Thanks for coming to our second Screening Room series. We

hope you were able to enjoy the film! Savage Memory has been taken down,

but this page will be up with the trailer, filmmaker interview and

other teaching resources.

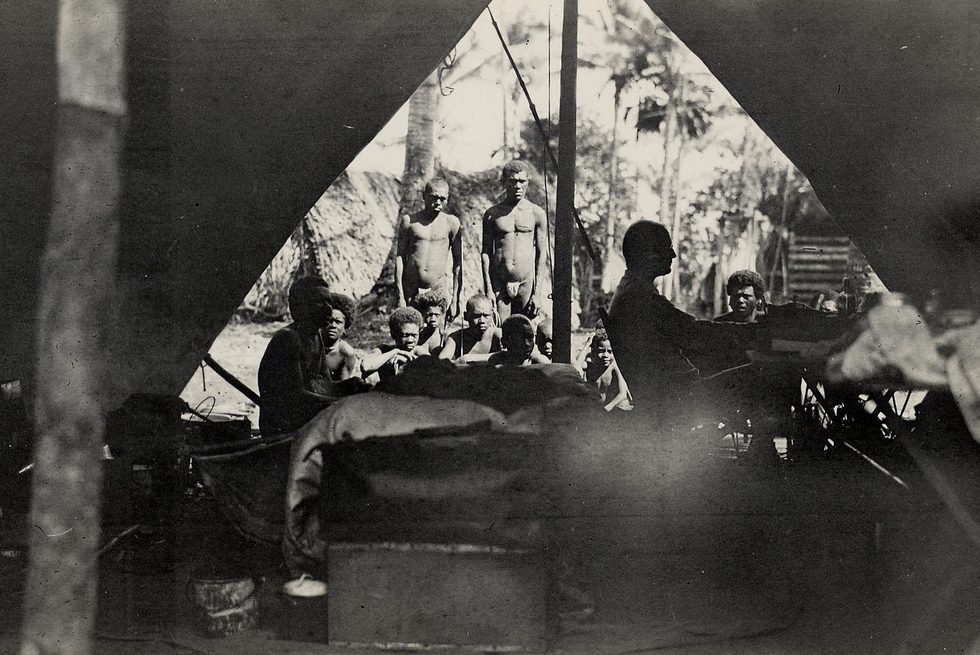

We are excited to present Savage Memory, a film by Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson. For the next two weeks we will screen this feature documentary that explores the history and legacy of Bronislaw Malinkowski, one of the founding fathers of modern anthropology. The filmmaker, Malinowski's great grandson, returns to confront the complex legacy left behind by his great grandfather within anthropology, the Trobriand Islands, and his own family. The film looks at disciplinary and familial history, memory and legacy, utilizing archival, interview and verité material from the Trobriand islands as locals islanders reflect on their relationship with Malinowski and the impact of westernization on their changing customs. A film about ghosts and hauntings, it asks the viewers to question how narratives around ancestry are created, what becomes part of a legacy, and how memories and history are preserved in families, disciplines, and even cultures.

Accompanying the film is an interview with filmmakers Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson, as well as a study guide with additional resources and classroom discussion question.

Synopsis

Savage Memory uses the controversies surrounding the legacy of the founding father of British Social Anthropology to explore powerful questions surrounding history and the ways in which it is created; memory and it's fluidity; and the imprints of the spirits of the dead. Told through the lens of Malinowski's great grandson, the film weaves familial and historical perspectives with rich vertié moments in the site of Malinowski's field work- the Trobriand Islands, an archipelago off the coast of Papua New Guinea.

Biography

Zachary Stuart, Director, trained as a documentary filmmaker at Harvard’s program in Visual and Environmental Studies. His first film This is Just This, uses experimental sound and 16mm film to explore a first-person experience of North India. He produced and directed a documentary short on an ex-prisoner storytelling project “Public Voices.” He has worked on a number of interdisciplinary video and film projects including editing for dancer Hana van der Kolk’s memorial dance piece For Them, and camera work for the film Occupation and Faith Soloway’s Rock Operas “Jesus Has Two Mommies” and “Miss Folk America.” He has traveled to Israel to document an ecumenical Palestinian Pilgrimage which included interviews with Yasser Arafat. Zachary Works as an arts educator and performer for the interactive theater program Urban improv and teaches theater, dance and fine arts for the Freelance Players. He heads the theater department at the Creative Arts at Park summer program

