Substituting the Individual for the Collective in the Climate Crisis

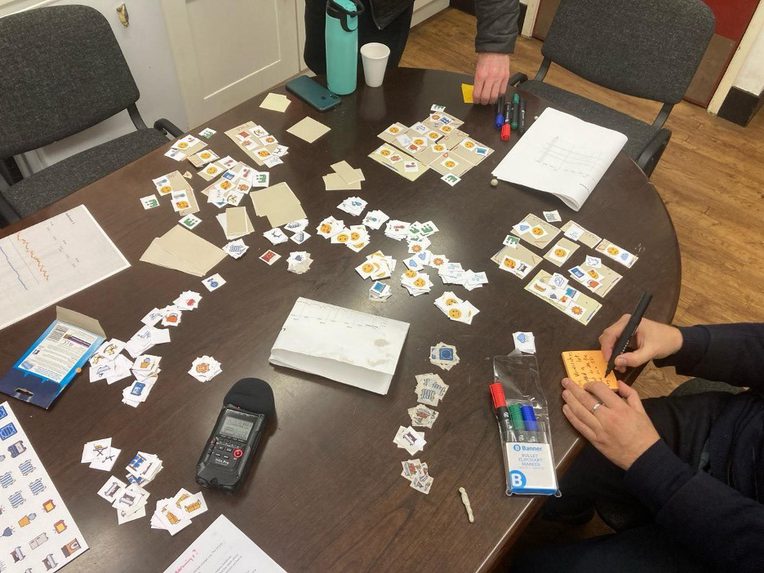

From the Series: Substitution

From the Series: Substitution

Climate action, from the global activism of Fridays for Future, to the UNFCCC COP summits, to government designs for a “green new deal,” hinges on the shared realization that climate change is a problem of collective social life. This collectivity is indexed in the inexorable rise in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere as the result of a range of disparate and disjointed practices, decisions, actions, ideas, ambitions, and inventions over decades, both enabled by and reliant on fossil fuel extraction and combustion.

The work of climate action thus pivots on a requirement to re-introduce novel conceptualizations of the collective in order to both understand the ontological contours of climate change, and to consider how it might be otherwise. However, it does so in the face of a legacy of acting and thinking which has long formulated answers to social problems through a commitment to the power, rights, and freedoms of the individual. Whilst climate action addresses a collective problem it often does so through an appeal to the individual: in the form of carbon footprint calculators, exhortations to eat less meat, and household smart meters. Proposals for more collective forms of action are in turn countered by fears of social control over the self, market protectionism and the stifling of innovation, and consumer choice.

In this essay we ponder on the intransigence of the original (the individual) in the face of an urge for substitution (the collective). To do so we present a situated attempt to decenter the individual as the ideal-subject, drawing on a project we have been involved in that explores the development of visualizations of domestic-level energy data to assist collective forms of climate intervention.

Digital visualizations of energy data are an important way in which the energopolitics of climate change have entered the domestic realm. “Smart” energy meters have proliferated alongside other data visualizations that draw attention to the energetic lives of objects—cars, buildings and appliances—highlighting their interactions with each other, people, and the grid. Designed by engineers and provided by energy companies, these visualizations are typically developed as tools to elicit individual and household-level behavior change in order to reduce consumption, and so help the climate.

In contrast, our interdisciplinary project Beyond Individual Persuasion has been working across the fields of human computer interaction, energy social science, and anthropology, to reimagine data visualization interfaces as mediations between energy and social collectives. The impulse for such substitution interacts in complex ways with the broader politics of climate change. Whilst some actors seek to find solutions that will ensure livable futures while maintaining established social patterns (imagining substitution as a more conservative act), others approach the climate crisis as an occasion for more fundamental transformation (imagining substitution more radically). We have thus attempted to reorient environmental sensing and visualization design away from the individual and towards the interests of distributed socialities such as organizational or government policies, community energy cooperatives, or local neighborhoods.

However, even with such a clear intention, the individual has remained remarkably resilient in our work. Take for example, a recent project from our team, exploring temperature and humidity sensing in people’s homes. There is nothing inherently individualistic about attending to these qualities, suggesting, in turn, that they might be visualized in ways that enable more collective understandings. Temperature is a socio-political issue. Coldness and dampness are the material outcome of leaky materials, bad design, lack of maintenance, and soaring costs of energy caused by geopolitical forces. Aberrant materialities like mold and rot, have the potential to manifest as indices of disempowerment, waste, decay, and failure. They can become markers of social opprobrium (manifesting in bodies as illness, depression, and fear), or triggers for political action to tackle rogue landlords, bad regulations or discriminatory energy politics.

Indeed, one research participant remarked that, living in the middle of a block of flats their home was heated by their neighbors, meaning her family never switched on their heating except on those rare occasions when temperatures dropped below -5˚ Celsius. Meanwhile, she believed that issues with persistently high humidity stemmed from the aging buildings and the refusal of the local authority–run management company to take accountability for maintenance and repair. For her, displays of temperature and humidity indexed the rhythms of other lives and wider socio-political concerns, as much as they did those within her household.

However, despite our attempts to design visualizations that encouraged people to attend to more collective horizons, we found that collective concerns continued to be articulated alongside more individualistic sentiments of preference, feeling, and desire. Participants frequently responded to our visualizations of energy use, temperature, or humidity in relation to personal experiences of comfort and discomfort, articulating how they liked their home to be, what their budget allowed for, and how their home heating related to their job, biography and lifestyle.

Whilst participants very often joined our studies out of an expressed concern for climate change, they also came to us as well-trained consumers of energy data visualizations, accustomed to thinking in terms of individual responsibility and conviction. Substituting individual action with collective sensibilities was not as easy as replacing one with the other—instead we found people moving back and forth between these different framings of energetic relations.

Economists distinguish inelastic goods—goods that are difficult to substitute, where consumers accept price changes or go without (oil and gas are textbook examples, evidenced by recent energy crises in the Global North)—from elastic goods, that are more easily substituted. For our purposes, however, it helps to invert this metaphor and think of elasticity as a tendency for people and things to resist substitution: when prevailing socio-political perspectives are displaced, the wider normative context causes them to quickly “snap back” to established states. Although visualizations of energy, temperature, or humidity may present open-ended possibilities for understanding collective dynamics, the wider context of possessive individualism means that intimations of collective possibility are “snapped back” to individualized concerns before being expanded again to considerations of the collective.

Substitution demands that people find ways of constantly maintaining productive tension between the original and the substitute, whilst striving to produce designs that “fit” and are usable within their lives. Substitution is not an act of replacement, but rather an intervention that destabilizes the status quo, with no guarantee of persistent and enduring change. This small example suggests that substitution demands an ongoing attentiveness to that which it seeks to replace, as well recognizing that the form of the substitute will itself be changed by its emergence in tension with that which preceded and continues to exist alongside it.