This post builds on the research article “Ruderal Ecologies: Rethinking Nature, Migration, and the Urban Landscape in Berlin,” which was published in the May 2018 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Ashley Elizabeth Drake: The research for this article emerges from fieldwork with immigrant communities, environmentalists, ecologists, and other urban residents in Berlin and takes place across a diverse urban landscape of parks, gardens, and wastelands. What initially inspired you to develop an interdisciplinary project that explores how “urban ecologies, globalization, and racial exclusions are entangled with one another”? What was it like to sift through those entanglements?

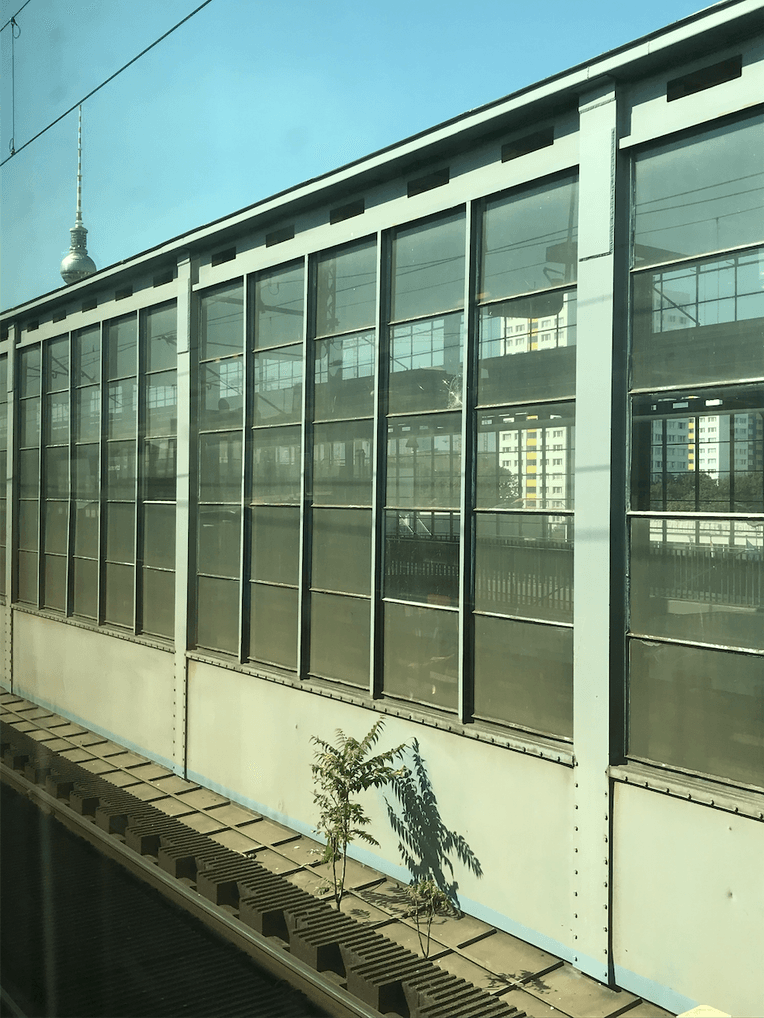

Bettina Stoetzer: Fieldwork often takes unexpected turns. Perhaps ironically, one of these unexpected turns, for me, occurred at the peripheries of the city of Berlin. Grappling with the legacies and changing dynamics of nation-building and racial exclusion in Germany quite literally led me into the woods—and to many other landscapes in Berlin and its peripheries. When I began preliminary fieldwork in Germany in the mid 2000s, I spent a lot of time with refugees and activists in the forests of Brandenburg (the state and region surrounding Berlin). Located in one of the most sparsely populated areas in Germany, these forests had, at the time, become a temporary home for many asylum seekers from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, who found themselves living in abandoned East German military barracks just a few kilometers away from Berlin. This situation was the consequence of a series of profound transformations that had redrawn Europe’s and Germany’s borders a few years earlier. The 1990s had been marked by heated debates about migration and asylum. For example, in 1992, close to half a million people, many of them fleeing the war and ethnic violence unfolding in former Yugoslavia, had applied for asylum in Germany. With the collapse of socialism and the fall of the Berlin Wall (which just had its thirtieth anniversary), Germany’s unification process also triggered a resurgence of nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiments across the country, including violent attacks on refugee and migrant worker homes (that housed people from the Balkans but also from Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East) in several German cities, such as Hoyerswerda and Rostock—a development that we see occurring again with increasing frequency since 2015. As a response to the 1990s political situation, European Union (EU) and German asylum policies underwent drastic changes and restrictions. Asylum numbers decreased to historic lows in Germany from the mid 1990s to 2009, and many refugees were transferred to remote locations in Berlin’s forest peripheries as well as other to rural areas in former East Germany.

