Surfacing

From the Series: Topology as Method

From the Series: Topology as Method

None of the Drung women I talked to could draw their facial tattoos on a piece of paper; it was not an image that could be abstracted, detached from its surface. One suggested playfully, though, that she could draw it on her granddaughter’s face. These women, who were in their sixties or older during my fieldwork in the early 2000s, had played in this way in their youth: although not just drawing but actually tattooing motifs on each other’s calves or forearms. They had vivid memories—the body itself remembered—of times when tattooing was in the order of things; before Communist authorities forbade it in the 1950s. In the remote Dulong Valley in Southwest China, tattooing (bāktūq) started even before the nubile age, as a form of reciprocal fashioning that took place between young girls via tattooing games.

The playful trial runs were a way of experimenting with the bodily experiences involved in the tattooing process: pain, bleeding, swelling, warmth. . . A gradual transition to a sort of social puberty leading to the irrevocable facial tattoo that will be performed by an older woman. The tattoo on the face was the continuation of cumulative actions, a transformative process that, in this society, prepared a woman for marriage and her role as mother. Indeed, the pain of the tattoo on the face was part of it, comparable to the pain of childbirth: an experience intrinsic to the becoming of a woman. The ink is an active agent in this process, made of soot scraped off the bottom of the cooking pot in which women cook family meals on the hearth—the very center of the house, a space of cosmic ties, and a symbol of matrimonial alliance.

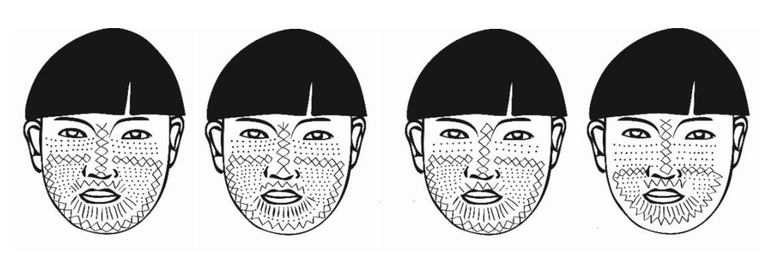

However, there was no requirement for the facial tattoo to be performed by a woman in a specific kinship position: the tattooist/tattooed relationship did not mirror the orientation of cross-cousin marriage prevalent in this society. Also, it became obvious that the limited geometric patterns of the tattoos were not intended to function as a symbolic system (if they ever did, this has been lost). The patterns were very stable and executed with only minor variations, a constancy paralleling the permanence of the tattoo itself (see Figure 1). Something else was going on between women, through the medium of the skin as a space of their own.

Drung women facial tattoos attest to the well-documented fact that forms of bodily adornment constitute a “social skin” (Turner 2012), an added but coextensive layer to this “fleshy interface” (Ahmed and Stacey 2001, 1) through which we engage with and experience the world, conduct our relationships, and display our identities. The multilayered and complex structure of the skin ensures the continuous communication of the interior world and the external one as it is both an inward- and outward-looking surface, our most fundamental sensory organ. Clearly, the tattoo is not simply onthe skin as if limited by its cartographic condition. A different kind of mapping is taking place.

I understood the Drung women saying that it was a process of surfacing, which culminated on the face as the most obvious interface: the penetration of the spine and the ink effected an emergence beyond ostension. On such a surface, the act of tattooing itself reveals an inside that “has been applied externally prior to being absorbed into the interior” as Alfred Gell (1993, 38) put it, in an interplay that exemplifies a form of continuity.

Space exists first by and through the body. Anthropology has repeatedly demonstrated—against popular preconceptions—that two bodies can occupy the same extent. If the body is an elementary form of the spatiality of life, then the skin is the organ with the most relational quality—a topological space that establishes contact between the most distant, the deep, the inside and the outside, relative exteriorities and interiorities, and that operates according to a multidimensional (gendered) corporeal code. In sum, facial tattooing among Drung women, as a process through which a particular fashioning occurred, instantiated a differentiation in each woman by unveiling her generative power that engaged her whole body as the site of an intersubjective actualization and intercorporeal participation.

This feminine space is not constrained by preexisting kinship positions (the geometry of kinship terms) but maintained through the generative force of a relational logic—a continuous reproduction of similarity that the tattoos effects, which itself is a condition for the production of difference through marriage and the inclusion in a cohesive kinship space. Each tattoo, seen through this relational lens, is a unique actualization but also a sign of belonging and relatedness, of what used to bind women together—tattoos should look like those of the elders. What seemed crucial for these women was how the face seemed to mediate a process of individuation through the permanence of the tattoo that stabilized the generative force of life as socially reproductive. Their facial tattoos were vectors of womanhood, a deeply gendered spatial logic in a system of relational configurations that is self-referential (every instance is the whole). In such a system, space and time are intrinsic and emergent; what appears distant can also be proximal; and transformations of the relations are immanent.

While facial tattooing among Drung women clearly played a role in producing a sense of selfhood, person, gender, and reproductive roles, its importance for the social reproduction of society is relative. Some women resisted the interdiction of the practice until the early 1960s, and a few also tattooed minimally on the chin. Nowadays they tattoo no more, altering the morphogenetic and topological virtualities of the feminine space.

Ahmed, Sara, and Jackie Stacey. 2001. “Introduction: Dermographies.” In Thinking Through the Skin, edited by Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, 1–18. London: Routledge.

Gell, Alfred. 1993. Wrapping in Images: Tattooing in Polynesia. London: Clarendon Press.

Turner, Terence. 2012. “The Social Skin.” HAU 2, no. 2: 486–504. Originally published in 1980.