This post builds on the research article “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States,” which was published in the February 2008 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published several essays on food and the politics of food. See, for example, Benjamin Orlove’s (1997) article on food riots in Santiago, Chile, "Meat and Strength: the Moral Economy of a Chilean Food Riot", Mark Liechty’s (2005) "Carnal Economies: The Commodification of Food and Sex in Kathmandu", or Judith Farquhar’s "Eating Chinese Medicine" (1994) on the intersection of food and health.

Scientific culture and science in action have also been important sites of inquiry in Cultural Anthropology. Of particular relevance are Karen-Sue Taussig’s "Bovine Abominations: Genetic Culture and Politics in the Netherlands" (2004) and Sarah Pinto’s "Development without Institutions: Ersatz Medicine and the Politics of Everyday Life in Rural North India" (2004).

Interview with Heather Paxson

EL: Would you relate your previous research into motherhood and reproduction to your artisanal-cheese research at all?

Heather Paxson: Both projects explore arenas where people confront and even welcome ethical questions in their everyday lives and where they struggle to negotiate as sense of moral personhood.

EL: If ‘terroir’ exists in France as a concept that links taste and place, how does that term compare to ways in which American artisanal cheese farmers discuss place? Why could that term not apply to industrially produced cheeses?

HP: Well, I’ve written an article about this very question (Fall 2010 American Anthropologist). Here’s a short answer: in France, terroir is a concept that links people and place through narrative reference to a collective agrarian past; in the U.S., where innovation trumps tradition as a source of value, terroir is future-oriented. American artisan cheesemakers are working to reverse-engineer terroir as a set of relationships between land, landscape, animals, artisan practice, and cheese as a means of revitalizing rural ecologies and economies and (re)making place. In the U.S., terroir is prescriptive rather than descriptive.

Industrially produced cheese can arguably create place, too, by providing jobs and the basis of a regional identity, say, but this is a different sort of place-making. Terroir talk calls attention to the productive agencies of pastureland, dairy animals, and even microorganisms in helping to create cheese whose flavor profile might be said to reflect and thus represent the place of manufacture: this is a large part of how terror discourse makes “place.” Terroir is all about distinctiveness and distinction. Industrial cheese fabrication, in contrast, is predicated upon removing ‘place’ from the milk that becomes cheese through standardization, homogenization, and pasteurization. Standardized placelessness is the goal of industrial fabrication, which is quite at odds with the very idea of terroir.

EL: How do the terms and ideas of ‘germ’ and ‘micro-organism’ work for the different groups and sub-groups of people involved in this discourse?

HP: Colloquially, germ is a pejorative term for a pathogenic microorganism.

EL: What expert roles are part of this type of cheese making? What expert (and inexpert) roles might part of industrial cheese making? Is the expertise located somewhere different?

HP: That question is too large to answer simply. In both sites, expertise is multiple and multiply located; these overlap some but by no means completely.

Editorial Overview

For the growing number of its U.S. producers and consumers, raw milk cheese is a traditional food processed safely by the action of good microorganisms in milk proteins; for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) it is a potential biohazard riddled with bad germs. Heather Paxson draws out the cultural, economic, and political stakes of artisanal cheeses in a February 2008 essay in Cultural Anthropology, “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw Milk Cheese in the United States,” underscoring the idea that dissent over how to live with microorganisms reflects disagreements about how humans ought to live with one another.

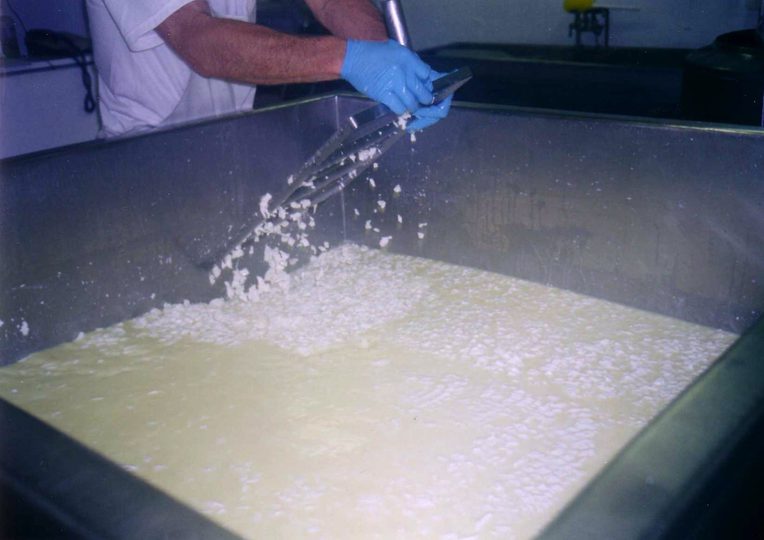

Paxon’s essay examine the gustatory and nutritional value, safety and political dimensions of raw milk cheese production, regulation and consumption in the United States, extending commodity network analyses in agro-food studies beyond global-local studies into the body and its gastrointestinal system. Drawing on interviews, policy analysis and participant-labor on a Vermont farm where raw milk cheese is made, Paxson describes how raw cheese aficionados think about the microbial agents at the heart of raw milk cheese, and negotiate “Pasteurian (hygienic) and post-Pasteurian (probiotic) attitudes. To support her analysis, Paxson coins the term ‘microbiopolitics’, after Foucault’s ‘biopolitics’, to draw out what microscopic biological agents mean, within food ethics and governance in particular, and for cultural analysis.

In a refreshing style, Paxson interleaves a step-by-step account of cheese production with “exegeses of key microbiopolitical moments” in the coming into being of raw milk cheese. Taking up the case of pregnant women, for example, she extends feminist critiques of the medical moralization of pregnancy to explore how raw milk cheese figures in American risk culture. The framework that Paxson uses for her analysis – revolving around “microbiopolitics” – convincingly demonstrates what cultural analysis misses when it neglects the microbial, and how what it means to be human is worked out alongside companions species on whose interactions we depend.