This post builds on the research article “Pressure: The PoliTechnics of Water Supply in Mumbai,” which was published in the November 2011 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published numerous articles on citizenship in India, including Francis Cody’s “Inscribing Subjects to Citizenship: Petitions, Literacy Activism, and the Performativity of Signature in Rural Tamil India” (2009); Aradhana Sharma’s “Crossbreeding Institutions, Breeding Struggle: Women’s Empowerment, Neoliberal Governmentality, and State (Re)Formation in India” (2006); and Ritty Lukose’s “Empty Citizenship: Protesting Politics in the Era of Globalization” (2005).

Cultural Anthropology has also published articles on the politics of urban poverty. See, for example, Clara Han’s “Symptoms of Another Life: Time, Possibility, and Domestic Relations in Chile’s Credit Economy” (2011); Jonathan Bach’s “They Come in Peasants and Leave Citizens: Urban Villages and the Making of Shenzhen, China” (2010); Danny Hoffman’s “The City as Barracks: Freetown, Monrovia, and the Organization of Violence in Postcolonial African Cities” (2007); and Deborah A. Thomas’s “Democratizing Dance: Institutional Transformation and Hegemonic Re-Ordering in Postcolonial Jamaica” (2002).

Interview with Nikhil Anand

It is interesting to understand how people come to do the research that they do, to understand what inspired them to pursue certain issues over others. How did you come to focus on this topic? Did you go into the field knowing the direction your research would take or did this focus emerge in response to conditions in the field? How was your presence understood in the field?

I came to Anthropology with a training in political ecology, and with a desire to study the formation and practice of environmental expertise. Initially I thought I might study biodiversity, but biodiversity’s experts and subjects often lived and worked at some distance from each other. Urban water was promising, in part because in cities like Mumbai, the governed and government officials, the very rich and very poor, all live in close proximity to each other. I came to be interested in how their relationships were made and maintained through everyday demands and experiences around the water network.

Another reason I was interested in studying urban water came out of a certain restlessness with narratives of (and against) neoliberal restructuring, and privatization in particular. In making the case against water privatization, I found urban activists (and scholars) to be glossing over the fact that the public system also had rules against providing water to marginal populations; that it also reproduced inequality. I found the exclusions of public systems interesting because, paradoxically, this fact did not preclude settlers in Mumbai from vigorously defending the public system. So I took this question to the field: Why do settlers defend a public system that also marginalizes them? And what does this say about the way in which cities (and their public systems) work?

I arrived in Mumbai in the midst of a large privatization debate that was taking place in the city. The World Bank had appointed consultants to recommend the privatization of water distribution in one part of the city. Different groups understood my presence in the city differently. Activists who I had worked with previously quickly welcomed my arrival, and sought to enlist my help in organizing the opposition to the project. Some politicians and settlers thought I was one of the Bank’s consultants. City engineers were altogether puzzled as to why an anthropologist was trying to understand an engineering system. Even after we became friends, they continued to wonder what I was doing there.

How do the pipes and pumps figure in the making of place in Premnagar? Do they configure the landscape in certain ways that signal the presence or absence of the State? How are legality and illegality construed in this context?