Kelly Thomson, Director, is currently co-producing two PBS documentaries - Denial: An American Dilemma, which uses Gunnar Myrdal's landmark 1940s study of Jim Crow America to investigate contemporary race relations in America and The Raising of America (www.raisingofamerica.org) which looks at the crucial importance of early child development for the future of individuals and our nation. She was Co-Producer/Editor for Gaining Ground: Building Community on Dudley Street, a follow up to the award-winning Holding Ground; Associate Producer for the four-part series, Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick (winner of the DuPont/Columbia Award and the National Science Academy’s Broadcast Award); and Associate Producer for the one-hour documentary, Herskovits at the Heart of Blackness (winner Best Documentary, Hollywood Black Film Festival). She recently served as Artist-in-Residence at the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative where she worked with high school aged youth to create short films. Previously, Kelly has worked on a number of independent films over the past ten years including Wild Art, Hotels 4, All Falls Down, Milk, A Vote for Choice, and Funeral of the Last Gypsy King. She received her BA from New York University in Religious Studies.

Interview with Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson

Patricia Alvarez: What motivated you to explore through film your own family? What were the challenges and overall process of engaging in making biographical essay film, a film about your own kinship?

Zachary Stuart: I was motivated to explore this aspect of my kinship because in looking at my family and their relationship to Bronislaw Malinowski, I was confounded as to why he had been buried so negatively in the recesses of our family history. Of course, now and then I had heard my grandmother speak with pride about his contributions but he really was a bit of a mystery, and there was a tone of resentment that never left his daughters. But what seemed the most interesting about Malinowski’s role in our family is that he was an expert on kinship across cultures, delivered lectures around family structure, marriage and lineage yet his own descendants had no connection to his legacy or his contributions to anthropology. It was this dichotomy that motivated me coupled with the fact that the fundamental issues Malinowski addressed in his work, cultural relativism, cross-cultural understanding and humanism are the things that are closest to my heart.

Growing up in a multi-cultural, urban society (Boston MA, USA) I have always had to navigate a number of cultural worlds. I was always very aware of different cultures coming into contact with each other and this fascinated me, the problems and joys that arise from misunderstandings and positive communication across cultural lines. This is a big part of what Malinowski studied. So in approaching this project I was thinking about the role of kinship in our lives but also the role that anthropology has played in helping humans understand each other.

Patricia Alvarez: The narration feels to constantly sway from intimate moments to creating an almost objective distance between you and Malinowki’s legacy. How was the process of negotiating your own positionality in the film and throughout the process of production?

Zachary Stuart: Crafting the narrative was potentially the hardest part of creating this film. The oscillation between distance and intimacy reflects exactly my relationship with the material. At times, I can only see my great-grandfather as an historical figure, from a distance. But my intention was to try to understand him more intimately and to push myself to look more deeply into his personal influence in my family. But it was often his intellectual work that stimulated me the most. And I struggled between my appreciation for his contributions and my criticisms of him as a man and a scientist.

Patricia Alvarez: Within documentary film Savage Memory seems to speak to the essay film tradition. Why did you decide on this formal approach? What formal aspects of this genre were productive and what themes did it allow you to explore visually and narratively?

Zachary Stuart: Kelly and I are not necessarily fans of the traditional personal documentary, following the narrative structure of a journey that begins with a question and gets an answer. These films are often very focused on the narrator’s personal journey and process. We were more interested in the looking at themes of ancestry, ghosts, spirits of the dead from many angles. We chose our format to work against some of the expectations one might have with a film like this. As a result, it is a layered document that introduces ideas then builds on them in different ways.

Malinowski is most known for his extensive writing, so text was very important for us. He also had a large body of field photographs and personal letters as well as family images. These were the elements that we had to contend with in piecing together his historical and personal legacy. And the themes we were exploring were both very intimate and at other times very heady or conceptual. We decided to piece together text, photographs, animation and impressions with my own voiceover text to let ideas speak to each other around the theme of legacy, hoping to highlight the contradictory factors of this one man and his reverberations down generations.

