This post builds on the research article “Sounds of Democracy: Performance, Protest, and Political Subjectivity,” which was published in the February 2018 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Sean Furmage and Andrés García Molina: Could you talk a little about how you decided to include sounds in your article?

Laura Kunreuther: I wanted to think about what we learn ethnographically when we are thinking through sound and not just through words. And I think that was inspired by this digital moment we’re in, but also by listening to some of the recordings done by anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, and sound studies scholars that are both inspired by and critique the concept of soundscape. I realized that a lot of what I was talking about in this article, I couldn’t adequately describe in words. And that performers like Ashmina and activists in Occupy Baluwatar were using sound in a very deliberate way that might enhance or inform the way that I wrote the article.

Plus, publishing infrastructures are changing so that sound can now be more than just illustrative of the written content. I have often thought about what it would be like in, say, Stefan Helmreich’s (2016) rich article about gravitational-wave detectors to hear the deep whirring of those sounds that he embedded in the piece immediately as the article loads, instead of having to click “play” in the media player. I don’t think that capability was available when Helmreich wrote his article, nor was it necessarily what he wanted to do.

SF and AGM: We would love to hear more about how you are thinking about this relationship between writing and sound in your work.

LK: It’s been a really rich question for me, in part because it asks us to read differently. We typically think about reading as a silent activity. And, as Ana María Ochoa (2015) has pointed out so well, this kind of silence has its own politics. I think, in this, new digital moment, there is an opportunity for us to think about reading differently—because people are reading differently—and to think about the different registers of scholarly engagement that might be enabled by the inclusion of sound.

It’s also important to remind ourselves that reading has not always been silent. And it isn’t, across the world, silent. Francis Cody writes about people reading the newspapers out loud in Tamil in southern India. Even in the poetry room at the Harvard University libraries, as my colleague Olga Touloumi has discussed, reading was not always silent: the poetry room was a place where you would listen to poetry read out loud on a portable Victrola. And, of course, poetry is a written genre that is all about sound. But, for us as scholars, it’s an interesting challenge to begin thinking about how people around us are recording sound and what we might do with that, ethnographically.

This is how I would distinguish what I’m doing in this article from some of the earlier work in the anthropology of sound. It has been really rich and I have taken a lot of inspiration from it. Part of what people like Steven Feld and Donald Brenneis (2004) have done was try to raise the level of technological artistry in places that were not getting much attention, using the most high-fidelity audio equipment in order to have really good sound quality. What I’m doing in this article is a little different, because I’m using—well, some of the stuff is actually not very good-quality, in the sense that it’s recorded with a cell phone. And not all of it is recorded by me. So it involved a very different ethnographic process, because I was working with people who had recorded this stuff for their own personal archives. They generously gave me the sound and worked with me. The engagement I had with informants in the process of writing this article was much more involved than in any other article I have written. Because people don’t or can’t necessarily read in the same way that they can listen to sounds with which they are themselves working.

SF and AGM: Could you talk more about how you put together the recorded sounds, for example in the Kathmandu āwāj piece at the beginning of the article?

LK: That piece was inspired by trying to think about what I heard and what others around me heard over the course of the day as a basic, everyday soundscape. I wanted to think about how those everyday sounds were being used by artists and activists in their performances. So I wanted to give people a sense of a sort of fictive day. Those recordings were not all made in the same day. And they were made deliberately, in consultation with people who I asked: “What are the kind of iconic sounds of Kathmandu?” They were also made in dialogue with the kinds of sounds that the activists themselves were using in Occupy Baluwatar, which are very typical sounds—the bells they used come from their own puja (worship), and the honking and whistles on the street as well.

So one of the interesting things is that I had recorded some of this material during one visit and then I went back, thinking “okay, I’m really going to put together this piece.” But during this second visit—I think I mention this in a footnote—a law had been passed such that no honking was allowed on the streets anymore. And so the soundscape was really different! Amazingly, within four days of the law being passed, taxi drivers and everyone else just stopped honking. I got off the plane thinking: “Wow, this is almost like a different city.” There are a lot of laws like this that don’t work. But this one worked. There must have been enough people who decided they just didn’t want to honk anymore. It is quite striking, because it was the habitual way of driving. So the kind of performance in which the activists were engaged could not have happened in the same way after the passage of this law, because drivers wouldn’t have been able to honk.

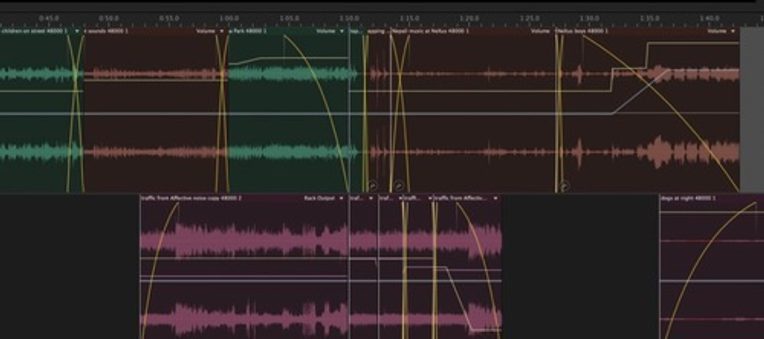

SF and AGM: When we proposed this interview, you told us that you wanted to include a screenshot of the editing process. What do you hope readers will take away from this image?

