Rivers to the People: Ecopopulist Universality in the Balkan Mountains

From the Series: Green Capitalism and Its Others

From the Series: Green Capitalism and Its Others

After they had exhausted other opportunities for cash and foreign capital, the state regimes in the Balkans started to target natural resources as the next “wealth of nations” to be privatized (Poenaru 2014). Such is the pan-regional initiative to create 3,500 small hydropower plants, a nominally green technology meant to capitalize on Europe’s last "wild rivers" to boost renewable energy sources, in line with the Paris Climate Agreement. But while being carbon-free, small hydropower plants (SHPPs) make an unprecedented frontier for elite enrichment and environmental spoil. They do not use impoundment (dam types), but derivation, which means channeling rivers and streams into pipes. This depletes fish and wildlife, dwindles cattle and irrigation supplies, and interrupts subterranean flows, posing risk for urban water reservoirs. Producing minimal electricity—their full construction would fulfill only two percent of national grid demands—the profits Balkan SHPPs yield are mainly speculative, as electricity users finance state subventions for private investors. And while EU banks buddy up to credit the development, its execution involves local party connections, ignored communities, and a brush with violence.

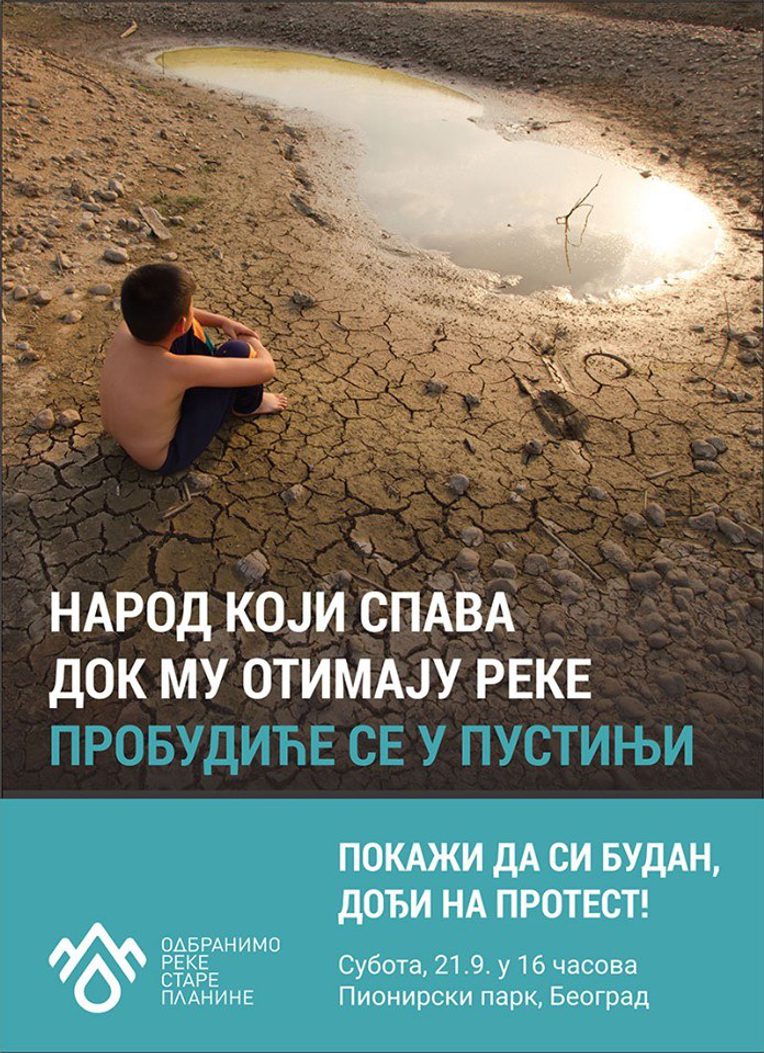

From Bulgarian fishermen to Montenegrin cyclists, Albanian villagers, and Serbian mountaineers, mass grassroots movements formed against the MHPPs. While these are independent groups, they have a few commonalities. First, they emerge as motley alliances—of affected villagers and their urban kin, ecologists and nature lovers, and a wide chunk of the citizenry mobilized through online platforms. Second, the struggles stay localized: while there is a lot of collaboration, specific groups defend particular rivers and river regions. Third, the “river guardians” present themselves as going beyond politics to defend “life itself.” Mobilizing the vitalist imagery of water as a source of life (Muehlebach 2017), they portray their actions as in alliance with a higher authority of “Nature,” one that trumps earthly powers. And with an efflorescent folklore and calls for “battle until death,” the movement increasingly opposes “the people” against the state and the capital. In the Bosnian village of Kruščica, local women barricaded a bridge for more than a year until the construction was called off. In Stara Mountain in Southeast Serbia, villagers returned the Rudinjska river to its original riverbed, declaring a “water war” against the investors. But exactly what “people” are being summoned here?

