Re-territorializing María Sabina: Huautla, Mushrooms, and Politics

From the Series: The Psychedelic Revival

From the Series: The Psychedelic Revival

Sitting atop the Oaxacan portion of Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains, Huautla de Jímenez, a small Mazatec town of around thirty thousand people, has received its fair share of international tourism. During the early 1960s, droves of European and American youths visited this Indigenous village searching for hallucinogenic mushrooms. Huautla had gained notoriety through the figure of María Sabina, the mushroom healer that allegedly first allowed “Westerners” to participate in a mushroom ceremony. Since then, Huautla and the figure of María Sabina have been intertwined with the so-called magic mushrooms.

In this brief essay, I pose the following question: what should the role of María Sabina and Huautla be in this new psychedelic revival? Although mostly happening in clinical settings throughout the global North, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom, the use of psilocybin has become de-territorialized—either elaborated synthetically in labs or through the online procurement of spores for home production. In this context, Huautla and María Sabina have become detached from their own political contexts. Thus, I propose an exercise of re-territorialization that recognizes Indigenous knowledge about hallucinogenic mushrooms not as depoliticized spirituality but as localized political knowledge.

Today, thirty-five years after her death, María Sabina continues to have an important presence in the Mexican countercultural movement that emerged through her interactions with R. Gordon Wasson in the 1950s (see Feinberg 2003; Faudree 2015). According to Eric Zolov (1999), the interest of urban, middle-class, mestizo, Mexican youth in hallucinogenic mushrooms emerged through the influence of international tourists who visited cities on their way to, or returning from, Huautla. Yet, the figure of María Sabina outlived that interest and became a multi-vocal icon that can represent, though not simultaneously, the depoliticized ideologies associated with the remnants of the hippie movement in Mexico and the recognition that indigenous knowledge is deeply political.

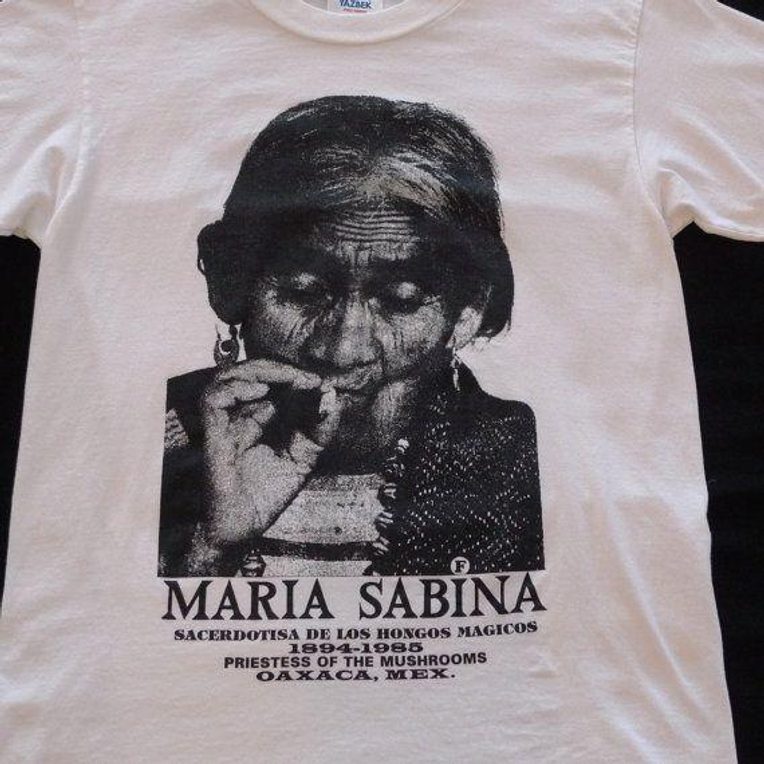

I grew up in several cities in northern and central Mexico, and I remember encountering the image of María Sabina in numerous and diverse places. Her face could as easily appear in popular science magazines, in posters next to contemporary and classic rock musicians, and on t-shirts. Her most famous image—that of her grabbing a joint roach in between her right thumb and her right index finger—is almost a fixture in popular Mexican imagery. Her indigenous identity implied but never fully made explicit, she did not seem to converse with other Indigenous historical actors but rather with the likes of John Lennon and Jim Morrison.

