Socialist Greens: On Vernacular Environmentalisms

From the Series: Green Capitalism and Its Others

From the Series: Green Capitalism and Its Others

Popular discourses about environmental mobilizations in socialist Eastern Europe frequently frame these movements as nothing less than revolutionary. Reacting to the presumably exceptionally environmentally destructive nature of state socialism, these movements are said to exemplify the awakening of “civil society” which eventually brought down entire regimes in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Such narratives of environmentalism-as-opposition obscure the role that vernacular and state-supported environmentalisms played in articulating “green” visions of nature, society, personhood, and politics, both within and without the auspices of the socialist state. Socialist citizens’ associations (udruženja građana), such as the ubiquitous Planinaraska Društva (Mountaineering Societies) and the unique Unski Smaragdi (the Una River Emeralds) in socialist Yugoslavia provide insights, however partial, into the politics, philosophies, strategies, and pedagogies of these “socialist greens.”

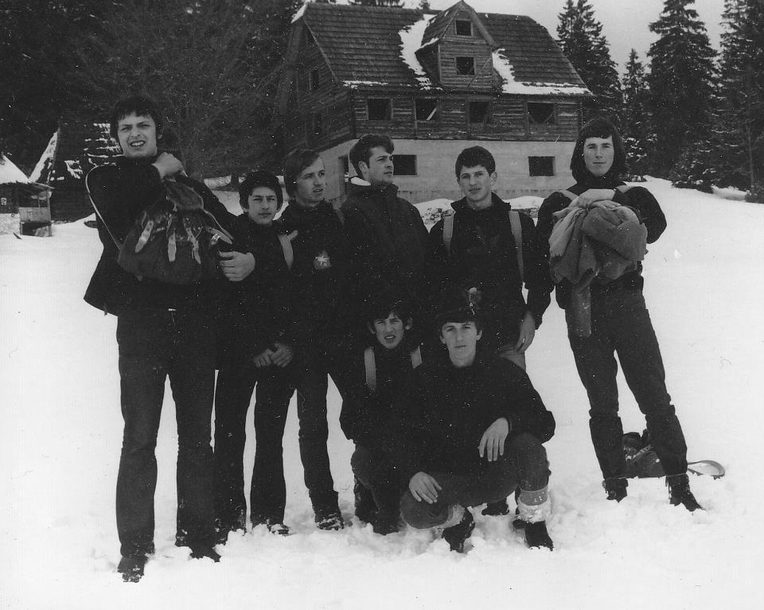

We first turn to one of the region’s most popular and beloved pastimes: hiking and mountaineering. In the largely mountainous Bosnia-Herzegovina, the network of Planinarski domovi (literally, “houses of mountaineers”) are some of the earliest examples of civic associations. As leisurely activities, mountaineering and hiking first became popularized in Bosnia during the 1878–1919 Austro-Hungarian rule, when many of the existing societies were first established. However, the socialist period was a golden age of these kinds of associations, in part due to the affinity between mountaineer and socialist ethos. Much like in Weimar Germany, where proletarian hiking clubs formed part and parcel of the socialist government’s effort to improve human condition and combat alienation generated by capitalist industrialization and urban life, in socialist Yugoslavia, mountaineering societies were lauded as sites of human development, multiethnic and multigenerational forms of sociality, state-sanctioned forms of patriotism, and, most importantly, environmental ethos and consciousness. Such clubs were instrumental to the survival as well as recruitment of a new generation of Yugoslav communists, who, after the party became illegal in 1920, withdrew into nature in order to clandestinely read revolutionary texts.1

Under the auspices of a new state that sought to build new socialist men and women through various forms of associationism, mountaineering societies sought to promote a type of vernacular environmentalism that was tied to a specific conception of a good and healthy life, lived in communion with nature. Planinari sought to care for the natural world in their zones of operation, promote reforestation and conscientious use of trails and natural resources, encourage knowledge about natural environment, and popularize practices such as harvesting herbs and picking forest mushrooms. While they were also famous for their penchant for good times (accompanied by food and alcohol), in unassuming and often indirect ways, their clubs sought to merge ideals of active citizenship with particular practices of sociality that emphasized friendship, a healthy life, and respect of nature.

