Resource Frontiers in the Pilbara: Lifestyle Choices?

From the Series: The Pilbara Crisis: Resource Frontiers in Western Australia

From the Series: The Pilbara Crisis: Resource Frontiers in Western Australia

The current crisis in the Pilbara opposes economic arguments about viability that center on education and employment against those privileging culture and history. Multinational corporations, the state, Indigenous peoples, heritage experts, and other decision-makers draw on the rhetorics of heritage, rights, and sustainability in managing the environment, revealing the imbrication of global heritage and environmental politics and the ways in which heritage intersects with indigenous rights and environmental protection. As a resource frontier (Tsing 2005)—the transactional space around people and resources that engenders revitalization and renewal, as well as inequality, exploitation, and displacement—the Pilbara offers a means of understanding key debates regarding the relationship between Indigenous people and the modern nation, and the place of the West in larger schemes of national and regional identity. The history of Aboriginal people and industry, particularly mining, in these Wests, provides an avenue for exploring larger debates about Indigenous people and modernity.

The 2012 Boyer Lectures delivered by the Aboriginal intellectual Marcia Langton sparked heated public debate. In the lectures, Langton (2012) argued that Aboriginal life today is fully commensurate with a modern economy, seeking to reverse the historical misconception that Aboriginal Australians are primitive and unable to participate in the modern world. However, controversial aspects of her analysis included her rejection of the environmental movement and the Left, historically considered champions of the Aboriginal cause, and her praise for a new alliance with mining companies. Critics (e.g., Frankel 2013) suggested that her “simplistic narrative of goodies and baddies based on an equally simplistic political geography” unfairly labeled the Left as racists, while others pointed out that she had failed to disclose significant funding she had received from mining interests. Supporters (e.g., Skelton 2013) praised her rejection of historical stereotypes of Aboriginal Australians as abject: a powerless, downtrodden, oppressed minority.

These contrasting narratives of Aboriginal life are being played out in the Pilbara right now. Australian Aboriginal aspirations for the future typically emphasize a desire for alternative forms of economic engagement that permit the maintenance and enhancement of Aboriginal institutions, including links to Country and the maintenance of Indigenous institutions associated with family and kin (Scambary 2013). Archaeological and historical sources reveal Aboriginal involvement in extractive industries from the 1800s onwards: marine animals (whale, trepang, turtle, pearlshell), timber, guano, minerals, and other gases (Paterson 2015; Walsh 2015). The Pilbara crisis maps the rapprochement praised by Langton onto the context of a longer debate about remote Aboriginal communities and culture, a debate that reveals the intersection of heritage, Indigenous issues, and frontier technologies.

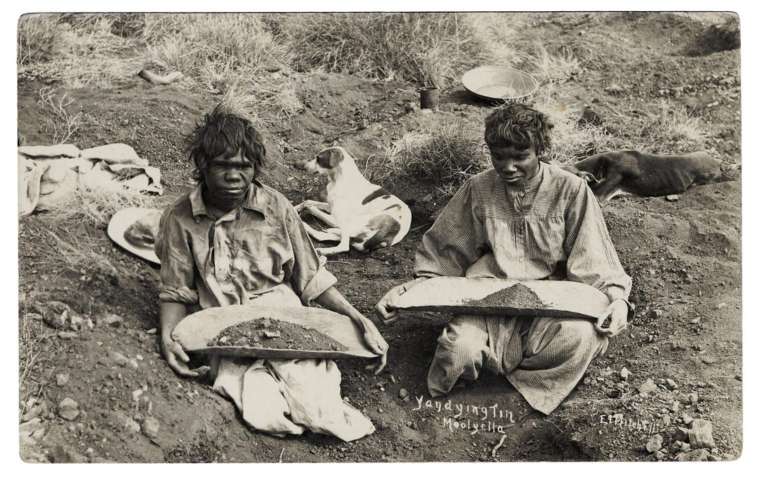

The historical derivation of today’s debates continues to be overlooked by policymakers and corporations, despite their enthusiastic use of Aboriginal culture and heritage in promoting corporate social responsibility programs. One key aspect of these debates is the role that representation has played in shaping popular opinion and public policy. The first Western sightings and images of Australia were made on the continent’s western coast, and perceptions of the West—particularly northwestern Western Australia—have continued to shape debates about national and regional identity, race relations, and Australian culture. Although mining has long been central to Australian notions of national identity as a source of prosperity and development since the mid-nineteenth century, mining narratives—and profits—have usually centered white male heroes. The important role of women and Aboriginal people has remained invisible in these accounts, echoing the historical exclusion of these groups. After tin was discovered in the Pilbara in 1882, Aboriginal people introduced the yandy, a wooden dish traditionally used in winnowing grass seed or other foods, as a tool for panning for tin and gold. Yandying was described over and over with evident fascination, such as when a journalist for the Sunday Times noted on January 18, 1914 that only Aboriginal women had mastered “the inimitable and delicate manipulation of this simple device.

