Rescripting Visual Codes: A Poetic Translation

From the Series: The Postcard Series: Rescripting Visual Codes

From the Series: The Postcard Series: Rescripting Visual Codes

This text was originally published in Absinthe: World Literature in Translation.

An elderly figure stands dignified on a roadside, emerging from a backdrop of cane fields.

Her long skirt lingers in a gentle sweep. The fabric curves along her lead leg, bent forward, as her torso turns slightly toward the one framing this picture postcard. She dares to confront the gaze of an unseen photographer, a scornful look that emanates from the dark shadows cast on her face. These defining shapes contour a furrowed brow, high cheekbones, and pursed lips. Yet, her beautiful face, graced with age, holds a look that cannot be contained by shadow, or frame, or colonial optic, or photographic convention.

The vibrant constellation of brow, cheekbones, and faintly illuminated lips refuse the terms of spectatorship and surveillance. It is an unmistakable expression that eludes the enclosure of touristic capture, at the hands of an exalted French descendant, who promulgated the northern landscape of Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic in the 1900s. His name, appearing across public records and genealogical accounts, has become fodder for folk historians and deltiologists. The beautiful silhouetted figure remains unnamed and tenuously linked to the plots of colonial promotion and technological innovation.

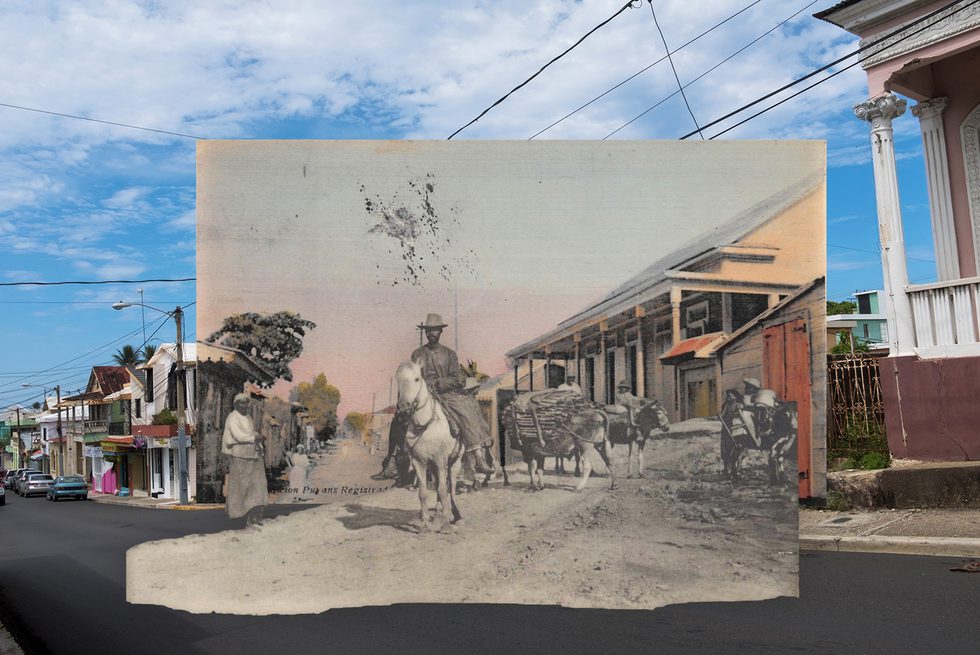

Looking at the image, in digitized form, her shadowed expression absorbs my attention, never mind the undulating dirt path that spills out to the bottom edge like a limelight; much less the gallant horseback rider emplaced at the center of the frame. She is conscripted to the periphery, on the side of the road; a supporting actor in a visual composition that foregrounds a cavalry of workers, who ride towards the city on horses and mules piled with harvested cane. She stands at the borderline, a boundary that demarcates the path on which light refracts; a liminal zone between motion and stasis, the road and arable land. She is denied access to both geographies, historically romanticized in mutually-constituting relation.

The caption further disavows her presence.

Campesinos entrando a la Población (“Farmers entering the City”). She is textually written outside the free zone of the city, settlement, or civic population. Her labor recedes from the history of settlers and developers. By this logic, she also disappears from a rural class. Campesinos entrando a la Población. This phrasing enacts a gendered performance of entwined masculinity and rurality. Situated at the edge of constructs, she creates transgressive geographic possibility, with arms extended in a 90-degree angle, and hands cupping an indiscernible object. Her stealth gestures and embodied prowess are protected under the cover of opacity. What is made knowable to the glare of photographic visibility is a facial expression of open contempt, of radical looking.