Indeed, in contemporary Bosnia, burdened by continued nationalist strife and political paralysis, planinari are nowadays often described not as strange loners, but as the most exemplary and the most “normal” of people. This reputation issues out of their commitment to nature as a site that offers escape from politics, a place of caring and being cared for, where more productive forms of self and sociality can be forged. Paradoxically, this is also the reason mountaineering has now become central to the work of imagining a more desirable future—in particular, through new schemes promoting eco-tourism as a panacea for Bosnia’s ailing and postindustrial economy. Initiatives seeking to build these “green futures” do not always acknowledge that they are precisely made thinkable and actionable through the infrastructures and ethical materials left behind by the old system.

Socialist environmentalisms were also profoundly formative, as the case of the Una River Emeralds association shows. The Una River frames the Bosnian northwestern border with Croatia, and is famous for its beauty, fast currents, emerald color, water quality, tourist potential, and for keeping Bihać’s population sane and safe during the 1990s war. The intimate relationship between Bihać’s inhabitants and the Una River was solidified on May 17, 1985—the river’s official “birthday”—when an Ecological Association, Unski Smaragdi (The Una River Emeralds) was established by Boško Marjanović, a lawyer, journalist, children's ecologist, publicist, writer, and essayist. At its peak, the association included 113,200 members, “friends of the river,” from ninety-seven countries.

The association’s mission was to increase the ecological consciousness of Bihać’s children and to produce ecologically conscious socialist youth. These “river ambassadors” were to advance the culture of Una’s preservation and protection. With its widely popular pseudo-philosophical slogans, such as “The Una River should not be protected from people, but we should teach people to guard Una” and “Clear Mind—Clear Una,” the association was able to capture people’s unique relationship to the river and transform it into a prolific pedagogy that fostered a distinctive ecological milieu and political repository. Furthermore, by using the seemingly apolitical discourse of “childhood innocence,” the organization was able to engage in “the political”: on behalf of the river and children, it fiercely, boldly, and globally lobbied with scientists, artists, politicians, and lawmakers.

The Emeralds’ distinctive socialist green approach incorporated two frequently contrasted perspectives. The first is sometimes referred to as the “western epistemological tradition” which separates “humans” and “nature” and assigns politics to humans while delegating non-human subjects to the symbolic realm and scientific examination.2 This approach was palpable in the Emeralds’ restless scientific classifications and official valorizations of the river’s material worlds. However, a different viewpoint was also present in the association’s speeches and literary publications. Evoking primordial sensibilities and deep (human and non-human) histories, it incorporated multiple and divergent worlds, and it fostered a unique form of connectivity between humans and the river. As a result, the distinction between the river and humans was experienced and described as porous. A unique form of affective politics emerged from this relation, producing a “City in Love with the River” where love is literal rather than metaphoric, and where persons and the “riverine things” are experienced as multiple and mutually constituted. The Emeralds’ approach was therefore both instrumental, scientific, and systemic, as well as philosophical, artistic, poetic, and ontologically plural.

These two cases reveal that socialist environmentalisms were state sponsored yet simultaneously vernacular and largely “deterritorialized” (Yurchak 2006) from the official realm of communist politics. Furthermore, these green visions and strategies, based on local environmental sensibilities, suggest that Yugoslav socialist regime was always an ecological regime and that just like capitalism, it too sought to organize nature and the place of human in it (Moore 2015). These socialist greens practices unfolded in ways that simultaneously reflect, confront, and complicate the contours of the Iron Curtain politics as well as the contemporary understandings of the Green Screens.

1. We are thankful to Sabrina Perić for this insight.

2. We thank Jay Prakash Sharma for helping us think about this issue in relation to the Una River.

Moore, Jason W. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. London: Verso.

Yurchak, Alexei. 2006. Everything was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.