The film Gods and Kings has been taken down. The trailer, interview with filmmakers, photo essay and resource materials will still be live. Thanks for joining us!

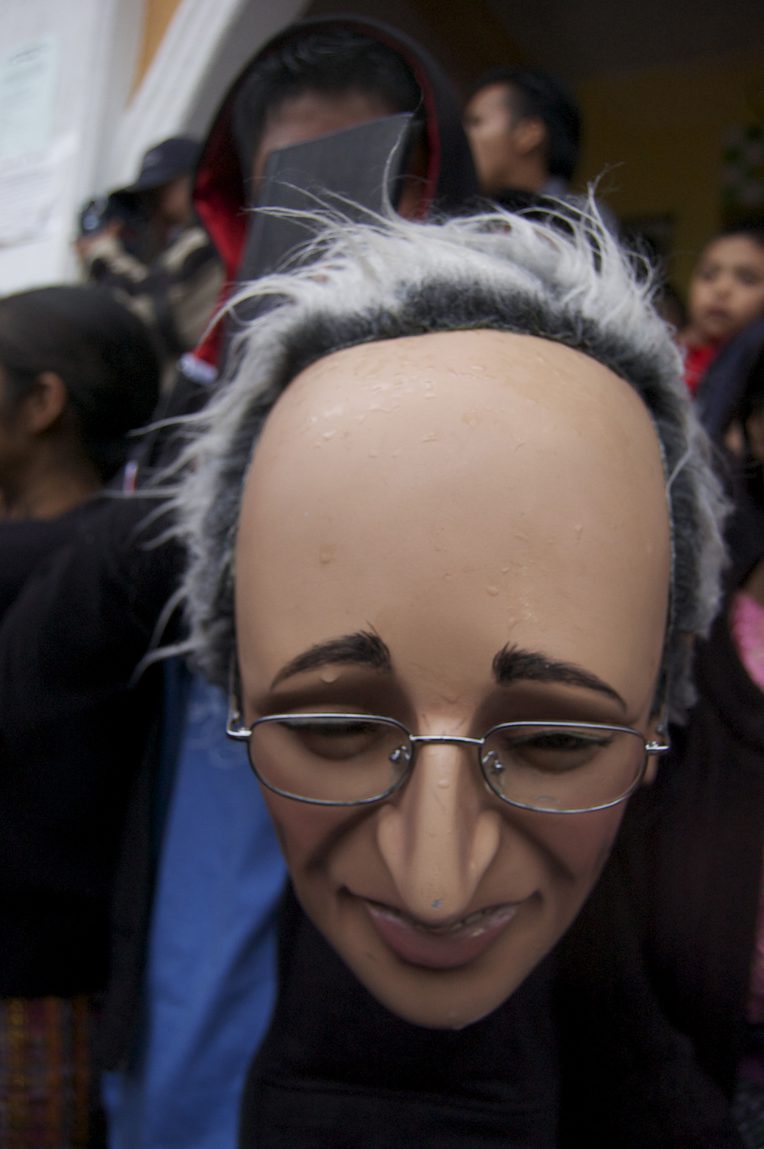

For the next two weeks we are thrilled to share the documentary Gods and Kings, a feature film by Robin Blotnick and Rachel Lears. Gods and Kings is a fascinating and visually striking film about the unique Disfraz dance in the predominantly Maya town of Momostenango, Guatemala. Unlike other traditional folkloric dances, pop-culture icons like Xena Warrior Princess, the Chucky doll and political figures like Ríos Montt and Obama are central caricatures of the dance. Costumes are locally produced and masks are blessed in shaman altars before the dances begin. An absorbing exploration on the globalization of images, Gods and Kings observes the ways in which media images and global politics are re-imagined and take on new meanings as they become part of the Maya cultural practices and belief system.

Along with the film, we have an interview with the filmmakers and their collaborator, Ronda Taube, an art historian at Riverside City College. The conversation speaks to the process of filmmaking, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the politics of the Disfraz dance and globalization. We are also excited to present a portion of a photo-essay on the Disfraz dance by Rachel Lears. As always we have a study guide with additional classroom-ready content.