Patricia Alvarez: I’m interested in how Malinowski’s text was used throughout the film, in a way it felt as his still present-lingering ghostly voice. Can you comment on the use of text in the film?

Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson: After watching a few films about Malinowski that delivered his text, particularly his diary excerpts, in voiceover or by actors, we decided that we wanted to present it as text alone because this is the only way it is available to us now. There are no sound recordings of Malinowski speaking or moving images. What he left behind is his writings. And those writings can be read in different ways by different viewers. We wanted our audience to have that authentic experience of reading his text and taking from it what they might. Of course we made some very clear decisions about what text to include etc… but we wanted people to access it in that way. The stylization and movement of the text was indeed an attempt to make text come alive in a way it might not have otherwise if static.

Patricia Alvarez: Going back to your presence in the film as a narrator. You state that your twin brother is the most similar family member to Malinowski. The film does question the ways in which our personal lives are intertwined in our own professional work. Our personal projects, even Malinowski’s research, is also personal and about ourselves. In what ways is the film also about both of the directors and your own relationship with Malinowski, anthropology and historical legacy?

Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson: We as directors have always been interested in how ideas turn into beliefs, and how beliefs affect our realities. We are both interested in understanding how how belief systems (such as psychology, karma, ghosts and reincarnation) overlap. We were also both fascinated with the idea that memory plays such an important role in forming our understanding of the people before us, even though memory is so fluid.

We are both explorers, we’ve both always engaged with other cultures and religions and questioned the varied beliefs and ideas within our own culture. I think in our fast paced global society, many of us are yearning to feel connected to our cultural heritage, to understand what our ancestors did and how they are affecting us now. Different traditions sometimes offer explanations that are easier to make sense of than others. And we hope that this is part of how people view the film.

It’s worth mention also that as filmmakers, we are not unaware of our role in creating history – so to speak. Every step of the way in the process of crafting the film we were forced to make choices about what to include and what not to include, what questions to ask and of course, what lens we ourselves were using. All of these ideas resonated with the issues that Malinowski’s life and work bring to the table.

Patricia Alvarez: Did you ever find an answer to the question what is a legacy? In the end what do you consider was Malinowski’s legacy?

Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson: We hope that the film shows the many contradictory sides of Malinowski’s legacy as a man and an historical figure, like a rock that is dropped in the water, ripples spread in many different directions, some bigger than others, some subtle. You can see the way in which his ideas permeated aspects of human understanding, the way his choices influenced the way my family felt and behaved, the role his diary played in anthropologists reckoning with their complicated and privileged position. His legacy was composite and complex and each ripple seemingly contradictory with the next. I think for us there wasn’t a single answer to this question and hopefully that is what is reflected in the film.

Patricia Alvarez: How did you decide on travelling back to the Trobriand Islands? How was it retracing his footsteps, seeing the social change and engaging with Trobriander’s point of view and their ‘memory’ of Malinowski?

Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson:Malinowski’s work relied so deeply on his Trobriand data and also on the idea of “participant observation” which was really his main contribution to the field. We wanted to have some experience of what it was like to physically be on these islands but also to hear voices of the descendants of the people he studied and to get their perspective on his work. And Malinowski made a number of predictions about the future of this society and we wanted to see what it looked like today.

We were very well received, but often with so much positivity about Malinowski that we questioned whether people were being overly kind.We expected criticisms of Malinowski’s work, but there were little to be found. What was most surprising was how great Malinowski's work had shaped their vision and understanding of the past.

Patricia Alvarez: Do you have any thoughts on the tension between how Trobriand Islander’s see the work of anthropologists as important, yet they also question or are conscious of the limits of the information anthropologists obtain? I’m thinking about the comment on the work of Annette Weiner.

Zachary Stuart and Kelly Thomson: This is such a complicated issue. With the history of colonialism, cultural exploitation and religious conversion all of this becomes very muddy and unclear. You can see that Bunemiga who discusses the limits of Annette Weiner’s knowledge also burned his spell books when he converted to Christianity. So the limited amount of material Weiner did collect from him, stands to document some of what he burned.

