Religion as Politics by Other Means

From the Series: Ukraine and Russia: The Agency of War

From the Series: Ukraine and Russia: The Agency of War

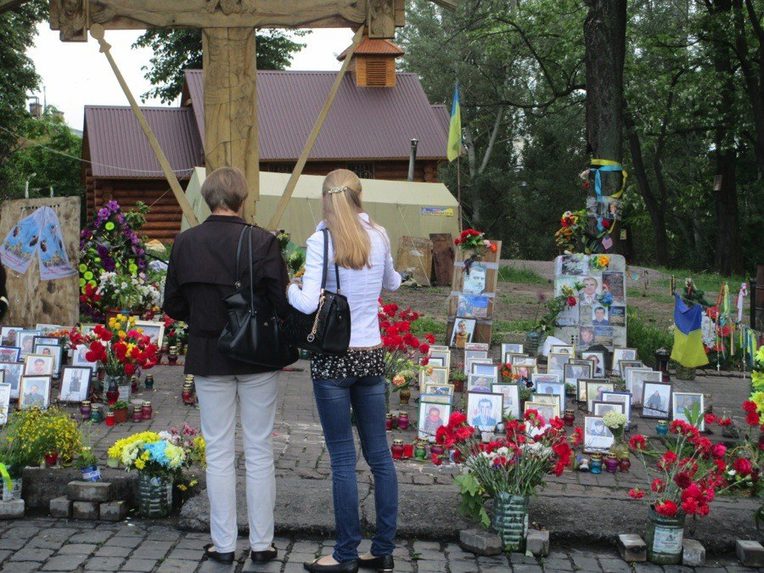

When popular disgust with corrupt and self-serving governance triggered massive street protests in Kyiv in November 2013, a plethora of religious groups joined in. The audibility of the religiously inspired rhetoric of the protesters and the visibility of religious symbolism and clergy on the Maidan, Kyiv’s central square where most of the protests took place, does not, however, reflect a “post-secular” rediscovery of religion. Rather, the instrumental use of clergy, religious sentiment and transcendent symbolism on the “EuroMaidan” reflects the emergence of conditions in which religion is capable of playing an expedient role in the process of forging a new governing and moral order.

Given the pervasive religious and moral justifications for the positions of each side in the conflict, it is remarkable that the religious dimension of this struggle has not received more attention in the popular press. The Ukrainian protesters harnessed religiosity to generate social solidarity and feelings of empowerment against a perceived corrupt, abusive, and unjust state. Religion was mobilized to cultivate a capacity for and will to virtue (Shell 2009, 137), which was deemed essential for maintaining self-sacrificing support for horizontal forms of activist leadership and non-violent responses to state-led aggression. Moreover, assertions of transcendence fed convictions that the massive efforts required of a humiliated and tired population to radically redirect governing practices were indeed possible (Fylypovych and Horkushi 2014). On the other hand, the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church declared “godliness” (sviatost) a Russian national ideal and maintains that Ukraine is an integral part of the “Russian World” (Russkii Mir), meaning eastern Orthodox civilization. Correspondingly, Vladimir Putin uses a shared Orthodox faith to identify “Russian compatriots” (sootechestvenniki) and to assert his right to protect them (Wanner 2014).

Carl von Clausewitz claimed that war is a continuation of politics by other means. The same could be said of religion in the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine. After seventy-three years of governing practices in the Soviet Union that were designed to diminish belief in the supernatural and eradicate the social and political capital of religious institutions, today the public sphere, politics, and even everyday individual practices cannot be understood without some consideration of religion. Religious rhetoric and practices shape subjectivities, patterns of governance, and power relations. Reciprocally, the needs of the state shape the dynamics of religiosity. Over time, the intensity of this symbiotic relationship has simply vacillated (Wanner 2012).

Institutionalized religion as well as improvised, lived religious practices in both Ukraine and Russia have been powerfully affected by what I call “syncretic secularism,” meaning “a blending of belief, doubt and non-belief with the desire to belong and the refusal to be coerced by institutions” (Wanner 2014, 436). Syncretic secularism yields a sensibility and responsiveness to religiosity and religious identities alongside a cynical suspicion of persons in authority, including clergy, and the institutions they command. Syncretic secularism ultimately expands the ways the political and religious can be melded together to greater effect.