Although they interweave the languages of nation, citizenship, and class, the river guardians can be reduced to none of the above. Instead, water here functions as what Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe (1985) called an empty signifier, a nexus in creating an alternative universality. For the two, populist mobilization starts from no essential entities, such as ethnicity or class. Rather, “chains of equivalence” are formed between different groups who find a common enemy to fight and a common sense to gather around (Laclau 2005). In this light, Balkan river guardians read as a part of the wider wave of contemporary ecopopulisms: environmental struggles that start to generalize other social frontlines. Under the umbrella of “life itself,” ecopopulism allies a plethora of social actors with disparate meanings, affects, and demands. But, differently from Laclau and Mouffe’s model, life is not merely the stuff of signs. Its equivalences are made in living webs and cycles, in an intergenerational moral ecology connecting the dead, the living, and those still to be born. And if the Balkan rivers came to be the basis of new insurgent kinship, it is because they could be imagined as the last shared substance, at once traversing different species, places, and times.

First of all, Balkan ecopopulisms are about (de)population. As rivers flow fastest in mountain areas, where population is depleted and the aging villagers subsist on agriculture and pensions, SHPPs have an impact on peripheral areas, borderline populations, and groups excluded from the mainstream politics. These in turn come to symbolize the demographic panic that haunts regional politics more generally (Blagojević-Hughson and Bobić 2014). A common belief South Serbian “river guardians” express, for example, is that various state regimes in the past had urbanized the population to facilitate a water grab in the hinterlands. They interpret the riverine “biological minimum” as the harbinger of the “population minimum,” a systematic squeezing out of all life from the country. Trout, crabs, and other nonhuman subalterns (Howe 2019) get portrayed as the suffering companions of aging peasants, un(der)employed urbanites, and their (un)born children, inasmuch as they are all left voiceless and waterless, to die out. To this vision of an actual degrowth, the movement shouts: first we defend the rivers, then we revive the mountains.

Second, population is about generation. As SHPPs mean enclosing water commons, guardians can only do as much when evoking land possession rights. Rather, they have to describe the rivers as “neither yours nor ours,” something inherited from the previous generations (ancestors, Nature, partisan struggle) to be saved and passed on to the future ones. This obligation to transmit and “the rhetoric of descent” (Rutherford 2013) feature heavily in social media and street protests, where grandparents say they defend the rivers for their grandchildren, and toddlers feature as mascots. Aging mountain militants are thus contemporaries of youth climate strikers (Brewster, this series); both recenter politics in wider chains of interdependence beyond one’s time.

But alas, Higher Goods live in earthly claims, and it is precisely the current interests that make the movement so generative. For it is not only the investors who find speculative opportunities in the river flows. They attract all sorts of fishing and mountain hobbyists, who want to continue enjoying natural riches; those with a piece of land, who dream of eco-tourist businesses; and above all, all those who equate “free rivers” with “free people,” a symbolic break from the bondage of precarious work and an authoritarian state. At times, it is precisely this heterogeneity that spills over, and antagonisms start to bubble under the veneer of a united fight. Do we protect some or all rivers? Prioritize this or that village? Fight against the capital, or try to channel it into projects friendly to locals? Get into the party politics or not? That antagonisms exist shows that the movement is political, not that it fails. Rivers unite as well as divide.

The problem with Earth, Bruno Latour (2019) reminds us, is that it is at once too big and too small. It is too small for capitalism’s eternal growth, and yet “too large, too active, too complex, to remain within the narrow and limited borders of any locality whatsoever” (Latour 2019, 16). The future of socio-environmental struggles will depend on their ability to scale their focus up and down the ladders of planetary abstraction, before and beyond the present time. Also, on their preparedness to articulate clear social frontlines in such scale-making, without resorting to the assumed neutrality of “life itself.” The fight for life must not become depoliticized.

Blagojević-Hughson, Marina, and Mirjana Bobić. 2014. “Understanding the Population Change from Semi-Peripheral Perspective: Advancement of Theory.” Zbornik Matice Srpske za društvene nauke 148: 525–39.

Howe, Cymene. 2019. “Greater Goods: Ethics, Energy, and Other-than-Human Speech.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 25, no. S1: 160–76.

Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and the Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

Latour, Bruno. 2019. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity.

Muehlebach, Andrea. 2017. “The Price of Austerity: Vital Politics and the Struggle for Public

Water in Southern Italy.” Anthropology Today 33, no. 5: 20–23.

Poenaru, Florin. 2014. “The Wealth of Nations: Nature as Capital and Eco-Criticism as Anti-Capitalism.” FocaalBlog, July 17.

Rutherford, Danilyn. 2013. “Kinship and Catastrophe: Global Warming and the Rhetoric of Descent.” In Vital Relations: Modernity and the Persistent Life of Kinship, edited by Susan McKinnon, 261–81. Santa Fe, N.Mex.: School for Advanced Research Press.