I stumbled upon her daring look while browsing diffuse archives of digitized postcards, from virtual museum collections to auction interfaces.1 I had been searching for images of a now-derelict hotel on the northern coast, in an attempt to locate and retrace strands of family history, particularly my father’s working life in tourism. It is a personal excavation that runs parallel to an ethnographic study of urban sociality and senses of belonging amid a present-day tourism renewal project. I yearned to see the architectural site that condensed the journeys of internal migrants, like my father, who sought to make a life and reinvent themselves in tourism spaces after the 1970s. Unexpectedly, I caught glimpses of everyday life for African descendants—in the wake of sizable flows of free migrants from North America, Turks and Caicos, Bahamas, and Haiti, attesting to the Afro-diasporic connections that unfolded throughout the northern region.

Black emigration had been endorsed under the tenure of Haitian governance on the island amid tensions between the transatlantic slave trade and growing abolitionist struggle. After Pierre Boyer’s presidency was overthrown, communities of Black migrants and their descendants resided uneasily in the port town of Puerto Plata, the threat of reenslavement loomed heavy. The post-Boyer era was marked by annexation schemes, a return to Spanish colonial rule, and a guerrilla war following antiblack mandates to outlaw machetes and persecute members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which spurred repatriation of refugees. Militant activists and freedom fighters from both sides of the partitioned island banded together against the racism and colonization that engulfed the northeastern region and agitated against the diminished subjecthood imposed by external power (see Horne 2015; Eller 2016)).

The few images of African descendants that materialized in my search are scattered across multiple postcard series. The special edition collections combine touristic sensibilities with social documentary and naturalist ways of seeing. These collections emerge from what enthusiasts call the “Golden Age” of postcards, characterized by collotype printing methods and divided backs, designating surface area for postal address and personal messages. Each collection exhibits distinct tonal ranges. One contains a broad and subdued palette of mid-tones, the other captures the extremes of light—an interplay of brightness and opacity. If a figure is close enough to the camera, and in focus, crisp imagery renders on the printed matter. The majority of public scenes, however, are composed at a distance. The photographer’s absent presence registers the sweeping view of a distant observer. The intricate mid-tone range of the former collection produces delicate details. The features of a face, for instance, are unequivocal despite the shadows.

The afterlives of these picture postcards circulate in virtual networks as visual data of colonial geographies of power. Looking at the images that flicker on digital screens, I wade in the excess of violent arrangements, the residues of physical presence, and the atmospheric quality of freedom landscapes. These circulating objects bring me in contact with lives that are absented from regional heritage markers, though ephemerally surface in social memory. By bearing witness to these images, I want to attend to the quotidian realities of Black diasporic life within environments imbued with the promise of liberation. How does one reconfigure the violent codes that enclose their social lives and muffle the sounding of their voices? How does one reconcile their photographic presence as figuration and shadowy abstraction? Is it possible to engage the shadows of digitized collotype cards as refusal, as black interiority, as open cover for surreptitious exchange and radical imagination?

The elderly Black woman appearing at the edge of the road, on the outskirts of the city, stood at the threshold of dominant geographies and political subordination—between Spanish recolonization and American occupation. Attending to her quotidian gestures along with those of younger generations of Black women occupying public space demands that we stretch our sensory capacities, reattune our modes of perception.

I fixate on small motions and keenly listen to inaudible utterances.

This attunement renders a looking practice that touches their historical presence and transfigures their positioning as surplus figures in photographic frames. This mode of looking seeks to reclaim the sentience of their embodied existence.

But I want to do more.

In the act of haptic viewing and kinesics study, the authority of the postcard remains untouched. I resolve to fuse this mode of looking with creative digital practices—methods of cutting, pairing, and overlaying—intent on reworking visual codes. This integrated praxis can be described as poetic translation: an alteration of digital forms that concurrently hinges on and expands the expressive qualities of the photograph. The term poetic, and its etymological kin poeisis, refer to a process of making that emerges at a threshold. This act of poetic translation imagines authorized views of social scenes anew. By layering and rearranging imaged figures and landscapes, I attempt to multiply temporalities and perspectives, displace the singular spectator, and open up what may have occurred yet the documentarians left unrecorded (see Hartman 2008; Philip and Boateng 2011; Campt 2017).