Synopsis

In the muddy market square of Momostenango, Guatemala, where shamans burn offerings in the shadow of the Catholic church, a bizarre spectacle is arriving. Horror movie monsters jostle through the crowd, followed by Mexican pop stars, Japanese game avatars, and dictators from the dark years of the 1980s. Unlike the folkloric performances long studied by anthropologists, the new Disfraz dance won’t show up on any postcard. In some villages, it’s even been banned for the way it frightens tourists. So how did these fiberglass masks of Xena: Warrior Princess come to be blessed in the smoke of Maya altars? Gods and Kings is a film about a little town in the mountains and the great empire to its north, a story of conquistadors, tricksters, sorcerers and advertisers. In a town where Chucky from Child’s Play is a real evil spirit that appears in people’s nightmares, stories are a serious business, and it always matters who’s telling them.

Biography

Robin Blotnick, Writer, Director, Editor. A product of backwoods Maine, Robin has worked in motion picture development, and as a freelance editor of everything from anarchist propaganda to celebrity home movies. His first documentary,Chocolate Country, a portrait of the work, lives and music of Dominican cacao farmers, received a Grand Jury Prize at the Seattle International Film Festival.

Rachel Lears, Writer, Producer. Rachel’s feature documentary Birds of Passage (2010), has circulated in international film festivals and toured Uruguay for the Ministry of Education and Culture. Her video art pieceEthnography of No Place (2008, with artist Saya Woolfalk) has screened at galleries and museums worldwide. She also holds a PhD in cultural anthropology.

Robin and Rachel are currently in post-production on The Hand That Feeds, about an undocumented immigrant sandwich maker who sets out to end abuses at a New York City bagel shop and ends up making history.

Interview with Robin Blotnick and Rhonda Taube

Patricia Alvarez: How did you first encounter the disfraz dance and how didthe idea for the film emerge? What was your initial reaction to seeing the disfraz dance?

Robin Blotnick: I heard about the Disfraz from a former roommate who had taken a class with the scholar Rhonda Taube. At the time I was plotting a documentary about cargo cults in the South Pacific, and I thought this dance would allow me to explore similar themes. Plus Guatemala was a lot cheaper to get to from New York. When I flew down to scout out the town of Momostenango in November 2007, I didn’t expect to actually see a Disfraz until the following summer. But as luck would have it there was a small neighborhood festival happening the day I arrived. A marimba band was set up on a dirt road, blasting distorted music through these massive speakers, while seven pairs of dancers shuffled around in the hot sun. I found it weird and wonderful and a bit creepy. These familiar images had been transformed into something utterly new, and I wanted to learn more.

Rhonda Taube: My first trip to Momostenango was during the summer of 2002 and it was the firsttime I had ever seen the disfraces. It was feria, or festival time, and l was looking fora cultural experience so I followed a very large crowd to see what was the attraction. I was hoping for a Dance of the Conquest or some traditional dance that I could write about for my doctoral thesis. Instead, what I happened upon was a dance of Osama Bin Laden and Hillary Clinton. The costumes were so exact and stunning that all of the characters were easily recognizable. Now bear in mind, this is just about 10 months after September 11, so the whole experience completely blew me away. Nevertheless, the audience’s response fascinated me as well; everyone was stone faced and just staring, not clapping, smiling, or dancing along. The performance was entirely not what I had expected to find. I immediately had a number of questions swimming in my head regarding Third World commentary of First World (my) culture. I knew right away that I wanted to study these dances and find the underlying cause of what was transpiring before my eyes.

Patricia Alvarez: Central to making the film was a close collaboration between filmmakers and scholars. How was this process?

Robin Blotnick: I’m not an anthropologist—I’ve never been to grad school at all—and I couldn’t have made the film without the help of the North American scholars who study in Momostenango. Besides the missionaries and Peace Corps volunteers and the occasional blanket-shopping tourist, anthropologists are the only gringos who visit Momostenango, but there have been a surprising number of them, starting with Robert Carmack in the 50s. I started out by reading Garrett Cook’s book Renewing the Maya World, which gave me a great window into the religious life of the community. Later I interviewed Garrett, along with other North American scholars, particularly Maury Hutcheson and Rhonda Taube. All three became friends and traveling companions and close collaborators on the film, sharing what they’d learned from years of field work. Later I met filmmaker/ anthropologist Rachel Lears, who became the film’s producer (and now my fiancée), and her perspective was integral as well. As someone well-versed in contemporary anthropology, she confronted me to challenge some of my own motivations in making this film and to move beyond the sort of exoticist tropes westerners often resort to when depicting the Indigenous.

Rhonda Taube: If I can chime in here, I’d like to say that although Robin never set out to make an ethnographic film, that’s exactly the result. And it just happens to be excellent. Robin always approached the project like a scholar and I think that’s why the collaborationwas seamless.