By the mid 2000s, refugee activists and advocates across Germany were thus organizing against the spatial isolation, everyday racism, and restriction of mobility that asylum seekers were facing in these locations. Being involved in and engaging with some of these activist and advocacy networks, I was interested in mapping on-the-ground negotiations of what constitutes “antiracist practice” among different actors in the Berlin area, including refugees, advocates, social workers, and local residents. Since the 1990s, many scholars, artists, and activists of color based in Europe and Germany had illustrated the limits of research and activism that ignored the political realities through which migration, displacement, and gender inequalities were deeply racialized (Hügel-Marshall 1993; Gelbin, Konuk, and Piesche 1999; Gutiérrez-Rodriguez and Steyerl 2003; Oguntoye, Ayim, and Schultz 2007; Nghi Ha 2010). My first book InDifferenzen: Feministische theorie in der antirassistischen kritik (Stoetzer 2004) traced some of these transnational feminist and anti-racist conversations—and examined their critiques of whiteness and the production of social indifference in post–WWII Europe. Conducting fieldwork at Berlin’s forest peripheries, I thus wanted to gain deeper ethnographic insight into the ways in which antiracist coalition work exposed the spatial dynamics of migration and the asylum process in Germany, and understand how racialized exclusions were experienced and challenged by refugees themselves. When I began talking to refugees, activists, and former East German residents in Brandenburg, the local landscape—including the forest, abandoned military barracks, regional infrastructure, and transport system—played a key role in people’s narratives about their daily lives. Living in legal limbo, without permits to work or travel, my interlocutors (many from urban Kenya) spoke of uncanny encounters in what they referred to as the “German bush.” While many German Berliners ventured out into these spaces in the countryside to explore “nature,” many refugees felt a sense of displacement and unease there. Narrating stories about the forest, my interlocutors drew attention toward the enduring ways in which colonial legacies, experiences of displacement, and racial exclusions shape and materialize in people’s relation to the landscapes they inhabit. Their stories thus challenged and refused popular and scholarly desires to depict the “real lives” (Steyerl 2001) of refugees as “case studies” and instead provided a glimpse of how landscapes—such as forests—are sites of nation-making, racialization, and exclusion that help shape what it means to become a “refugee” in Europe (Silverstein 2005; Stoetzer 2014). Yet their stories also showed how these very landscapes can become the grounds on which alternatives are forged.

As I continued conducting research in Berlin and its peripheries in subsequent years, I witnessed numerous contestations around “migration” and “nature” in the urban landscape as well. Whereas many refugees desired to live in the city and saw the Brandenburg forest as prison, others explored and cared for “urban nature” as a space of refuge from the city’s social divisions. At a time when much of the post-9/11 public discourse fixated on so-called “parallel immigrant worlds,” many Berliners rediscovered the city’s allotment gardens, established so-called multicultural gardens, or ventured out to search for urban wildlife. As I describe in the article, several city parks also became sites of contestation over the ways in which migrant communities related to the urban environment.

Observing these developments, I started tracking the disparate ways in which national formations, racial politics, and displacement shape how people inhabit “nature” in the city and its periphery—a question that I explore in more detail in my forthcoming book Ruderal City. In the book, I follow seemingly disparate communities, landscapes, and practices—and what I call “unexpected neighbors.” These range from encounters between botanists and plants growing in the rubble after WWII, to makeshift gardens cultivated by Turkish Berliners, to informal economies and “wild barbecuing” by Turkish and Southeast Asian migrants in urban parks, to the experiences of East African refugees living on former GDR military ruins in the forest at Berlin’s peripheries.

AED: You open the article with a description of Osman Kalin’s garden and tree house or gecekondu, an impromptu green space situated at the center of Berlin, as an example of how ruderal ecologies can take advantage of the gaps or “gray zones of the nation-state.” You later return to Osman’s dwelling to highlight how it serves as an important “space of hospitality for people, plants, and objects left behind” amid the relatively inhospitable social environment surrounding immigrants in Germany. What, if any, implications do ruderal ecologies like Osman’s gecekondu have on how we conceptualize racial, ethnic, and class inequalities at the national or international level?