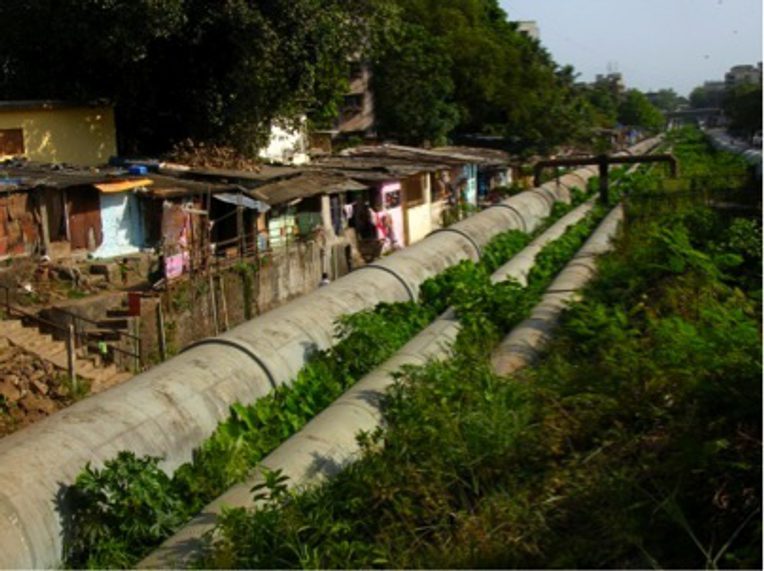

That’s a great question! While doing fieldwork, I was struck by how often the visibility and temporality of infrastructure networks was an index of a settlement’s vulnerability. Just across the street, in the neighbouring settlement of Meghwadi, water pipes are underground, emerging from the earth just long enough to feed shared taps. Their relative permanence and invisibility describe not only the reliability with which Meghwadi’s residents get water, but also the ways in which they are recognized as citizens of the city.

In Premnagar, many pipes (both legal or illegal) frequently run above the ground, and as such as more liable to breakage or leakage. Many households’ water infrastructure in Premnagar is quickly assembled at water time. Pumps connect private plastic pipes to the steel pipes of the city, drawing its water into the homes of its residents. The materials and practices of this temporary assemblage suggest a precariousness connecting to state services that the settlers in Meghwadi were just not subject to.

The state is very present in Mumbai’s settlements. Instantiating a very material relationship with the state, residents in most every settlement draw water from city pipes, or buy water from others who do. Yet, settlements are differentiated by the amount of work and capital they need to expend to connect to state services. In Premnagar, people had to invest significant capital, labour and time in getting water, in part because of the city water department’s unwillingness to extend and expand its infrastructure in the settlement. Oftentimes, because of this unwillingness, residents in the settlement found it easier and necessary to make their own arrangements, to draw water from city pipes without the authorization of the water department. The prevalence of these (illegal) connections were well known to city water department engineers, who often chose to act by not acting to disconnect them. Their present-absence in the area allowed the settlement to get state water without burdening state officials with the responsibility of having to manage and maintain these connections.

The analytic you utilize in the article is that of ‘pressure’ based both on the materiality of water and the social and political relations in Mumbai, where the loss of water pressure results from and contributes to loss of political pressure. Are there other analytic concepts that suggests themselves when talking about water in urban spaces?

I have been thinking about leakage these past few years as well, particularly in relation to Foucauldian approaches that attend to the importance of knowledge in the production of state power. Much of Mumbai’s water quietly leaks away after it is brought to the city. In and of itself, leakage is not unusual. It is characteristic of every urban water system including the systems in New York and London. What I am interested in here is thinking about how and why the Mumbai’s water department is rendered unable to know just how much water is leaking. I am thinking through how ignorance of this leakage works to make a particular kind of hydraulic state in the city.

You understand modern cities as ‘multi-layered’ that cannot be capture within the narrative of democratic liberal states, citizenship, or civil society. You also speak of ‘infrapolitics’, Scott’s notion in which daily acts of struggle are for the most part invisible and circumspect. So does infrapolitics become the primary mode of engaging the State in places like Premnagar or would they prefer to become part of a ‘deserving political society’? Does this apply to every instance of their interactions with the State (both as individuals and as a collective)? Are there disagreements within the community as to how government actors should be engaged at different levels? What do you see as happening to a settlement like Premnagar in the near future?

I have found Scott’s articulation of ‘infrapolitics’ to be helpful in thinking of the everyday ways in which settlers are able to live in the city. I suggest that their practices aren’t those of resistance as much as those of political and material settlement; a dynamic, unstable and negotiated compromise between the government and the governed.

Yet, I don’t mean to suggest that infrapolitics is the primary mode that settlers to engage the state. As other scholars of the city have pointed out, settlers in Mumbai (and in Premnagar) frequently seek the same civil recognitions and protections afforded to other city residents. That is to say, they want to live in homes without the threat of government demolitions, they want reliable access to water, and to live in a neighbourhood environment where garbage is hauled away, roads are repaired, and medical and school facilities are available. Settlers have had varying degrees of success in receiving these state services as legitimate subjects/ citizens. Owing to the multiplicity of the state, and the differentiated regimes of recognition that different agencies draw on, the same settlers are often simultaneously constituted as illegal and legal; as members of political society and civil society. So for example, in their efforts to get their children admitted to public schools, they may be recognized as civil society, even as they claim water from their city councilors as political society. To the extent that recognition by one state agency facilitates recognition by others, many settlers in Premnagar and beyond are constantly deploying civil and political means to get themselves and their homes recognized by claiming the services of state programs. Their success at being recognized in one sphere of government (say at the Food Ration Card Office) facilitates their recognition in others.

