itself toward subversive critique, science fiction at its most socially incisive has often been crafted by women and people of color and has been central to the development of feminist, Afro, and Indigenous futurisms. These critical literatures engage the ways in which dominant imaginaries project gendered, racialized, and colonial tropes into and onto the future, while also highlighting alternative visions. Indigenous futurisms scholarship (see Dillon 2012) holds particular promise for reimagining enduring tendencies to slot Indigenous people into mythic pasts and suffering presents. Such work carries the radical potential to expand the limits of the ethnographic imagination. Thus, it is essential that anthropologists continue to engage, amplify, and produce science fiction.

Collins, Samuel Gerald. 2003. “Sail On! Sail On! Anthropology, Science Fiction, and the Enticing Future.” Science Fiction Studies 30, no. 2: 180–98.

Dillon, Grace L. 2012. Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Miner, Horace. 1956. “Body Ritual among the Nacirema.” American Anthropologist 58, no. 3: 503–507.

Stover, Leon E. 1973. “Anthropology and Science Fiction.” Current Anthropology 14, no. 4: 471–74.