Many of the next generation of Trobrianders are looking to Malinowski’s work to connect to their ancestors and understand their cultural heritage. This is something that many of us are feeling disconnected from as we step into a global society -- to be connected to our diverse lineages and heritage in societies where modernization has obscured these things.

Patricia Alvarez: Finally, the diary. In the film you state the Trobriand Islanders haven’t read the diary. I was curious to know if the Trobriand anthropologists have read it and what were their opinions about it. Secondly, in your own narration you seem ambivalent about the diary. You state that anthropologists understand the diary in its context yet, which is important to do, but you feel they let him off the hook. What are your own thoughts about the diary, how does this speak to the difference between a historical figure and a human figure?

Zachary Stuart: Linus digim’Rina had read the diary but had little to say about it. Most anthropologists who read it don’t give it much weight because it was not intended for publication and many of the expressions of frustration and alienation are typical feelings in the field. However, certainly the racial aspects are quite shocking and can’t be ignored completely.

The diary portion of the film was very much a struggle for me because the statements are very upsetting to anyone who understands global, institutional racism and prejudice. I walk a line in the film between anger and understanding and perhaps this was a mistake. In thinking more about this issue since making the film and also hearing mainstream audience reactions, I actually wish I had treated it differently.

Racism is a plague on the psyche of all mankind. Anyone who has lived in a multicultural society will come to understand this. We are born into it and it invades our minds through our family’s beliefs and prejudices, through our media outlets, through cultural misunderstandings and hate. Becoming less racist is a process that can only come through understanding history, exploring other cultures, questioning the vast power of the media and our own personal experiences. It’s my belief that Malinowski understood this more than many of the scholars of his time. He was a humanist and what he chose to write and publish years after writing the damning diary was a body of work that looked at our common humanity. That is how we ended the film and that is what I personally see as Malinowski’s intended legacy.

Study Guide

This film serves as a great teaching tool to explore and foster discussions on the history of anthropology, memory, kinship and the kind of labor done by anthropologists. In the way this documentary weaves various narratives it explores the history of the development of the discipline, what led Malinowski to carry out extended fieldwork, and the socio-historical context of the discipline at the time and disciplinary legacy. Moreover, the film also creates a space for thinking about Malinowski not only as a historical figure studying kinship, but also embedded in his own kin relationships. It serves as a way of thinking about the different kinship relations that we come to be part of. Finally, the footage from the Trobriand Islands serves as a powerful statement and point of reflection on the consequences and ways in which the work of anthropologists becomes part of the reality of the groups they work with.

Discussion Questions

-Malinowski is often described as the father of fieldwork. What was anthropology like during Malinowski’s time and how did he come to carry out extended fieldwork? What historical situations allowed him to engage in this form of research?

-How did the fieldwork done by Malinowski transform and help shape the discipline and work done by anthropologists?

-How is Malinowski remembered within his own family? In which ways has his memory been passed down through generations?

-In what ways is it different or similar to be the father of a family from the father of a discipline? Compare and contrast the ways he is remembered in each kin relationship.

-What traits from Malinowski did his family members see as being inherited? How do we understand inheritance within Western kinship relations?

-How is Malinowski’s his work meaningful for the Trobriand Islanders and how might this be different from the ways anthropologists find his work meaningful?

-How do we conceive of ghosts, how does Malinowski explain ghosts in Trobriand culture, and how do contemporary Trobriand Islanders define ghosts?

-What is a legacy?

Readings

Kinship Cureated Collection, Cultural Anthropology

Other Related Multimedia

On Malinowski

On Kinship

References

Fisher, Daniel. 2009. Mediating Kinship: Country, Family and Radio in Northern Australia. Cultural Anthropology 24(2):280-312

Grimshaw, Anna. 2001. The Innocent Eye: Flaherty, Malinowski and the Romantic Quest. In A. Grimshaw (Ed.), The Ethnographer's Eye: Ways of Seeing in Anthropology (pp. 44-56). Cambridge University Press.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1992. Baloma, Spirits of the Dead in Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays.

Schneider, David A. 1980. American Kinship: A Cultural Account.

Stasch, Rupert. 2009. Society of Others: Kinship and Mourning in a West Papuan Place.

Young, Michael A. 1998. Malinowski's Kiriwina: Fieldwork Photography 1915-1918.