Is there a book project that will be based on your work? What are the larger arguments that you anticipate making in the book that were not part of the article?

Yes, I’m currently developing the manuscript for my first book. With the working title, Infrapolitics: The Social Life of Water in Mumbai, the book thinks through questions of cities and states, democracy and citizenship through the materialities and politics enabled by the city’s hydraulic infrastructure. Loosely structured around the passage of water from country to city, and then to the ways it makes different neighborhoods viable, the book manuscript describes the multiple authorities that are produced through the production, journey and delivery of Mumbai’s water.

What research project/topic do you hope to tackle next?

I am working with colleagues on a new project that thinks across the rapidly proliferating infrastructures in the cities of Asia, Latin America and Africa, to examine the kinds of social and political lives they engender.

I am also now very interested in doing new fieldwork on sewers and gutters! Having spent as much time following water to the city, its homes and our bodies, I want to study the journey of water after it leaves our bodies. Sewage and drainage systems bring up a whole host of conceptual and political questions that are quite different from those of water supply. I’m interested in exploring why this might be the case.

Media Links

12. Rishta (relations) from Ek Dozen Paani on Vimeo. In 2008, I collaborated with an arts collective, CAMP, and two youth groups, Aagaz and Aakansha to produce Ek Dozen Paani (One Dozen Waters), a series of twelve short films. The films have been made with the members of the youth groups shooting on their own, bringing their footage into a collective pool, and writing over images in analytical, diarisitic or essay styles. Taken together, the twelve stories speak of water’s time and place, of leaky systems and subterranean flows, of struggle and/over imagination.

The Times of India. 2011. Water supply to Andheri, Jogeshwari gets better

Daily News and Analysis. 2011. 24x7 drinking water in Mumbai a distant dream

BBC News. 2009. Mumbai faces acute water shortage

Infrastructure Links

This article has been included in Cultural Anthropology's Curated Collection on Infrastructure. As an update, Anand offered the following materials to illuminate the issue of infrastructure.

Obama’s call to infrastructure

News and Information on Infrastructure in India:

Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM)

2011 article on JnNURM in The Indian Express

2009 article on Bandra Worli Sea Link bridge in Mumbai on website DNA

2010 article on budgeting of water infrastructure in Mumbai on website DNA

2011 article on crumbling economic bases for Indian infrastructure development in The Economist

Relevant Reading

Bayat, A. 1997. "Un-Civil society: the politics of the informal people." Third World Quarterly 18:53-72.

Chatterjee, P. 2004. The politics of the governed: Reflections on popular politics in most of the world. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ferguson, J., and A. Gupta. 2002. "Spatializing states: toward an ethnography of neoliberal governmentality." American Ethnologist 29:981-1002.

Gandy, M. 2002. Concrete and clay: reworking nature in New York City. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hansen, T. B., and O. Verkaaik. 2009. "Urban Charisma: On Everyday Mythologies in the City." Critique of Anthropology 29:5-26.

Holston, J., and A. Appadurai. 1996. "Cities and citizenship." Public Culture 8:187-204.

Larkin, B. 2008. Signal and noise: Media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

Swyngedouw, E. 2004. Social power and the urbanization of water: Flows of power.Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Questions for Classroom Discussion

1. Do you think the concept of ‘pressure’ clarifies the water issues of settlements in Mumbai? Why or why not?

2. Why does the author urge the readers to move beyond the binary of ‘haves’ and ‘have-notes’? What are more complex and interesting ways in which to think about social inequality in Mumbai?

3. What do you think the author means by ‘hydraulic citizenship’? What are ways in which you understand citizenship? How can we understand the notion of citizenship being related to access to resources?

4. Who are the important actors discussed in the article? What is their role in the ‘social life of water’ in Mumbai? What is the relationship between ‘technologies of politics’ and ‘politics of technology’ mentioned by the author?

5. How do moral considerations play a role (as a ‘politics of conscience’ described by the author) in how water is allocated?