Patricia Alvarez: How did you obtain access to the community, the shamans and to document belief practices?

Robin Blotnick: When I arrived in town, anthropologists and scholars had already done much of the hard work of acclimating the community to outsiders with cameras. That said, dancers and shamans were suspicious of people exploiting their image without paying something for it. This was savvy on their part, and perfectly fair, so I always donated as much as I could afford to—which wasn’t much, but enough to show respect—to the dance troupes and the cofradías or religious fraternities. After a solemn consultation with leaders stating our intentions and an offer to collaborate financially, we were usually given access to everything we wanted to film. The more traditional dancers were particularly glad for the attention, because they felt that their art was underappreciated. As much as the belief system in Momos depends on the preservation of “secrets,” the performers and shamans in this community feel they are performing rituals on behalf of the entire world, and they wanted the world to know about it. I also made a point of hiring local Maya priests to do ceremonies asking the local spirits to protect us and our project. This helped build relationships with local spiritual leaders, but it also made me feel a whole lot safer.

Rhonda Taube: I just showed up in town, stayed for a while, and kept returning. People in Momostenango are quite familiar with the States and have a custom of hospitalitycombined with an affinity for North American culture. Many people in Momos have family currently living in the States or have lived in the US, themselves. I travelled there 3 times before I spent a summer (2005) living with a family that the Peace Corps volunteer at the time helped me set up. Once I became somewhat known in town and kept returning, the rest fell into place. When Robin arrived in town, being part of a film crew brings a certain cachet that also opened many additional doors with community members.

Patricia Alvarez: How was the process of filmmaking and sound recording during the dances? Can you discuss filmmaking and other production/war stories?

Robin Blotnick: This was my first feature film, and I made a lot of rookie mistakes. Thankfully I was able to borrow money to bring a crew to town, including an experienced TV shooter/producer, Elyse Neiman, who kept things semi-professional as much as possible (even when dodging a falling tree, which you can see in the film). For the most important days of the festival we had two cameras running around, often in opposite directions, trying to suck up every interesting thing happening around us. But things happen on a schedule all their own in rural Guatemala, and misinformation was rampant, so we were often chasing false leads. We ended up with hundreds of hours of great footage, but no clear story, which is why I had to come back the following summer and get more content.

Patricia Alvarez: Seeing all the characters from horror films and politicians is very visually striking. Why the appeal of these particular characters, specially ones like Chucky and predator? How do these characters come to inhabit sacred Maya beliefs?

Robin Blotnick: In the film, one of our subjects, a traditional dancer, tells us that things like Chucky can sometimes appear in this town, in real life. Indeed, he says “everything you see in the movies can happen in real life here.” For people steeped in the syncretic costumbre tradition, the spirit world is ever-present, and there’s no reason to believe a creature like Chucky, who is capable of appearing in our nightmares and seizing control of our imagination, isn’t real. The fact that Chucky, in the movie Child’s Play, is a mass-produced plastic toy that is brought to life through sorcery is particularly interesting, because you could argue that’s in essence what the Disfraz dance is doing.

In Predator, Arnold Schwartzenegger’s character is an American green beret on a CIA black op in the Guatemalan jungle. For a Guatemalan, I’d imagine, this 1980s backdrop gives an extra gravity to what is otherwise a schlocky sci-fi film. The anthropologist Diane Nelson speculates that Guatemalans are especiallyattracted to horror movies because they help process the trauma of the horrific genocide of the 80s, where many acted as both victims and victimizers.

Rhonda Taube: Okay, first, I want to clarify that Chucky and Predator are absolutely not the focus ofworship by contemporary K’iche’ Maya people today in any context. Their costumesare fantastic, expensive, and incredibly creative features of a civic-religious celebration that exhibits the piety and spiritual devotion of the individual wearing it.

Next, there is certainly not one homogenous understanding of traditional Maya dance and there positively is a variety of understandings of the disfraz dance, primarily depending on one’s age, economic situation, and social class within the community. On one level, there are numerous characters that appear in mass media and contemporary pop culture with some frequency that have been reconfigured for the purpose of attracting young people to the dance. Yet, underlying this basic component is a tension of recognition, a feeling of belonging that permeates those who know who the characters are and elevates them within the community. What I mean by this is that many people in the audience during the dance, especially from older generations, do not recognize most, if any, of the characters and are merely present for the spectacle. In addition, sometimes not only audience members do not know who the costumed characters are, even the performers themselves are unfamiliar with the myriad personalities that appear. For example, after the Primer de Agosto group performed in 2008, two of the participants asked me if I could explain the characters from their costume, Harry Potter and Hermione. They were at a financial level high enough to afford the hefty fees that costume rental and group membership incurred, but still they were not entirely linked to or aware of contemporary US cinema. So, on the one hand the costumes mobilize a particular faction of Momostenango society as culturally savvy, on the other hand, it is still nonetheless a diversion meant to fun and provide outrageous entertainment.