In May 1946 Aboriginal pastoral workers walked off stations across the Pilbara in Western Australia in a campaign that later developed into the self-supporting Pindan Cooperative Movement. This was not just an industrial action but also a broadly based political movement that aimed to secure a range of rights for Aboriginal people and to improve their standard of living (Hess 1994). The strikers supported themselves through yandying for minerals and other forms of small-scale industry; they also formed a mining company, Northern Development and Mining, the first Aboriginal-owned company in Western Australia. The company bought Yandeyarra station, where it constructed a school and hospital clinic, as well as three other stations. It also built a home for Aboriginal hospital outpatients at Marble Bar and funded capital works such as roads and equipment purchases (Wilson 1961). The police and other officials ruthlessly opposed the cooperative movement. Aboriginal people left the declining pastoral industry during the 1960s and, as mining developed in the Pilbara, both government and industry excluded Aboriginal people (Edmunds 1989).

Around 2005 the largest rush in Australian history began in the Pilbara region and transnational resource companies recognized that in order to gain a social license to operate, they would have to develop sound relations with Aboriginal communities and to pursue sustainable regional economies involving greater Indigenous participation. One key finding of research into these relationships is that a dissonance exists between Aboriginal expectations of noneconomic benefits from mining agreements and the limits on mining corporations’ capacity to deliver such benefits (Taylor and Scambary 2005). In regional and remote Australia, mining developments may be the only contributors to regional economic development, and thus they become a focus for Indigenous people seeking the delivery of services normally provided by the state. Corporations are increasingly funding Indigenous health, housing, and education programs in order to develop the competencies required for mine employment. The industry has also been (reluctantly) funding underresourced native title representative bodies to resolve legislative processes, also normally funded by the state, so as to obtain timely security of tenure for mining and exploration activities. This emerging role for industry contrasts with public Indigenous programs, which are the targets of funding cuts, increased governmental scrutiny, and devolution of functions to mainstream government departments (Scambary 2013, 233).

The challenges faced by local Indigenous people stem from disadvantages in health, employment, life expectancy, child mortality, and household income, exacerbated by limited formal economic opportunities. However Benedict Scambary’s (2013) recent analysis of three mining agreements in north Australia, including the Yandi Land Use Agreement in the Central Pilbara, argues that across Northern Australia, innovative partnerships that emphasize Indigenous land management practices are beginning to recognize cultural value in economic arrangements. These partnerships provide the opportunity for the continuation of cultural traditions and the maintenance of heritage and distinctive identities. A historical perspective thus provides some lessons for the present: mainstream views do not recognize that Indigenous demands are not just economic in nature, but also involve access to land, heritage, and identity. In the absence of federal resources, mining companies are being required to support a wide range of social functions in order to operate, with mixed outcomes for Aboriginal people.

Edmunds, Mary. 1989. They Get Heaps: A Study of Attitudes in Roebourne, Western Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Frankel, Boris. 2013. “Opportunity Lost. Arena Magazine, no. 122.

Hess, Michael. 1994. “Black and Red: The Pilbara Pastoral Workers’ Strike, 1946.” Aboriginal History 18, nos. 1–2): 65–86.

Langton, Marcia. 2012. “2012 Boyer Lectures. The Quiet Revolution: Indigenous People and the Resources Boom.” Radio National, November 18–December 2.

Paterson, Alistair. 2015. “Nothing New? The Heritage of Indigenous People in Resource Industries in Australia’s Pilbara.” In “The Pilbara Crisis: Resource Frontiers in Western Australia,” edited by Melissa F. Baird and Jane Lydon, Cultural Anthropology website, December 16.

Scambary. Benedict. 2013. My Country, Mine Country: Indigenous People, Mining, and Development Contestation in Remote Australia. Canberra: Australia National University E Press.

Taylor, John, and Benedict Scambary. 2005. Indigenous People and the Pilbara Mining Boom: A Baseline for Regional Participation. Canberra: Australia National University E Press.

Tsing, Anna. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Walsh, Aileen. 2015. “A History of Forced Removal: Diminishing Returns in the Northwest of Western Australia.” In “The Pilbara Crisis: Resource Frontiers in Western Australia,” edited by Melissa F. Baird and Jane Lydon, Cultural Anthropology website, December 16.

Wilson, John. 1961. “Authority and Leadership in a ‘New Style’ Australian Aboriginal Community: Pindan Western Australia.” Masters thesis, University of Western Australia.