Like with other historical figures, her image was swallowed by a neoliberal multiculturalism that allowed her image to be consumed without engaging in her struggles as an Indigenous Mazatec woman. She was not seen as inhabiting a place or as part of a kinship network. Rather, she lived in the imagination of Mexican hippies and jipitecas. In the same way, in the contemporary psychedelic revival, mushrooms are seen as removed from specific places and from their original environments (their multispecies kin network). The international fame of María Sabina did not put Huautla on the map.

In Huautla, people are well aware of the global reputation of María Sabina. People will meet visitors and point out how they and/or their preferred mushrooms providers are related to her through kinship—this is especially convincing if they also happen to live in María Sabina’s old neighborhood, El Fortín. This kinship claim could be interpreted as a marketing strategy that Huautecos use to validate the mushroom experience they are selling to tourists (see Faudree 2015). But perhaps we could think of this claim to kinship through a different lens. Instead of classifying this expansive use of kinship with the depoliticized ideologies of many mushrooms seekers and mushrooms users in the global north, maybe we should reflect on the political potential that this form of expansive kinship offers for those who are part of the contemporary psychedelic revival (see TallBear 2016).

This form of making kin should conceptualize Huautla in a new way, as to include it in both the history of psychedelic revival and Mexican political history. Indeed, not long ago, the current Mexican president Andres Manuel López Obrador (known also as AMLO) visited Huautla. In a two-minute YouTube video, AMLO talks about Huautla while overlooking the mountainous range that surround the town: “I share with you this image. Huautla, the land of María Sabina, here everything is spirituality. But not just that, this Mazatec land is also the hometown of the Flores Magón brothers, forerunners of the Mexican Revolution.” With these two sentences, AMLO highlighted what often feels as two distinct worlds: spirituality (represented by María Sabina) and revolutionary politics (embodied by two anarchist Mexican thinkers).

Looking at the history of Huautla it is clear that politics and mushrooms have been intertwined for centuries—including the removal of hippies by the Mexican military in 1969. Thus, it is important to think about Huautla as both the land of María Sabina and the land of the Flores Magón brothers. A political location where knowledge about the world is produced. In fact, as Maurice Rafael Magaña (2020) documents in his book Cartographies of Youth Resistance: Hip-Hop, Punk, and Urban Autonomy in Mexico, there is a long tradition of merging “disparate” symbols throughout Oaxaca. Art collectives, such as Arte Jaguar, can just as easily portrait Ricardo Flores Magón with a punk hairstyle or paint a mural of María Sabina next to graffiti. Spirituality and politics need not be disconnected if we re-territorialize María Sabina, and see Huautla and the Sierra Mazateca as places that, besides producing mushrooms and attracting tourists, have also produced knowledge and political ideas.

The call to re-territorialize indigenous knowledge is also a call to re-politicize the local. The re-territorialization of María Sabina and Huautla offers the possibility to think about the current psychedelic revival in political terms that go beyond the decriminalization and the popularization of hallucinogenic substances in select cities in the global north.

Faudree, Paja. 2015. “Singing for the Dead, On and Off Line: Diversity, Migration, and Scale in Mexican Muertos Music.” Language and Communication 44: 31–43.

Feinberg, Benjamin. 2003. The Devil's Book of Culture: History, Mushrooms, and Caves in Southern Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Magaña, Maurice Rafael. 2020. Cartographies of Youth Resistance: Hip-Hop, Punk, and Urban Autonomy in Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

TallBear, Kim. 2016. “The US–Dakota War and Failed Settler Kinship.” Anthropology News 57, no. 9: e92–e95.

Zolov, Eric. 1999. Refried Elvis: The Rise of the Mexican Counterculture. Berkeley: University of California Press.