Patricia Alvarez: How are these characters transformed, as they become part of the dances? What aspects of the disfraz dances differ from traditional ones and in what ways is it still linked to them?

Robin Blotnick: I think what often happens is dancers find an image they like on the internet, print it out and bring it to the costume makers. The costume makers then take liberties with the original idea, and it evolves into something new. In the Disfraz, dancers can never wear the same costume twice, so there’s a lot of demand for fresh creations. As the years go by, masks and costume elements get recombined to create new characters. I’ve seen Wonder Woman’s head on the body of a Brazilian carnival dancer, and the head of a Dothraki from Game of Thrones on a Samurai body. Rhonda has pointed out that dancers can create characters in a modular way, the way players create their avatars in video games.

The main difference between the older dances and the Disfraz is that the older dances tell stories. They’re really works of dance-theatre, with complex roles and scripted dialogue. With the Disfraz, the dancing is monotonous and simple. The costumes are the main appeal. Traditional dancers are actively seeking to recreate the past, to banish all modern influences from their art form. The Disfraz seeks the exact opposite, novelty and constant change.

But both types of dances are sacrifices that honor the patron saint of the festival and bring protection and blessings to the entire community. Dancers are motivated by religious feeling and a sense of local pride. Typically traditional dancers are subsistence farmers from the outlying villages, with more time than money to devote to their saint, and Disfraz dancers are more middle class Maya from the town center, who have less time because they work for wages, but more money to spend on flashy costumes.

Rhonda Taube: One of the obvious ways in which the characters transform during the dance isthrough their complete removal from their original context as a cartoon character, athlete, political figure, or TV star. Our American sense of corporate logo or “branding” is utterly dropped. That is why Barack Obama may be seen dancing next to Daddy Yankee, Buddha, and Pamela Anderson as Barb Wire. In this sense they activate the difference within the community of those “in the know” and those outside of the cable, internet, smart phone generation. In this way, they really create the recognition of a leisure class within the community, those who have the funds and the time to surf the net, play video games, and watch cable television. Yet, underlying the social opposition is a very Maya understanding of the importance of public performance to celebrate and indicate religious affiliation. The organization of the hierarchy within the dance groups is modeled on the indigenous cofradia system, the religious brotherhood responsible for festivals. In addition, many of the rituals of preparation the dancers undergo, such as a calendar cycle of prayers, abstinence from sex and alcohol, as well as other customs, is quite similar to what the participants traditional dances undergo. The main differences, aside from the costumes, are the narratives traditional dances, as well as the secrecy. What I mean by secrecy is that traditional dancers guard their identities from the public and do not reveal themselves as individuals. The disfraces dancers, on the other hand, publicly remove their masks for individual credit and increased social respect. This reveal, or “discovery,” is indeed the most exciting moment of the performance. I suspect this is so not only for recognition, but also because not much else really happens. The dances are quite monotonous and again, tell no story.

Patricia Alvarez: Can you expand on how US politics and media are appropriated into the dances? Can you comment on the ways in which Guatemalan and Mayan identities are being imagined in relation to the US?

Robin Blotnick: The US is not the only foreign influence on the festival. Mexican personalities are huge, and increasingly there’s a lot of Asian influence, from smiling Buddhas to anime superheroes. But the US looms large, and one of the main reasons for that is that so many Maya from the highlands have migrated here over the years—a process that began with refugees fleeing the genocide of the 80s. Those who complete the heroic, dangerous passage through Mexico and over the border would send money home, and also toys and videos and other cultural trappings, and the US began to play a big role in the imagination of those who couldn’t make it here themselves. Showing your familiarity with US culture became a point of pride. After the peace agreements, foreign investors began to swoop down on the country and the influence of US consumer culture became really strong in towns that had previously been more cut off from the larger world. Rhonda has pointed out that the festival dances in Momostenango were always about otherness in some form. With the Disfraz dance, outside cultural influences that might otherwise seem threatening or invasive are captured and reclaimed by Maya artists. It’s kind of the same process that happened with Spanish and Catholic influences back in the days of the Conquest. The Maya are transformed, but they’re actively transforming too.

