Standardizing Animal Mobility and Locations

From the Series: Plantationocene

From the Series: Plantationocene

Around two billion live animals are transported across the world annually. Most have been bred to ensure uniform characteristics best suited to human commerce. Their movements are tracked and regulated in an attempt to reduce the spread of infectious disease. The main motivation is to protect industrialized animal farming from itself. This has created new kinds of locations, defined as zones that are affected by, or free from, certain infectious diseases. These zones crosscut administrative regions, leading to sometimes fatal confusion over where farm animals have come from.

* * *

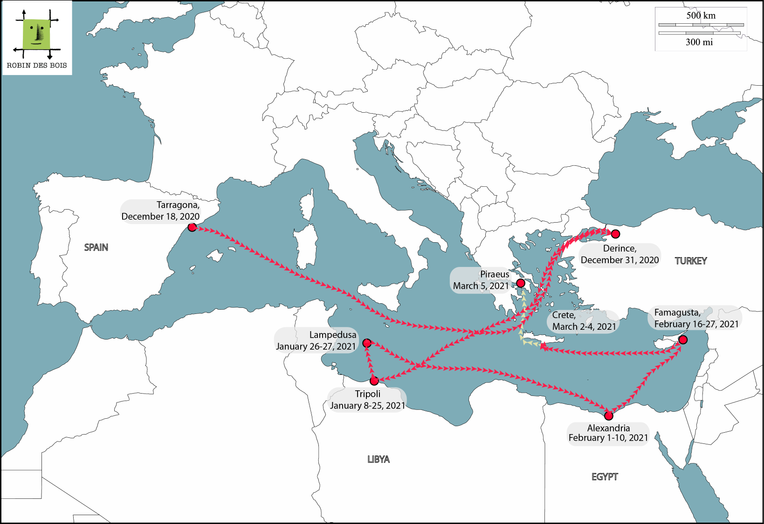

The Elbeik and Karim Allah are two old cargo ships used to carry livestock across the Mediterranean. In late December 2020, both ships had a cargo of live cattle from Spain destined for Turkey. Neither was permitted to offload the cattle in Turkey: the Turkish authorities said the paperwork showed that the animals came from Aragon, a region of Spain that had recently reported an outbreak of bluetongue disease. The captains of both ships protested that the certificates for the cattle showed that they were safe, but to no avail; they were not permitted to offload their cargo.

After this, both ships wandered across the Mediterranean from port to port, looking for other buyers for the cattle. What was originally planned as a ten-day trip stretched into three months. Eventually, both ships were ordered back to Spain, arriving at the port of Cartagena in March 2021. Veterinary inspectors and customs officials declared that the animals were no longer permitted to enter Spanish territory because the ships had visited ports that were not certified for animal exports to the European Union; and they stated that the cattle on board were no longer in fit to be transported anywhere else either. So the Spanish authorities ordered that all the animals, almost 3,000 of them, should be destroyed (Joaquín Ortega Abogados 2021).

At the time, the media reported this story as a tragedy that should never have happened. That was true, in that these kinds of entirely catastrophic results rarely occur. Yet the Eurogroup for Animals notes that many of the regulations often fail to be enforced. Old ships, equipment that does not work properly, inappropriate facilities for the animals while travelling, and inadequate government staff and resources to enforce the law all mean that the regulations are flouted as a matter of course. And the problem is increasing, because global live animal export trade has quadrupled over the last fifty years, with at least five million live animals in transit every day (the majority being chickens, followed by pigs, cattle, and sheep). Both the intensification of farming, which concentrates where the animals are located, and an ever-increasing global demand for meat has meant that farm animal transport is booming (Phillips 2015; Urbanik 2012).

