Reinventing “Others” in a Time of Ebola

From the Series: Ebola in Perspective

From the Series: Ebola in Perspective

Ebola invaded Sierra Leone using an eerily similar path as Revolutionary United Front rebels twenty-three years ago. From Kailahun, the farthest eastern district, the virus has coursed its way, inch by destructive inch, into the heart of the country and the imaginations of Sierra Leoneans. Along the way, it has met with varying public attitudes and a government response that parallels what the rebels encountered as they marauded through the countryside to eventually lay waste twice to the capital Freetown. It is in the competing narratives of the outbreak that the comparisons have been most striking, however, as two publics have emerged—each adhering to a version of events to reinvent others in a time of Ebola. This essay narrates these efforts and reflects upon the implications for political stability in the Mano River region.

In 1991 residents of Kailahun knew war had been raging across the “border”1 in Liberia for at least two years before they too came under assault at Bomaru on March 23. In the case of Ebola, they did not have a name for the new pestilence or where it came from. They consulted their traditional healers who had cured all kinds of illnesses in the past and sustained their communities for generations, and they died. They went to the barely staffed government health centers to consult “modern medicine,” they still died, and they continued dying. Some of the health care workers brave enough to care for them died without knowing what had prematurely dispatched them to meet their ancestors.

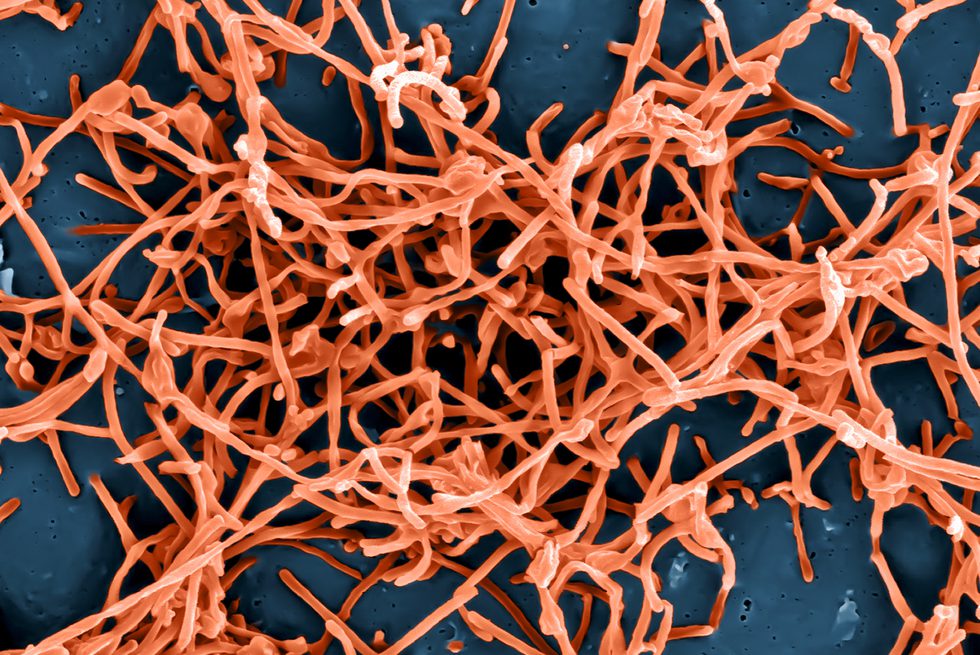

Soon modern medicine had a name for this “mysterious” fever. It was Ebola and they had caught it from eating bushmeat they had been eating since the beginning of time. No, they had caught Ebola from eating bats that fed on the fruits around the villages. “But we do not eat bats or ‘strange creatures.’ They are haram in our faith,” several protested. “You must have brought the fever into Sierra Leone after attending the funeral of dead relatives across ‘the border’ in neighboring Guinea where the outbreak is ‘much more serious,’” they were told.

Then the government fired the first salvo. On June 17, 2014, the Health Minister, Miatta Kargbo, appeared before the Parliament of Sierra Leone and testified that the virus was spreading due to ignorance and the refusal of victims and their families to seek medical care in hospitals. Perhaps the most revealing aspect of the minister’s testimony was singling out, and calling by name, two deceased health care workers who, according to her, had helped spread Ebola by engaging in promiscuous sex while on duty. Most of the audience responded with shock at the minister’s public naming and shaming of her staff, but others applauded the opportunity to reinvent others and blame them for the calamity.

The minister worked in the United States before her ministerial appointment. Surely she knew a thing or two about patient confidentiality. She has since been fired. No, not fired. She has been “relieved of her duties” by His Excellency the President “Dr.” Ernest Bai Koroma and recalled to the State House to serve in the Strategy and Policy Unit.2

Counter narratives fired back. They could draw upon history for evidence. In the 1980s, All People's Congress (APC) government officials signed deals with foreign firms allowing them to dump toxic industrial waste into the territorial waters of Sierra Leone. Was the APC up to its old tricks? In their version of events, several clinical trials of Ebola involving foreign interests had all taken place suspiciously close to the timing of the current outbreak. Why did Ebola not strike Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone during the lean war years when rebels and innocent civilians lived in forests for extensive periods of time, ate copious amounts of bushmeat, and survived on anything? Why would anyone carry out an Ebola trial in West Africa, where there had never been an Ebola epidemic before? Why would anyone be interested in a bioterrorism threat test in Sierra Leone of all places?

It is this back-and-forth that has led to two publics about Ebola and the invention of the other, threatening the fragile postwar political stability in the Mano River region. One narrative blames victims of Ebola for their “ignorance,” “backwardness,” and suspicions of modern medicine, even though they were showing up at health centers in regular streams and infecting health care workers. The counter narratives question the origins of the current outbreak, using “conspiracy theories” and stubborn correlations between the presence of the All People’s Congress party in power and major national and regional calamities.

Many wonder if the virus would have been approached differently if it had emerged in the northwest, where most of the senior APC officials, including the president, call “home.” Indeed, only as the disease crossed from the southeast into other parts of the country did the crisis response intensify and the government finally enlist the help of the international community to help fight Ebola.

In a cruel, ironic twist, the government’s handling of the epidemic has fit snugly into metanarratives of global inventions of the “other.” The region is now under de-facto quarantine. Flights have been suspended and foreign embassies and mining companies have repatriated their staff. Everyone has truly gone “home,” and Robert Kaplan is probably saying “I told you so” about disease and chaos in West Africa.

Nobody deserves Ebola. You wouldn’t wish this plague upon your worst enemy. Peace in the Mano River Union is imperiled once more as communities reinvent “others” in a time of Ebola.

1. This and others are direct quotes or contested meanings that the lack of space could not allow me to pursue.

2. In the interest of full disclosure, this author too served in that same Strategy and Policy Unit of the Office of the President and found it the most dreadful waste of time, energy and sanity.