Rhonda Taube: The US has meddled in Guatemalan politics and society for a long time and the average Guatemalan is quite aware of our government’s outward and covert interventions. Although the US’s actions rarely helped indigenous Guatemalans, they do have a fascination with our culture. Despite our sordid history in Central America, many Guatemalans still want to work in the US. As I mentioned earlier, many indigenous Guatemalans have family living here, or have lived here previously. US corporations are the colonizers of Guatemalan society today, though international franchise businesses on Guatemalan soil or via cultural remittances between family members returning from the US. The US dominates process and product.

One of the reasons so many indigenous Guatemalans seek employment in the US is because they say they have no prospect for upward mobility in a country that the minority of citizens/dominant culture controls. The power of the dominant “Ladino,” that is, non-Maya culture, derives specifically from their ability to be non-Maya. The US, therefore, is a haven from the rigidity and friction of a racialized society that discriminates against the indigenous populations. Moreover, the dominant culture originally founded the disfraces as a way to distinguish themselves from the Maya and connect themselves to Latino populations in North America. I’ve always found it ironic that it’s their racism that drove the Maya to look for opportunities elsewhere and have allowed them to remake themselves the true trans-nationals. They have the actual, physical connections to the US that Guatemalan dominant culture claims. Thus, in this way, the disfraces are a political dance of identity and nationalism played out with the US as both an archetypal backdrop and terrestrial reality.

Patricia Alvarez: The costume shops are fascinating and important places for the dances. Costumes are made almost artisanally. Can you expand on them and your experience filming there?

Robin Blotnick: Yes, it’s really cool to see these artists take images that are mass-produced in the US and recreate them as these meticulously crafted artisanal objects. It’slike this perfect reversal of the way culture usually goes under capitalism. The costume makers were a lot of fun to interview, and their work is mesmerizing. My favorite moment was when one of them told me and Rhonda that the film Apocalypto, which presents a US fantasy of the ancient Maya as monstrous and bloodthirsty, was quite historically accurate. As a modern Maya he seemed totake some pride in how terrifying and violent his ancestors had been. It was justone of those moments that turns all your expectations on their head. Later I came back and bought some masks from these same artisans, to give to our most generous Kickstarter supporters. Rachel and I kept one pair for ourselves and they’re hanging in our living room right now, looking down on us with their dead fiberglass eyes.

Rhonda Taube: Yes, the costume shops are incredibly fascinating! This really is a boom business in the highlands right now. The exponential growth of costume shops is certainlyone unique outcome that I hope to follow closely over the next few years. The first time I went to Santa Cruz del Quiche to visit the costume shops was with Robin. Atthat time, 2008 I believe, there were only a couple of storefronts manufacturing the costumes. Now, there are at least a dozen as well as a number of private families that rework and recycle used costumes for rental. That’s in Santa Cruz alone. I plan to return to Totonicapan to see if the businesses have developed in a parallel manner.

The costume shops really are the driving force and creativity behind the dances. They find the inspiration for the costumes from TV and the Internet, as well as from their own imagination. Although there is such an emphasis on characters from mass media, the costumes are still all hand made. The shop owners make the masks and basic costume elements from a fiberglass mold, but they hand model the features in putty and individually hand-paint the faces. This is taking an element that is mass created (Shrek, for example) and craft a unique mask outside of the typical field of production. Again, the shop owners clearly modeled their storefronts on something that already existed in Guatemala society called a moreiria, a traditional dance rental shop. Like the comparison of the cofradias to the disfraz dance groups, the moreiria provided a structure that underlies the business practice. In this way, the costume shops are still very “Maya.”

Patricia Alvarez: I’m interested in the role of women in the dances and the female characters that become popular. How has the role of women changed and why those particular characters?

Robin Blotnick: Rhonda has a lot more to say on this than I do, but I believe she’s discovered that the Disfraz Femenino started in Quiche province in a town that had lost most of its men in the 80s conflict. The women felt they needed to step up and fill the men’s role, and their dance has since spread to many other towns. The traditional dances forbid female participation—men play the female roles like in old Shakespearean theatre. But the Disfraz is relatively new and able to reflect changes in the community. The costumes are mostly inspired by the show Xena: Warrior Princess. The dancers seem to like her because she’s sexually confident but also strong enough to defend herself. For Maya women who are used to wearing traditional long wool skirts and woven blouses, it takes guts to dance in front of your whole town in a miniskirt and knee-high leather boots. But they do it as part of a communal religious ritual, so it doesn’t read as a transgression.

