This syllabus archive brings together a range of syllabi concerned with race and anthropology, with a particular focus on Blackness. Blackness is fundamental to the ongoing context of reckoning with the part anthropology has played, is playing, and could play in the future regarding constructions and deconstructions of racial ideology in the afterlives of slavery. We hope that curating these syllabi together and making them publicly accessible will highlight the ways anthropologists teach about race and interrogate anthropology's own relationship to anti-Blackness, white supremacy, anti-racism, and imperialism. These syllabi speak to core questions within cultural anthropology and the impossibility of interrogating those questions without close attention to histories and geographies of racialization: How can the history of anthropology be used to facilitate discussions about the construction and perpetual remaking of race and racism in the United States? How do the lived experiences of Black anthropologists shape the tools employed in ethnographic research and the audiences reached by their work? How can we broaden discussions beyond racial binaries to think about nuances of in-between positionalities and configurations of race outside the United States?

In compiling these syllabi, available for download below alongside an accompanying reflection from the course creator, a few themes stand out. A prominent one is the relationship between anthropology and history. Anthropology struggles with untimeliness (Rees 2018), as anthropologists historically produced the “Other” as an object of study by freezing them into the static past (Fabian 1983). Yet in these syllabi, we see an embrace of thinking the present historically. This includes the historical ways anthropology has produced discourses about race and the ways that anthropology of race is in constant conversation with historical change.

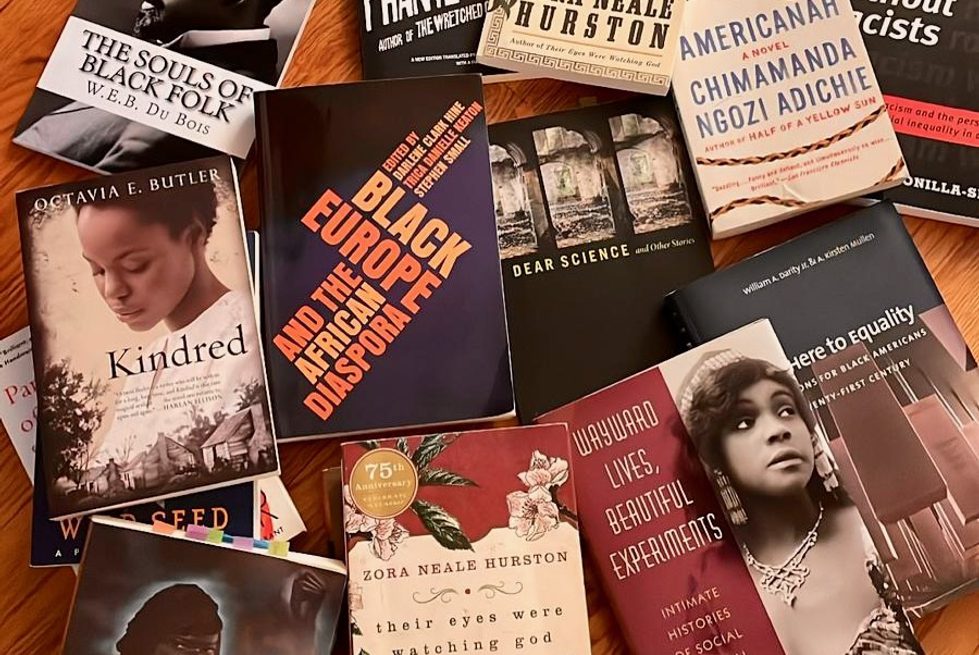

The syllabi also highlight the importance of using primary sources as pedagogical tools: asking students to read, for example, early twentieth century legal cases to examine the historical construction and legal/ontological instability of racial categories or to view Zora Neale Hurston’s footage. The syllabi refute boundaries between high/low culture or academic/nonacademic sources by centering artistic productions and visual culture as core texts, such as Amy Sherald’s portraits and Eve L. Ewing’s poetry. In this manner they decenter formal academic venues as the only site of intellectual work. They invite us to boldly engage the cultural phenomena and themes onto which Black anthropologists turn the “spyglass of Anthropology” (Hurston 1935, 1), particularly through reflection on the rigorous and radical contributions of African American anthropologists, interdisciplinary ethnographers, and researchers beyond academia.

