Serial Sires: On the Reproduction of Cows in an Era of Genomics

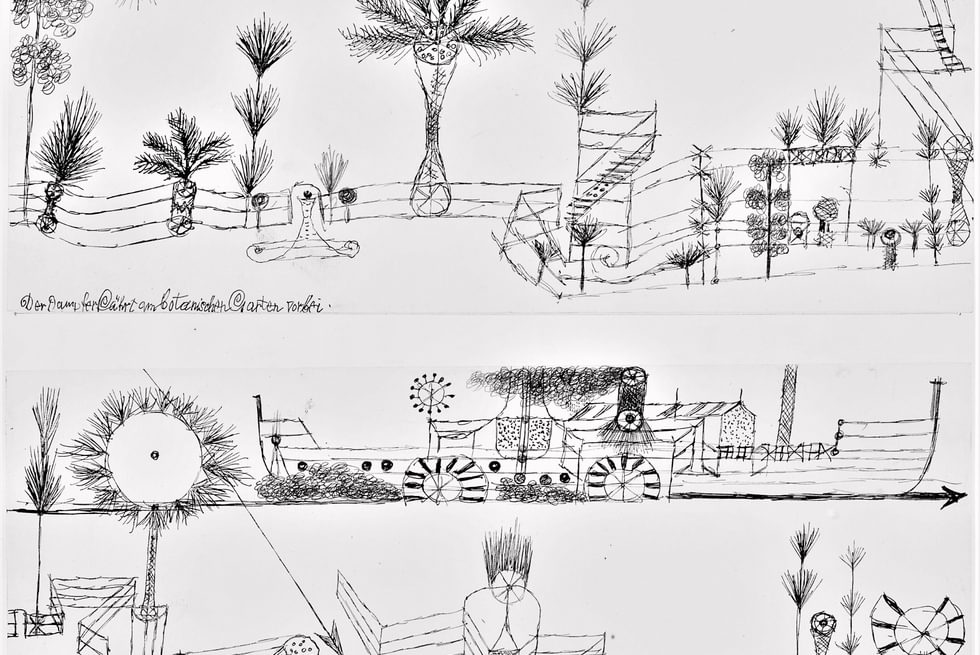

From the Series: Plantationocene

From the Series: Plantationocene

Ciney, Belgium, is the center for reproduction for the bovine breed “Belgian Blue” (in French, blanc bleu belge, abbreviated as BBB). The building has been built recently in a transparency effort towards consumers. This endeavor includes a public exhibit around the selection and reproduction of bovine bodies that aims at standing in between tradition and progress. This exhibit was commissioned by the Walloon Association of Livestock Farmers (AWÉ), a former farmers cooperative now turned into a public agency funded by the ministry.[1] It celebrates the abilities of rurality to modernize with the progress of technological innovation.

The most striking part of the public-facing space is the core pictures exhibit in the main hall. There, some montages show layers of white and black cow skin fragments that increasingly turn into a QR code-like pattern. The in-vivo counterpart of that exhibit happens below, where one can see two main rooms through large window panes. In the left room, semen is sampled from elite bull sires under the careful supervision, and with the active guidance of, bouviers (literally, a person charged with conducting buffalos). This semen will be sold to inseminate thousands of females worldwide. But, for now, it is brought immediately to the technical laboratory in the room on the right, where it is tested and analyzed in a matter of minutes. The semen’s values, quality, and vivacity are then displayed on a large screen in the room on the left, for everyone to witness their performances. If it is good enough, the semen sample is then validated and conditioned in colored plastic straws of vivid orange, red, or lime green, and then frozen in liquid nitrogen for export trade markets. If it is not, it is discarded.