Rhonda Taube: This is the subject of the book I’m currently working on tentatively titled “Quetzal Flower Meets Xena Warrior Princess: Performances of Gender, Social Class, and Religious Devotion in Momostenango, Guatemala.” In the book-length study, I’m exploring this very theme, the changing lives of women in Momostenango. I think the dances both help push the envelope for women and reflect changes that have already taken place in the post-war society of the highlands. As far as Guatemala’s indigenous communities are concerned, Momostenango past is unique in that the men made their living as traveling salesmen. By necessity women had to be educated, which meant speaking Spanish, reading some, and knowing some basic math and accounting. This allowed women to competently run the retail shops at home while the men were away. In turn, the women became very cosmopolitan. However, women are still institutionally prevented from participating in public office, despite such role models as Rigoberta Menchu Tum.

Today, I know many women who participate in the Segundo de Agosto disfraz group in Momostenango that have also taken control of their own lives. For whatever reason, whether choice or circumstance, they are without men and are no withering daisies. They have strong personalities, their own incomes and expendable resources, and want to demonstrate their independence publically by participating in the disfraces. They have computers in their homes, smart phones for texting, and profile pages on Facebook. My fieldwork no longer requires me to be in Guatemala, we communicate through Skype and email on a regular basis. The types of characters they choose to perform as suggests they are also asserting control over their sexuality. Cleopatra, Xena, Barbarella-type figures all highlight powerful women with sexual appeal and appear replete with lots of revealed flesh. The costumes are sexually appealing and clearly arouse desire, as married women with husbands are less likely to participate. These are the most popular of all the dances and attract the largest crowds. While many of the men’s groups struggle financially, the women’s group seems to be just fine. They excel at balancing their books!

Patricia Alvarez: What films and other resources served as an influence for Gods and Kings?

Robin Blotnick: One major influence that will be obvious to those familiar with his work is Adam Curtis, the BBC filmmaker. Not only did I lift his playful archival montage style for the historical segments of the film, I was also inspired by the section on Guatemala in The Century of the Self, which shows how public relations wizard Edward Bernays helped set the stage for the US coup in 1954. Jean Rouch was also a big influence. He developed the idea of “cinema verite” which doesn’t mean “fly on the wall”, like many Americans came to interpret it, but rather “fly in the soup”—interacting with and playing with reality, acknowledging your own subjectivity and all that. It was important to me in making this film to show the curiosity moving both ways, to show Momostecans observing me while I observed them, and sometimes even confronting the camera. For better or worse, Curtis and Rouch also inspired me to make use of voice over, which is very unfashionable in US documentary circles.

As far as books, I got a lot out Michael Taussig’s The Devil and Commodity Fetishism (though I can’t say I was able to fully understand it), and Fables of Abundance

by Rachel’s father Jackson Lears was a huge inspiration for the

sections about advertising and marketplaces. There are many others too,

and there’s a full list in the end credits if anyone is interested.

Photo Essay by Rachel Lears

On dance

References

Cook, Garrett W. 2000. Renewing the Maya World: Expressive Culture in a Highland Town. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Mendoza, Zoila. 2000. Shaping Society Through Dance: Mestizo Ritual Performance in the Peruvian Andes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nájera-Ramírez, Olga, Norma Cantú and Brenda Romero, eds. 2009. Dancing Across Borders: Danzas y Bailes Mexicanos. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Nelson, Diane M. 2009. Reckoning: The Ends of War in Guatemala. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press.

Offit, Thomas A. 2010. "The Death of Don Pedro: Insecurity and Cultural Continuity in Peacetime Guatemala" Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 15, no.. 1: 42–65.

Taube, Rhonda. 2013. “Visualizing Identity in the 21st Century Guatemalan Highlands: New Directions in K’iche” Masked Performance." In Indigenous Religion and Cultural Performance in a New Maya World, by Garrett Cook and Tom Offitt. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

———. 2012. “Manufacturing Identity: Masking in Postwar Highland Guatemala.” Latin American Perspectives 39, no. 2.

Taussig, Michael. 2010. Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Thomas, Kedron. 2013 "Brand "Piracy" and Postwar Statecraft in Guatemala." Cultural Anthropology 28, no.. 1: 144–60.

Weaver Shipley, Jesse. 2013. "Transnational Circulation and Digital Fatigue in Ghana's Azonto Dance Craze." American Ethnologist 40, no.2: 362–81.