BS: I think we can connect this question with the previous one about how my project evolved. As I mentioned, various encounters and conversations during fieldwork drew my attention to the ways in which racializing practices not only operate by marking bodies, but also the environments people inhabit. Donald S. Moore, Jake Kosek, and Anand Pandian’s (2003) notion of “race, nature and the politics of difference” became useful here because it refers to the myriad ways in which racialization practices work through ideas of “nature” and affect actual ecologies and landscapes. For example, in Germany, forests have played a key role not only symbolically in shaping national identity and racial discourse, but also materially in the creation of the nation’s economic power and racialized exclusions.

Working through different ethnographic stories such as Osman Kalin’s, my goal is to understand how national belonging, as well as racial and other forms of injustices, are tied up with and reworked in people’s affective attachments with place, with plants, and with other animate beings in the city. At the same time, the story about Osman Kalin’s gecekondu is also an example of how local actors resist social inequalities—by reshaping a city’s ecology to create spaces of hospitality.

The ruderal analytic foregrounds such practices and the ways in which they exceed and are more complex than existing analytical categories of “migration,” “nature,” or the “environment”—categories that are always also the product of administration, exploitation, and racialization. Ruderal practices emerge in imploded power structures and unsettle human efforts to domesticate the world. Through attention to more-than-human socialities, such as those enabled by the gecekondu, this analysis seeks to contribute to broader efforts in anthropology and the environmental humanities to expand our understandings of relationality and politics—and to trouble and rework analytical distinctions such as culture and nature, or the nation and its “others.”

AED: At the beginning of your article, you mention that conceptualizing infrastructure/technology and matter/ruins as separate objects of inquiry reproduces the nature–culture divide in anthropology. Could you elaborate on how a ruderal lens might re-imagine the role of technology in an urban context?

BS: As I point out in the article, recent ethnographies of infrastructure have offered important analyses of the relationship between ecology, technology, and culture. What is so exciting about an infrastructural lens is that it can shed light on the ecology and materiality of social life—by taking a close look at how new forms of governance are renegotiated via built environments and technological networks. At a moment when climate emergencies, species extinction, displacement, and loss of livable habitats confront human societies with the limits of capitalist modes of extraction and “growth,” it is particularly important to also map the instabilities, ruinations, and unintended effects of human design. Yet with the ruderal lens, I suggest that we may be able to shift attention away from a binary focus on instabilities/ruination (of “matter”) on the one hand and the structure of technology, culture, and infrastructure on the other—and to instead ask: How do infrastructures reassemble people’s connections to each other and to the world? My concern is that infrastructural engagements may run the risk of concentrating too narrowly on material structures and networks (their stability or instability), rather than orient themselves toward embodiment, dispossession, and the broader social worlds that are exposed to social injustice. A ruderal analytic instead aims at cultivating modes of attention that capture the “unexpected neighbors” alongside built structures and their inherited histories of labor, extraction, and power. Through attention to the lives that fall by the wayside, how can we detect new possibilities for connection and for reassembling the social?

This is both a matter of method and strategy. In her essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Ursula K. Le Guin (1989) reminds us of the Greek etymology of technology and the broader meaning it signifies: the science of craft. Technologies encompass a set of skills and methods through which we make things and engage with the world. These can also include practices such as growing, collecting, and gleaning. Critiquing the destructive effects of capitalism’s extractive technologies from a feminist perspective, Le Guin cautions to not reproduce what she calls “the killer story,” but to instead expand our methods and what we frame as technology. That’s why I think it’s important to not only focus on pipes, roads, canals, or other material networks in infrastructural engagements, but to also consider seemingly insignificant things like gathering leftover objects, scattering seeds, or describing plants pushing out of the cracks of sidewalks. It is about identifying specific instances in which living beings ally in unexpected ways and are determined to reconnect across difference—with open-ended outcomes.

AED: In the article, you describe the Anthropocene as “a universalizing framework” that often flattens the kinds of connections central to ruderal worlds. It made me wonder whether the analytic of ruderal ecology might act as its own ruderal element within contemporary anthropological theory. That is, would you describe “ruderal ecology” as emerging from the cracks of the current rupture in our own social fabric?

BS: That’s a wonderful question. I am addressing this more deeply in the forthcoming book. As I also point out in the article, anthropology these days seems to be a “science” of ruins, examining life on an increasingly inhospitable planet. Yet in a way, anthropology has long grappled with various forms of ruination. The field emerged amid the ruins of colonialism and racism, chronicling the heterogeneity of life amid vast destruction.

