“We need other kinds of stories,” Donna Haraway implores as she faces the camera. “Storying otherwise,” in Haraway’s expression, is an apt characterization of the work of this paradigm-shifting thinker, whose contributions to feminist studies of science and technology resist and even rebel against hegemonic ways of thinking and living. But what form should such stories take? What might they sound or feel like? To watch Fabrizio Terranova’s Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival (2016) is to know that the filmmaker took Haraway’s imperative to heart. Both subtle and explicit filmic techniques mimic, comment on, and evoke the rhythms that sustain Haraway as a thinker, a storyteller, and a human being. In experimenting with different kinds of storytelling—bending the genre of documentary by fusing the intimate everyday with the playfully surreal—Terranova brings one of the most evocative social theorists to life and demonstrates the supple, transformative nature of storytelling itself.

Terranova draws us into Haraway’s world in California: with close frames of shadows interspersed with pockets of light, we feel the heaviness of the redwoods as they give way to glimpses of sky or hang heavy with mist. We are brought into the intimate aurality of the everyday, as the soft sounds of Haraway’s dog Cayenne licking her paw in the early morning hours and close-ups of Cayenne’s abdomen rising and falling with breath evoke a sense of the in-between. At one point Haraway excuses herself to quell some unseen barking. The camera remains on the table as we hear Haraway in the background calling for her partner, Rustin, and then the opening and shutting of doors.

We learn that Haraway’s home is an environment she constructed along with human and nonhuman companions. Photographs and video footage from the 1970s tell the story of the home’s coming into being as a sanctuary for Haraway’s writing and thinking, as well as experiments in what she calls “ways of living for which there were no particular models.” We come to know the world in which Haraway became a writer. In her library, we see the books that influenced Haraway’s worldview, the shoulders on which she stands: female writers of science fiction and anchors of the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. We likewise gain insight into the influence of Haraway’s Catholic upbringing, whose ritual (in Haraway’s words) “made live for an audience what made something vital.”

