Post-Conflict Urbanism and The Logics of Warfare In Colombia

From the Series: The Colombian Peace Process: A Possibility in Spite of Itself

From the Series: The Colombian Peace Process: A Possibility in Spite of Itself

During the ongoing peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the urban areas have been perhaps the most conspicuous omission. The focus on issues such as the creation of Autonomous Zones for Peasants (Zonas de Reserva Campesina) and the substitution of coca crops is a reflection of the rural emphasis that continues to pervade understandings of the Colombian conflict and the much-anticipated post-conflict. While such issues are indeed central to any prospect of ending the country’s fifty-year conflict, they do not address the urban dimension of Colombia’s history of violence and inequality. In a country where more than eighty percent of citizens reside in cities and where urbanization has been closely entangled with the dynamics of the armed conflict, imaginations of the post-conflict cannot afford to neglect urban life.

As in Raymond Williams’s (1973) classic analysis of the interdependence of the country and the city, the line dividing Colombia’s rural conflict and urban realities is porous. The explosion of violence in the countryside in the 1950s was partly an expression of the struggles among urban elites and their loss of territorial control in the hinterland. Significantly, the symbolic event that marked the beginning of La Violencia (the country’s most intense period of bipartisan violence, from 1948 to 1958) was an urban conflagration known as El Bogotazo: the assassination of populist presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitan in Bogotá on April 9, 1948, and the ensuing urban riots that destroyed a considerable part of the capital’s historic center and that rippled across midsize cities and small towns throughout the country. From this perspective, the Colombian conflict—and perhaps particularly the post-conflict—calls for understandings that move beyond the binaries of urban-rural and center-periphery.

The logic of warfare has infused the production of urban space in Colombia for decades. In the city, the struggle over land that is at the heart of the country’s conflict is translated into a fight for urban property and projects of political and socio-economic control. The modes of regulation exercised by armed actors in the countryside are reproduced in spaces ranging from marginal barrios and red-light districts to wholesale food markets, informal commercial centers, and citywide economic activities (such as transportation systems or street vending). Illegal systems of taxation, policing, and coercion have been covertly deployed by guerrilla militias, paramilitary bands, and criminal organizations, typically with the complicity of state authorities and local political networks. These forms of urban governance are not merely reverberations of the armed conflict, but rather crucial nodes in the war’s networked geography.

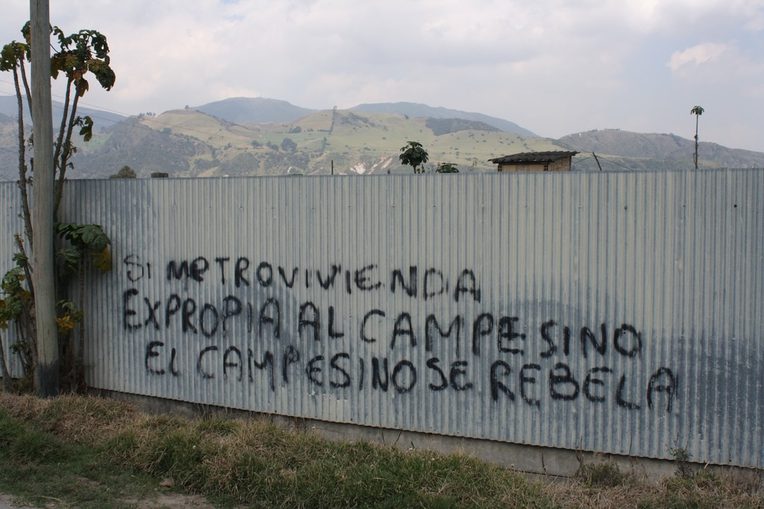

The urban dimension of the logic of warfare also extends to cities’ official technologies of governance (see Graham 2011). For decades, urban planning has covertly contributed to the class warfare and spatial segregation in cities across the country. From the modernist destruction of peasant markets and tenements to contemporary public space and urban revitalization policies, planning emerges as a technocratic mode of warfare, encoded in expert diagnostics and administrative procedures. As a property owner put it in the midst of a recent plan to redevelop a district in downtown Bogotá, “in the countryside they displace with guns, here they do it with decrees.” An equally suggestive illustration of the violence of bureaucracy was captured in graffiti in a semi-rural area in Bogotá. In response to the city’s plans to acquire land and develop affordable housing, the graffiti read, “If Metrovivienda [the city’s housing agency] expropriates the peasant, the peasant will revolt.” For impoverished residents, evictions and urban development followed the same rationale of state-sanctioned and paramilitary-enforced land grabbing for the creation of agro-industrial complexes in the countryside.

The uncertainties of the post-conflict are not limited to what will happen in the country’s violence-ridden peripheries. The reinvention of Colombian democracy and citizenship must move beyond the rural-urban divide that continues to shape the spatial imagination of the conflict. This includes addressing the obvious yet intractable difficulties that demobilized combatants and displaced persons face when they are “reinserted” into starkly unequal and violent cities. But more fundamentally, it entails excising the widespread practices—from the misrule of law and political corruption to the expansion of criminal economies—that support and reproduce the logics of warfare in cities. Such rationalities are inherent to rural systems of order and governance, as much as they are installed in the core of the state and of urban Colombia.

Graham, Stephen. 2011. Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism. London: Verso.

Williams, Raymond. 1973. The Country and the City. New York: Oxford University Press.