The diffuse archive of postcards circumscribes Black laborers outside of the city, on the verge of crossing spatial boundaries. The captions reinforce the social segregation pictured between city dwellers and rural inhabitants. Vendedores Campesinos fuera de la Ciudad (“Agricultural Vendors outside of the City”). As a counter gesture, I craft a creative interpretation of their ordinary movement through the urban center. Reimagining their quotidian tracks, descendants of Black migrants transgress representational maps. Creating a palimpsestic city, composed of multiple paths, breaks the visual grammar of reifying optics. The convention of perspective becomes undone.

Stasis gives way to motion.

Afro-diasporic motion in place, in situ. The constant practice of freedom. The lines of flight carved within ever-encroaching limits.

On the other side of the road from which the elderly figure looks, a young woman stands, nearly hidden. She is one of few anonymous figures of Black womanhood depicted in the series. They are often positioned by the right edge, bodies still or ambling along the frame. They are typically nestled in intimate sociality among an assembly of majority-male laborers. The young woman across the road from the elderly figure stands next to a mule, tethered to a wire fence, and a tall shadowed person donning a luminous fedora, ubiquitous among male farmers. Amused by the crowd of idling workers, she cups her mouth, obscuring a public display of joy.

Her demure laugh radiates despite the protective gesture.

She revels in the feels of lighthearted exchange, the impression of public banter, or the characteristic interplay of verbal registers. The surge of joy is hers alone. It is a small moment teeming with liveliness.

In the image, captioned "Agricultural Vendors Outside of the City," two women are enthralled in conversation at the far end of a horizontally dispersed ensemble. They are abundantly clad in fabrics—long sweeping skirts, billowy tops, and headscarves—reminiscent of the clandestine sartorial practices of enslaved and free African women. Their angled postures lean into one another. One woman is photographed in mid-speech, lips parted. Her right arm tightly cradles a vague object against her side body. Her left arm is bent towards her head, with splayed fingers by the edge of her scarf, indicating the magnitude of a certain matter. Her gestures enunciate furtive speech that shape a verb.

The other woman listens intently.

She stands barefoot, at ease, her body quietly sways. Her profiled face, fully given to the exchange, and cupped arms resting in front of her skirt, are profusely cast in black. Under shadow and voluminous fabric, the figures form a space of interiority in public space. They carve a loophole of love and sisterhood, of intimacy and diasporic Afro-feminist connection. The buzz of quiet utterances exceeds the photographic field.

Breaking the repetition of paired figures at the photograph’s edge, one rare image portrays a single Black girl walking barefoot, off frame. It is a haunting image of an adolescent figure—unescorted and unaccompanied—strolling along a city street juxtaposed with a public scene of disciplinary action. In the background, two figures stand side by side, in front of a shuttered lot, adjacent to a two-story Victorian house. From the unpaved street, a man clad in a dark suit holds a deceptively thin cane, or linear weapon. His ominous silhouette oversees the couple’s coerced posture: a compelled stillness, motionless. In the foreground, the singular girl crosses the spectacle of managerial control. She dons a dark flowing dress that brushes her ankles. She holds a large, glowing object like a star fruit or papaya. Her right foot, firmly planted on the pavement, meets an elongated shadow that stretches before her.

The shape shifting shadow beckons her, as if waving for attention.

Her left foot hangs in hazy suspension. The photographer’s long exposure catches the blur of errant motion. She eludes fixity. The girl notices the photographer, watching her. She participates in a play of looks: her curious stare, the overseer’s observation, the couple’s downcast eyes, the photographer’s all-seeing view. Her blurred foot ruptures the plantation that folds into the city block (see Hartman 2019) Along with her shadow, she choreographs a way of possibility (see Cox 2015).

1. Key among such databases are the digitized postcard collections of Centro Cultural Eduardo León and auction sites like eBay and WorthPoint.

Campt, Tina, M. 2017. Listening to Images. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Cox, Aimee, M. 2015. Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press

Eller, Anne. 2016. We Dream Together: Dominican Independence, Haiti, and the Fight for Caribbean Freedom. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press

Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 26: 1–14.

———. 2019. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York: W. W. Norton

Horne, Gerald. 2015. Confronting Black Jacobins: The United States, The Haitian Revolution, and the Origins of the Dominican Republic. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Philip, Marlene NourbeSe, and Setaey Adamu Boateng. 2011. Zong! Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press