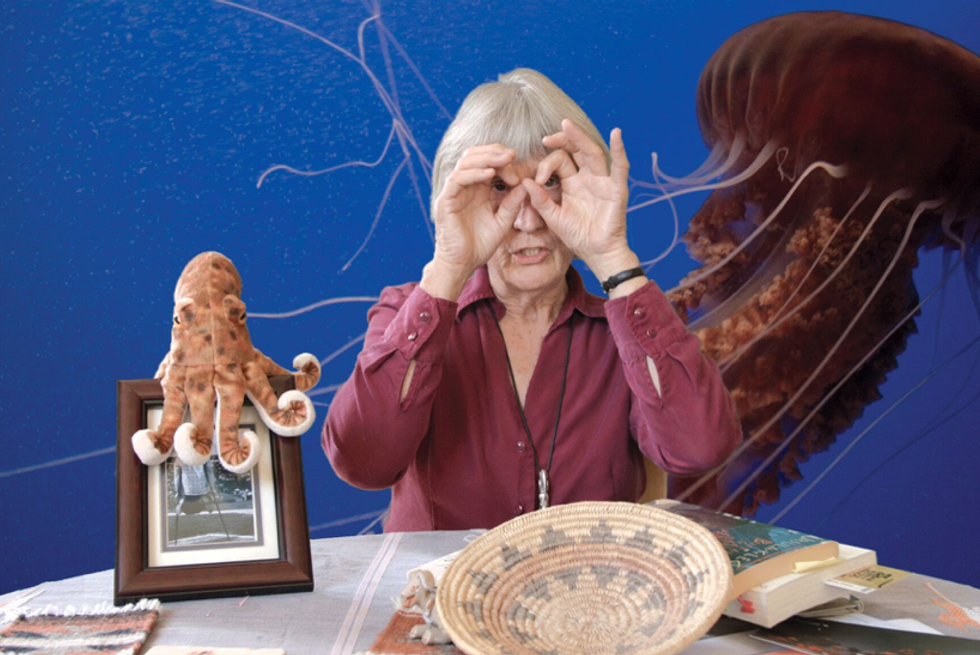

Yet Terranova’s depiction is not a mere biographical portrait. Just as we might begin to mistake it as such, filmic techniques step in to subvert it, returning us to the titular task of storytelling for earthly survival. Even as we are offered glimpses into Haraway’s everyday, we are equally drawn into the playfulness of Haraway’s world: its randomness, its stochasticity. Superimposed images of octopi, cyborg dogs, tentacular tendrils, and even text reminding us that “we are all lichens” flash across these place-settings, pushing cinema verité into the realm of the surreal while staying anchored in a strong sense of situatedness. Close-up shots of Haraway conversing with Terranova, made with a handheld technique that evokes “being there,” are jolted by a giant jellyfish that appears in the corner of the frame, pulsing, its electric tendrils extending behind Haraway’s chair. Haraway continues speaking, unfazed. We get the sense that she is equally complicit in and inured to these “companion species” (Haraway 2003), as if they are housemates going about their own business.

While striking, Terranova’s use of the green screen is rarely explicit. Rather, it grows throughout the film, as one hones an awareness of it. For instance, while Haraway and Terranova are engaged in conversation, we see a figure through the door, seated with its back to us, typing at a computer. What one first assumes is another housemate is soon revealed to be Haraway—the same maroon shirt, the same white hair—typing vigorously away at the keyboard. Yet simultaneously, there she is, addressing the camera. When remarking on the utility of the cat’s cradle as a metaphor for storytelling, she is simultaneously sitting in a lawn chair outside the window of her office, reading. As the film plays with the viewer’s sense of a linear narrative, this iterativity takes on a discursive quality, situating Haraway in the multiplicity of storytelling: reading, writing, speaking, in their simultaneity. By the end of the film, Haraway herself addresses the green screen, playing with it, holding green objects up to the camera to create transparencies as she rejoices: “Holes in being at last!”

These idiosyncrasies capture the cadences of storytelling itself, or at least the kind of storytelling that Haraway advocates. Interruptions happen. Tangents are followed. Threads are woven, tangled, and untangled. As such, it is useful to have a degree of acquaintance with Haraway’s work in order to follow the cat’s cradle that Terranova’s film composes. As a medical anthropologist with an interest in embodiment, sensory ethnography, and experimentation with prosthetic devices, I am attuned to film’s affordances as a medium and its potential to actively engage audiences’ sensoria. Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival does just this. It demands something from the viewer (or experiencer, since the film is just as aural and tactile as it is visual). Precisely in its rebellion against more traditional practices of visual narrative, the film requires those experiencing it to participate, to move with its ebbs and flows. This participation provides another point of entry into Haraway’s work, an almost-embodied praxis of sorts.

“Thinking is a materialist practice with other thinkers,” Haraway remarks at one point. Terranova’s film, from this vantage, is less concerned with representation than with thinking-with Haraway, materializing the very practices she advocates. “Some of the best thinking is done as storytelling,” she later adds, which perhaps explains why ethnographers have been so drawn to Haraway’s theorizing in crafting “ethnography in the way of theory” (Biehl 2013). As such, we can see Terranova’s film as itself an exercise in thinking-as-storytelling, bending existent genres as it experiments with new ways of storytelling.

It is thus fitting that the film ends with a black screen, devoid of any visual stimulus. The empty spaces are filled with Haraway’s voice as she narrates “The Camille Stories,” a chapter from her recent book Staying with the Trouble (Haraway 2016). This science-fiction story offers a rumination on a world in which a human child and monarch butterfly exist in biological symbiosis, forming and reforming kin, practicing what she calls “intensities.” The tale invites us into Haraway’s vision for a multispecies sociality, a way to “cultivate the arts of living on a damaged planet,” a phrase she borrows from Anna Tsing and her collaborators (Tsing et al. 2017). It is as if we have been primed by the film for this moment: to listen; to be with Haraway as she weaves the story; to enter its world; to inhabit an otherwise, even if just for a moment.

References

Biehl, João. 2013. “Ethnography in the Way of Theory.” Cultural Anthropology 28, no. 4: 573–97.

Haraway, Donna J. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm.

_____. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, Heather Anne Swanson, Elain Gan and Nils Bubandt, eds. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.