In analyzing secularism in Europe, José Casanova (2013, 38) suggests that a series of secularizations have occurred there that involved a shift from a territorial anchoring of religion in confessional states to states that fostered a public sphere (more or less) characterized by a certain neutrality toward religion. As a by-product of this shift, confessional identities gradually ceased to hold meaning. In essence, processes of secularization in Europe centered on de-confessionalizing states and dis-establishing state churches.

This process never really occurred in Russia. The imperial Russian state celebrated the triad of orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationality to the end. In the Soviet Union, only the Russian Orthodox Church functioned somewhat openly. Ukrainian churches, in contrast, were driven underground. This positioned Ukrainian religious institutions as antagonistic to state structures, which were perceived as imperial, oppressive and Russian. The Russian Orthodox Church, on the other hand, maintained some kind of accommodation to the state in the name of a governing principle called simfoniia, or harmony. Either way, in both Russia and Ukraine, religious institutions, as syncretically secular institutions, have historically played a vital role in governance.

Religion is such a powerful undercurrent in the violence on the eastern Ukrainian-Russian border because it plays a key role in defining space as it relates to issues of sovereignty, borders, and sacredness. Rituals, relics, and practices emplace practitioners in a particular location by conjuring up the sacred in the form of visions, inclinations, and sensations, which not only evoke the past but also make the physical presence of the past palpable. More than just a trigger for the recall of certain historical memories, the emplacement of religious rituals in particular sites generates an encounter with the past, evidenced by the tangible sensations experienced in the bodies of practitioners. In this way, religious practices have enormous political utility. They are able to serve as vehicles for experience and validate a particular historical interpretation with the aim of realizing specific political goals in the present.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has justified Russian intervention in Ukraine in its overt and covert forms by asserting that Ukraine is part of the “Russian World.” This is the phrase the Russian Orthodox Church uses to refer to its canonical jurisdiction that includes Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, echoing the imperial domain that united Great Russians, Little Russians and White Russians, as these three groups were known, under the tsarist empire. Religion offers a divine vision of the past that can be encountered and experienced as sacred in the present. Along with references to the “Russian World,” Putin also resurrects the historic name of these disputed eastern Ukrainian regions, Novorossiia, or New Russia, a designation given when these lands were seized from the Ottoman Empire in the late-eighteenth century. Yet, alongside Putin’s use of a historically religious domain to underwrite his imperial political ambitions, orthodoxy underpins a “community of interpretation,” some members of which find his use of violence abhorrent against co-believers and “compatriots,” meaning all Slavic peoples living in the “Russian World.” So while the spatial equation of religious unity with political unity generates legitimacy for this political project, the means chosen give pause to some.

Divergent correlations as to how religious affiliation should define political space have emerged in Ukraine. Although the Russian Orthodox Church is intentionally multinational, most eastern Christian churches are organized on a nation-state principle, with each church serving its own people and its own state. This is why we have the Greek Orthodox Church, Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Romanian Orthodox Church, and so on. This institutional configuration suggests that, after two decades of independent statehood, it is time to create an independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Although the Ukrainian population is about one-third of Russia’s, nearly two-thirds of all the Russian Orthodox parishes are located in Ukraine, and many clergy come from Ukraine. There are also numerous monasteries of historic significance for all Orthodox Christians in Ukraine.

In essence, the spatial dimensions projected onto an ascribed religious identity born of a single faith tradition simultaneously validate imperial ambitions and a separatist nation-state model. As a governing principle, syncretic secularism means that compared to the Soviet period, Russian and Ukrainian societies—and the politics that regulate them—have become simultaneously even more secular and even more religious. Political tensions have magnified religious tensions, reinforcing the impetus for divisions and separations of all kinds, which suggests that these two countries are increasingly separated by a common faith.

Casanova, José. 2013. “Exploring the Postsecular: Three Meanings of the ‘Secular’ and their Possible Transcendence.” In Habermas and Religion, edited by Craig Calhoun, Eduardo Mendieta, and Jonathan VanAntwerpen. Malden, Mass.: Polity Press.

Fylypovych, L. O., and O. V. Horkushi. 2014. Maidan i Tserkva. Kyiv: Sammit-Kniha.

Shell, Susan Meld. 2009. Kant and the Limits of Autonomy. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Wanner, Catherine. 2014. “‘Fraternal" Nations and Challenges to Sovereignty in Ukraine: The Politics of Linguistic and Religious Ties.” American Ethnologist 41, no. 3: 427–39.

Wanner, Catherine, ed. 2012. State Secularism and Lived Religion in Russia and Ukraine. New York and Washington D.C.: Oxford University Press and Woodrow Wilson Center Press.