My attention was captured by a large frame that dominates the welcome desk at the entrance. This artwork represents the head of a sire reproduced nine times in a particularly vivid and colorful background. The plaque mentions the title of the piece, “United Colors of BBB.” It pays a tribute to Andy Warhol’s Marilyns or canned beans, in a celebration of the “unity in diversity” that brings together the different institutional components of AWÉ. The bull himself, the plaque goes on, sublimates this cohesion: “the artwork reveals all of his power and, through his gaze, a discrete softness.” In this picture, “nature” (the bull) stands as one, while “culture” (humans and their institutions) stand as many. It involves what I could call a mononature.

This bull has a face and agency, yet it has no name. It remains anonymous while being pictured for its singularity. Its sameness runs through the nine replicas while each one has its own background color, signaling its own tone, like a voice in a chorus. Just like monoculture, the replication of sameness requires the production of a conductive milieu (Besky 2020).

Further down the building are the boxes where about thirty Belgian blue cattle elite sires are awaiting semen sampling. Each one has a name. They are pictured as superstars in catalogues, with their performance traits gathered from various indexes. Their semen will be mostly sold abroad and will be used to inseminate thousands of cows, sometimes with Belgian blue cattle cows for meat production or, most likely, in cross-breeding for the dairy industry, where these calves will also end up producing meat. And then, on rare occasions, the semen of elite sires will be used to reproduce other elite sires. So, on the one hand there are masses of calves destined to the slaughterhouse and, on the other, a handful of singular bulls who gained the right to be named according to their performances and individual credentials.

This somehow echoes the whole infrastructure of selection and reproduction using genomics. Though mostly used in the dairy sector (where the phenotype matters less than in the meat industry), this infrastructure rests on a sequencing of the Bos taurus genome. This reference genome of the species is used to test populations of cattle. It forms the backdrop against which the qualities of individuals can be contrasted and heralded for producing value. It takes a uniformed landscape to be able to detect a specific color, or shape, that distinguishes itself from the rest. Data analysts and bioinformaticians know very well that what matters most—and what is most difficult to achieve—is noise reduction. Compare, if you will, this noise to the anonymous masses of calves destined to slaughterhouse, and the significant or relevant gene to the superstar reproducer that gets a name and a picture.

In contemporary livestock industry, there is a logics of the plantation: mass production of sameness, homogeneity, and scalability. These processes are of course not seamless (Blanchette 2020). They require the actual work of reproduction which is always a work of the difference. To start with, genetic selection would not be possible in the first place if it wasn’t for the variations that occur all the way through reproductive labor. As Hennion and Latour (2003) put it in their discussion of Benjamin’s essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, reproduction always implies re-creation, and techniques are all but mechanistic.

It is no wonder that a Warhol-inspired artwork dominates this scene. In a way, this piece is telling us that there is nothing to be ashamed of in making surplus value out of the serial reproduction of living beings commodified through their masses of muscles. This series of sires are cared for and maintained for reproductive work. However, just like in Warhol’s art, the series never entails replicas but reproductions. That is a reproduction of sameness which is never identical but slightly differs, from one individual to another. Most of these potential divergences will never be cultivated and will simply end up at the slaughterhouse. My intent in capturing this scene is to show how a difference that matters happens as an event in such an infrastructure. Just as in Warhol’s work, series gain value in an economy of singularities that does not prevent, but on the contrary allows for a political economy of mass production. Elite sires are recognized and, unlike the anonymous masses of calves destined to the slaughterhouse, they have a face and a name.

Funded by the European Union (ERC, The BoS, GA959477). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

[1] To this day, AWÉ is still ran by certain farmers, the ones who have the time and means.

Besky, Sarah. 2020. “Monoculture.” In Anthropocene Unseen: A Lexicon, edited by Anand Pandian and Cymene Howe. Goleta, Calif.: Punctum Books.

Blanchette, Alex. 2020. Porkopolis: American Animality, Standardized Life, and the Factory Farm. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Hennion, Antoine, and Bruno Latour. 2003. “Authenticity: How to Make Mistakes on So Many Things at Once—And Become Famous for It.” In Mapping Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Digital Age, edited by Hans Ulrich Gunrbrecht and Michael Marrinan. Redwood City, Calif.: Stanford University Press.