LK: What’s nice about the visualization is that you can immediately see that this piece is edited. There are two tracks in the section shown here, and I did a lot of work with my colleague Bob Bielecki, a professional sound designer and engineer, to make sure that listeners could hear the sounds of the guitar while hearing the barking of dogs that also marks the evening hours. So it should be thought about as a kind of crafted piece, just as one would craft a written piece.

I think one of the problems that happens with sound is that people initially think about it as a sort of direct access to a place, an assumption that scholars in sound studies are trying to undo. You know, it’s not a transparent medium. And, again, some of the pieces that were given to me were other people’s recordings, which they themselves edited. I think it’s important to point that out. These are strategic uses of sound, both in my own rendition and in those of performers like Ashmina and other activists, both in their recording of it and in posting it online as many of them did. So I think readers ought to see and to understand that, when you have a recording of sound, you’re not just immediately taken right to that place. Recording is itself a kind of mediated experience.

I think one of the problems that happens with sound is that people initially think about it as a sort of direct access to a place, an assumption that scholars in sound studies are trying to undo. You know, it’s not a transparent medium.

SF and AGM: In one of our early conversations, you mentioned the idea of differences in hearing. Could you say more about how you’re thinking through this concept?

LK: This part is quite personal. A conversation with my mother-in-law, who has profound hearing loss, inspired me to start thinking along these lines when I was talking with her about this project. I was planning on visually presenting the edited version of the “Kathmandu āwāj” piece at a conference, so people could watch as the sound was playing and see how edited the piece actually is, how many different things are going on. So I showed her the edited sound piece and she found it incredibly frustrating. She has only about 7 percent of her hearing and she basically told me: “I’m watching what I can’t hear, and I don’t really want to do that.” I realized that the article depends—for it to work, for the writing and sound to work together—it depends on a certain ability to hear. Having read some of Mara Mills’s (2015) work and others who talk about differences in hearing—Jonathan Sterne (2016) is also writing about hearing differences in his new work—I just wanted to put it out there that not everybody will experience this article in the same way.

I don’t know if I have an answer for how I would address these differences in hearing, except to acknowledge that they exist—even, I believe, across the spectrum of the so-called normal hearing population. I did make a choice to include only sound and not audiovisual material; one of the sound clips was connected to a YouTube video and the editors asked me whether I wanted to include the video or not. I decided not to, because the piece is really about sound. And I felt like the video was going to take you somewhere else. But had I included the video, it would have been a different experience for somebody who was not hearing the rest of the sounds played throughout the article. I bring this up because I want to acknowledge certain limits. A blind person would be able to hear this article being read to them, and that would be different than someone who reads silently and then begins to hear the sounds while reading. That’s also part of the point of listening to spaces in the city. Which is one of the ways that a blind friend of mine in Kathmandu says that he gets around. He knows where he is by what he hears.

SF and AGM: Have you thought about a project with your friend or with other folks who might experience the soundscape of Kathmandu differently?

LK: That is a really interesting question. The friend of mine who’s blind is an interpreter. And I think his blindness contributes to his intense ability to hear—I mean, he’s also brilliant—but he has an intense ability to take in an enormous amount of sound and language and to replicate it easily. Well, not easily, but he was one of the more sought-after interpreters in Kathmandu at the time that he was doing this work regularly, and he is not the only interpreter in Kathmandu who is visually impaired. So he is one of the people who are getting me attuned to thinking about interpretation and sound, because that is very much what he does daily. I remember him saying: “When I’m on the back of a motorcycle, riding on the back of a motorcycle with people, walls speak to me. I can hear us getting close to a wall. I know I’m close to a wall because I can hear a shift in the sound.” So you’ve given me an interesting idea. I have been working with this friend in a different context, but it would be interesting to do a sound piece with him.

References

Feld, Steven, and Donald Brenneis. 2004. “Doing Anthropology in Sound.” American Ethnologist 31, no. 4: 461–74.

Helmreich, Stefan. 2016. “Gravity’s Reverb: Listening to Space-Time, or Articulating the Sounds of Gravitational-Wave Detection.” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 4: 464–92.

Mills, Mara. 2015. “Deafness.” In Keywords in Sound, edited by David Novak and Matt Sakakeeny, 45–54. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Ochoa Gautier, Ana María. 2015. “Silence.” In Keywords in Sound, edited by David Novak and Matt Sakakeeny, 183–92. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Sterne, Jonathan. 2016. “Audial Scarification: Notes on the Normalization of Hearing Damage.” Lecture delivered at “Sound in Theory, Sound in Practice” symposium, Bard College, April 7.