Livestock transport brings together two elements that are relevant to the idea of the Plantationocene: standardization and bureaucracy. Together, these processes fundamentally affected the mobility of farmed animals in a way that systematically reduced their mobility in one sense, while massively extending the distances livestock could be transported in another. The standardization not only involved turning animal farming effectively into factory activity (Lymbery and Oakeshott 2014, 14–24); it also involved redefining the relation between animals, land, and location, and creating a standardized system for moving animals across space. In the past, there was a diversity of ways in which animals were farmed across the world, in addition to a diversity of the kinds of animals involved. In many of these arrangements farm animals such as goats, sheep, and cattle moved around the landscape according to the seasons, and in some cases travelled long distances on foot (Bollig, et al. 2013; Chang 1993; Green and King 1996; Evans-Pritchard 1940). This changed, first during the colonial period, during which European farm animals were introduced to most of the colonial areas, and then later during industrialization, when breeding techniques and mass production techniques narrowed the diversity and standardized the animals being farmed (Chaiklin, et al. 2020; Wilcox and Rutherford 2018; Urbanik 2012; Anderson 2006; Crosby 2004, esp. Chapter 8). The animals were then kept indoors and fed standardized food. Farm animals became ever more static, moving only when they were being transported for trade or slaughter.

At first, international regulations on conditions of animal transport concerned attempts to control the spread of animal-borne diseases such as rinderpest, foot and mouth disease, and swine flu. Issues relating to animal welfare came much later and are still under negotiation, as taking proper care of animals costs money and time, both of which run counter to the main reason for the transport: trade. As livestock trade increased, the risk of spreading disease also increased dramatically. The World Animal Health Organization (the OIE) was founded in 1924 to globally monitor the outbreak of infectious diseases in farm animals and to set up procedures and regulations for limiting their spread. The OIE now sets the World Trade Organization’s standards for live animal transport. The Elbeik and Karim Allah were carrying certificates that used the OIE’s standards. The certificates specify where the animals have come from; the receiving authorities check that information against the OIE’s constantly updated list of outbreaks of disease.

However, in the case of the Elbeik and the Karim Allah, there was a difference between Spanish and Turkish authorities in how the location of the animals was understood. The Spanish authorities certified that all the cattle came from a “zone” (not named in the certificate, but it was Zaragoza) that was certified by the Spanish Veterinary Authority as being free of bluetongue disease. The Turkish authorities instead based their decision on the “region” of Aragon to locate the animals, as that was the only name mentioned in the certificates. The bluetongue disease had indeed occurred within Aragon, but Zaragoza, which is part of the administrative region of Aragon, had been certified as being outside the area affected by bluetongue disease (Joaquín Ortega Abogados 2021, 12–13).

In other words, there were two different locations for the cattle: one defined by OIE standards as what counts as a location infected by bluetongue; the other defined by the Spanish state as an administrative region. The confusion led to the impossibility of landing the animals anywhere, trapping them in a three-month long journey with no destination. The end result was the severe suffering and subsequent death of 2,776 cattle. While industrialization and standardization have the effect of making production of anything scalable, as Anna Tsing has argued (2015), of effectively removing the significance of location—this example shows something else as well: that particular locations, as defined by standardized systems, continue to be hugely important (is there or is there not bluetongue disease there?). Moreover, the coexistence of different ways of scaling and locating things (administrative regions, veterinary zones, etc.) can make the difference between life and death.

Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. 2006. Creatures Of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bollig, Michael, Michael Schnegg, and Hans-Peter Wotza, eds. 2013. Pastoralism in Africa: Past, Present, and Future. New York: Berghahn.

Chaiklin, Martha, Philip Gooding, and Gwyn Campbell, eds. 2020. Animal Trade Histories in the Indian Ocean World. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

Chang, Claudia. 1993. “Pastoral Transhumance in the Southern Balkans as a Social Ideology: Ethnoarchaeological Research in Northern Greece.” American Anthropologist 95, no. 3: 687–703.

Crosby, Albert W. W. 2004. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1940. The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Green, Sarah, and Geoffrey King. 1996. “The Importance of Goats to a Natural Environment: A Case Study from Epirus (Greece) and Southern Albania.” Terra Nova 8, no. 6: 655–658.

Joaquín Ortega Abogados. 2021. Accountability Report: The Karim Allah and Elbeik’s Crises – Animal Welfare during Sea Transport. Report.

Lymbery, Philip, and Isabel Oakeshott. 2014. Farmageddon: The True Cost of Cheap Meat. London: Bloomsbury.

Phillips, C. J. C. 2015. The Animal Trade. Wallingford, U.K.: CABI Digital Library.

Tsing, Anna L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Urbanik, Julie. 2012. Placing Animals: An Introduction to the Geography of Human-Animal Relations. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Wilcox, Sharon, and Stephanie Rutherford, eds. 2018. Historical Animal Geographies. New York: Routledge.