In conversation with the work of many other feminist scholars, I am interested in exploring the following question: what might cultural critique look like today in these times of rubble? Too often, contemporary debates about social and environmental “crises”—including debates about the Anthropocene and climate change, or the recent so-called “migration crisis”—seem to forget previous feminist and antiracist critiques and sideline or appropriate scholars of color that have already provided powerful analyses for decades. I think the challenge is thus also to ask who connects with whom and what bodies will matter as people engage current political formations and planetary futures? The focus is then less on heterogeneity amid destruction in the Anthropocene, but on joining a broader conversation about how anthropology can be accountable and build solidarities across injustices. In other words: how to create ethnographic and political work that is not extractive?

AED: This article stems from your larger book project, Ruderal City: Ecologies of Migration and Urban Life, which explores the “changing cultural politics of nature and citizenship” in Berlin. Can you discuss how this article fits into your broader research agenda? And finally, what does your future scholarship look like?

BS: Yes, the article gives a glimpse of the material that I work through in Ruderal City. The book is based on more than ten years of ongoing fieldwork with a wide range of communities, including migrants and refugees, as well as environmentalists, ecologists, nature enthusiasts, and other urban residents in Berlin and its peripheries. I argue that beyond a present-day media or scholarly focus on the suddenness of a “migration crisis” in Europe, there is yet another story to be told. In Germany, this story leads us into the thickets of its forests and a range of landscapes in which the contours of the nation and Europe are reshuffled. Looking across different landscapes—from urban wastelands, to gardens, forests, and parks in Berlin and its fringes—I examine how racial and other social inequalities are reconfigured in conflicts over human relations to the urban environment. Attending to these conflicts, the book thus also exposes the less visible effects of displacement and inhospitality in the middle of Europe that have long been in the making—and that have more recently erupted again onto the political landscape.

In regards to your question about future plans, I have begun to work on a new project on wildlife mobilities, climate change, and nationalism in Europe and North America. A language of invasion and unruly nature has reentered the political arena in the global north in recent years (see also Hage 2017; Ticktin 2017)—at a time when migrants and refugees, not only symbolically but also through actual policy making and everyday practices, are systematically dehumanized. In this project, I explore how more-than-human mobilities and approaches to manage these become deeply entangled with border politics, race, and the shifting role of the nation state today.

One of my sites for this project includes ongoing debates about wild boar and their role in recent outbreaks of the so-called “African swine fever virus” (ASFV) across Eastern Europe and Asia. Following the course of this disease, I am interested in how strategies of containment of the virus that first emerged in a colonial context pose challenges to EU agricultural policy and local decision making at a time of rising nationalist sentiments, national border securitization, and political fragmentation.

Acknowledgments

Bettina Stoetzer would like to thank Nishita Trisal and Jason Alley for feedback on the interview.

References

Gelbin, Cathy, Kader Konuk, and Peggy Piesche. 1999. AufBrüche: Kulturelle Produktionen von Migrantinnen, Schwarzen und jüdischen Frauen in Deutschland. Königstein: Ulrike Helmer.

Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Encarnación, and Hito Steyerl. 2003. Spricht die Subalterne deutsch? Migration und postkoloniale Kritik. Münster: Unrast Verlag.

Hage, Ghassan. 2017. Is Racism an Environmental Threat? Malden, Mass.: Polity.

Hügel-Marshall, Ika. 1993. Entfernte Verbindungen: Rassismus, Antisemitismus, Klassenunterdrueckung. Berlin: Orlanda.

Le Guin, Ursula K. 1989. Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places. New York: Grove.

Moore, Donald S., Jake Kosek, and Anand Pandian, eds. 2003. Race, Nature, and the Politics of Difference. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Nghi Ha, Kien. 2010. "Integration as Colonial Pedagogy of Postcolonial Immigrants and People of Color: A German Case Study." In Decolonizing European Sociology: Transdisciplinary Approaches, edited by Encarnación Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Manuela Boatca and Sérgio Costa, 161–78. Burlington: Ashgate.

Oguntoye, Katharina, May Ayim, and Dagmar Schultz, eds. 2007. Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte. Berlin: Orlanda.

Silverstein, Paul A. 2005. "Immigrant Racialization and the New Savage Slot: Race, Migration, and Immigration in the New Europe." Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 363–84.

Steyerl, Hito. 2001. "Europe’s Dream: A Documentary Film Project." Translated by Tim Jones. Springerin 2001, no. 2.

Stoetzer, Bettina. 2004. InDifferenzen: Feministische Theorie in der antirassistischen Kritik. Hamburg: Argument-Verlag.

———. 2014. "A Path through the Woods: Remediating Affective Landscapes in Documentary Asylum Worlds." Transit 9, no. 2.

Ticktin, Miriam. 2017. "Invasive Others: Toward a Contaminated World." Social Research 84, no. 1: xxi–xxxiv.