Politics as Volkation

From the Series: The Rise of Trumpism

From the Series: The Rise of Trumpism

I teach Max Weber’s “Politics as a Vocation” essay in a course on classical sociological theory at John Jay College in New York. During a recent discussion of the essay, students took issue with the many ways in which Donald Trump’s business interests will ultimately benefit from his presidency. What students implicitly grasped is that this is not the way politics is supposed to work. As a scholar of populism, I recognized in my students’ discontent a truth of politics acknowledged by democratic theorists, but which is today coming into new focus. As we watch Trump’s Cabinet fill up, there is no longer any question that “the leadership of a state or party by men who . . . live exclusively for politics and not off politics means necessarily a ‘plutocratic’ recruitment of the leading political strata” (Weber 1998, 85–86).

Anyone who says that nothing like Trumpism has ever happened is both right and wrong. Trump’s rise to power is the latest example of a global phenomenon, in which problems occurring within the relationship between democracy and capitalism eventually lead to populism—just as the historical structures of democracy and capitalism themselves were forged out of great populist revolutions of the past, from Solon to Spartacus and Emmanuel Sieyès to the période française.

Populism operates as the unconscious symbolic structure of the political. It takes many forms on a spectrum that ranges from discursive elements to active mobilizations. It draws crucial energy from the way that groups form in partially structured ways around those who constitute the inside and outside of the group: e.g., us/them, friend/enemy, and most notably people/power. For Ernesto Laclau (2005, 74), populism is a discourse that separates the people from power and mobilizes the latter through the “unification” of their democratic demands.

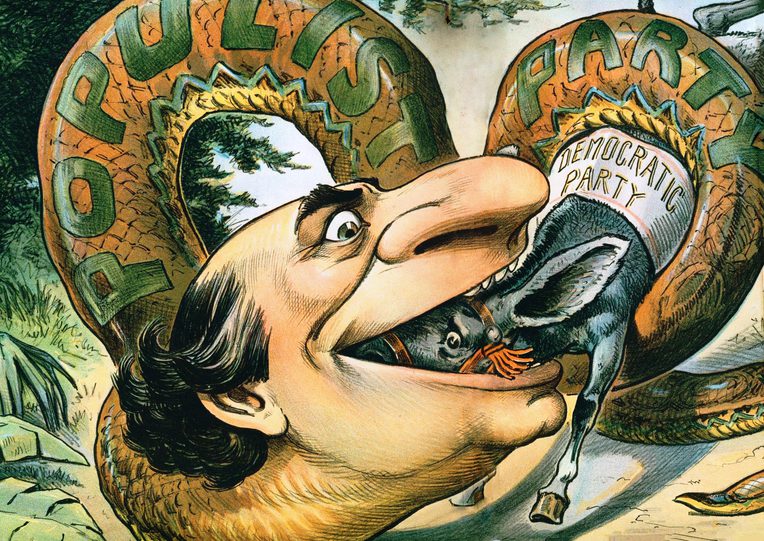

The first cases labeled populist by scholars (mostly political scientists and historians) were the mid-nineteenth-century Russian Narodnichestvo (intellectuals exalting peasant values) and the U.S. Peoples’ Party of the 1890s (Southern farmers reacting to hardships and connected to big business and the elite). Subsequent cases labeled as populist follow different trajectories in different regions. The majority of scholarship focuses on Latin America, the United States, and Europe, although there are emerging bodies of literature on Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, too.

What, then, does Trump have in common with Latin American populism? Rather than starting in Greece or France, we could just as easily begin in a journey from Benito Mussolini’s Italy to Juan Perón’s Argentina. Populism emerged from processes of modernization that blended elements of authoritarianism and democracy, instead of formal institutional structures. The classic image of the mid-twentieth-century populist leader playing on the trope of the caudillo—delivering speeches and dispensing favors, forming multiclass coalitions, mobilizing large unincorporated groups, employing import-substitution industrialization, tarrying with fascist elements—resonates once again.

Prior to the advent of Trumpism, however, scholars did not associate U.S. populism with the dilemmas of modernization in Latin America, but rather with a rich tradition of anti-elitist and sometimes conspiratorial rhetoric—what Richard Hofstadter famously called “the paranoid style in American politics." If we compare Trump to other U.S. politicians who were labeled populist in the past, we might say that he has Father Coughlin’s fascism, Joseph McCarthy’s impulsivity and penchant for conspiracy, and Ross Perot’s model of government as a profitable business.

Although aspects of nationalism, isolationism, and xenophobia have always been present in the tradition of U.S. populist rhetoric, Trumpism stands to turn these discursive elements into policy and practice in a way reminiscent of right-wing populist parties in Europe. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders has a similar haircut and stance on Muslims, just as Silvio Berlusconi is another business-clad phallus-trickster of the orange persuasion. Simultaneously across Europe and South America during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the marriage between populism and neoliberalism was sealed. Peru’s Alberto Fujimori in Peru comes to mind as a comparable sort of white-collar criminal man of the people, with his corporate politics of anti-politics.

What, then, is new about Trumpism? For one, we have a president-elect as an empirical type blending all three regional definitions of populism. With a strong appeal to the (white) people in the best U.S. tradition of rhetoric and a European-style anti-immigrant stance, Trump has mobilized large unincorporated sectors (the Rust Belt) and formed a (white) multiclass coalition. (Not to mention that, much like Perón, he has been granted an ism.) Populists in power are known for their centralized and personalistic forms of charismatic leadership. With control of all three branches of governments and most of the state legislatures of the greatest superpower in the world, this man, who embodies all of the worst blunders of right and left populisms combined, should surely not disappoint.

Riding in on a wave of discontent like Brexit, Trumpism is the protest of white isolationism. But whereas protests function as vanishing mediators, Trump as mediator won’t vanish. Instead, his spectacular Cabinet promises to dismantle itself in surrender to the states.

To be sure, many—including Vladimir Putin, Rafael Correa, and Slavoj Žižek—wanted Americans to vote for Trump in order to bring about a perverse Trotskyite fantasy of destabilizing U.S. empire and global capitalism. However, with Exxon at the helm of the State Department and executives from Goldman Sachs and Silicon Valley venture-capital firms in Cabinet positions, all government institutions whose responsibilities come into conflict with capital are on the butcher’s block, from environmental regulation to public health. It seems that business and politics are more seamlessly in sync than during the Eisenhower and Reagan administrations combined.

This merger between the Trump Organization and the U.S. government exemplifies everything that Weber warned us against, with a clash of civilizations as the cherry on top. Scholars have long argued that the conditions of capitalism are eroding our democratic institutions and that capitalism can only perpetuate itself and the levels of social inequality it generates through more forms of authoritarianism. What they could not have foreseen is the reemergence of authoritarianism in the name of the people.

Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. New York: Verso.

Weber, Max. 1998. “Politics as a Vocation.” In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, translated and edited by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, 77–128. New York: Routledge. Originally published in 1919.