Some differences also emerge with attunement to the role of place and culture in shaping constructions of race (hooks 1990). The courses explore how to teach racial ideologies as geographically varied. In this way they highlight the specificities of racial formations in the US, how they are embedded within—and sometimes even oppositional to—processes and legacies of racialization elsewhere. For courses taught in the United States, this approach helps students to both contextualize and denaturalize their understandings and experiences of race. Furthermore, these syllabi demonstrate anthropology’s ongoing engagement with Black feminism and intersectionality (Nash 2019), exploring race, gender, sexuality, and class across institutional sites, popular culture, and personal experience.

Lee D. Baker (Duke University)

Download “The Anthropology of Race” Course Syllabus

This has become one of my signature courses. In most courses, we try to achieve learning outcomes. In this course, I try to achieve “unlearning” outcomes. I structure it around the three segments of the PBS documentary “Race: the Power of an Illusion,” which is over twenty years old, but still pretty good. The first section breaks down race as a social construct, the second looks at the history of anthropology, and the third looks at anti-black racism today. I throw a ton of original documents ranging from drafts of the declaration of independence to a PlayBoy Magazine interview of American Nazi George Lincoln Rockwell. I think it works well because students have an opportunity to discuss challenging ideas or debate approaches over the course of fourteen weeks. So they get to know each other and begin to trust each other and develop empathy, which is certainly a rewarding outcome.

Tracie Canada (Duke University)

Download “Black Ethnographers” Course Syllabus

What is ethnography, broadly defined? What tools can be used to describe a particular social world? What audiences exist for an ethnographer’s finished product? How does one’s lived experience as a Black person in the United States affect the ethnographic work produced? These are the questions that guided “Black Ethnographers,” a course I had the opportunity to teach during both semesters of the 2021-22 academic year, when I was a faculty member in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame.

Cross-listed with Africana Studies, Sociology, and American Studies, students in this course learned how an in-depth study of ethnography, through the perspective of Black scholars and thinkers, presents different techniques, products, approaches, theories, and texts. Ethnography has been important to Black scholars across the social sciences, but especially in anthropology—as they grapple with issues of anti-Black racism, imperialism, and colonialism—given it’s an approach that takes seriously the people who are central to the research and allows for them to theorize their own lives and speak for themselves.

I developed this course to introduce students to the creativity allowed by the ethnographic method, but also to show the number of contemporary scholars who are engaging it. Disciplines tend to systemically privilege and canonize scholars in a way that overrepresents the scholarship of white, male, heterosexual, cis-gender thinkers. I’ve written about this issue across multiple essays in History of Anthropology Review. I counter this narrative and decanonize this syllabus by assigning only Black theorists, many of whom are living and relatively junior in their careers across fields and disciplines, who often champion social justice, anti-racist, and anti-colonial praxis in their own work. The first quarter of the course lays the theoretical foundation for ethnography as central to anthropology. The middle half of the course provides examples of different approaches to ethnographic texts, including digital ethnography, photography, dance, poetry, and music. The last quarter of the course includes public facing works by Black anthropologists and scholars in other disciplines to highlight that the audiences and publics for these intellectuals are rarely ever just in the academy.

Lanita Jacobs (University of Southern California, Dornsife)

Download “African American Anthropology” Course Syllabus

This seminar is my humble and heartfelt tribute to African American anthropologists and the robust field we inhabit. Many of the assigned articles are intentionally drawn from our field backed by seminal texts that bespeak the many ways African American scholars and African American culture writ large duly and steadily inspire the field of anthropology today.

Download “African American Humor & Culture” Course Syllabus

Created this ambitious “boutique” course (i.e., one that serves your research and curricular needs) because I wanted to find a way to bring African American comedians as (humbly) paid guest speakers to my course and catch myself up as a then bourgeoning scholar of humor studies with anthropology steadily in hand.

Download “Exploring Culture through Film” Course Syllabus

Each faculty member in University of Southern California’s (USC) ANTH department approaches this general education (GE) course in their own way; I approach it as a primer in Cultural Anthropology (largely) from a “native” anthropologists’ perspective.

I created this seminar turned GE course with USC’s enthusiastic support shortly after 9/11. Then, it was called: Collective Identity & Political Violence: Representing 9/11. A central motivation was to (again) bring Black comics to USC as (again, humbly paid) guest speakers, but students and socio-political context had a greater role in shaping this course’s heady ambitions and trajectory. So, too, did the occurrence of Hurricane Katrina, which I formally integrated into the course title later on (i.e., Collective Identity and Political Violence: Representing 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina) to stage critical explorations and conversations around race and nationhood that might otherwise be missed if one solely focused on the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

Kaifa Roland (Clemson University)

Download “Brown Studies” Course Syllabus

I asked one of my doctoral students, Dr. Bailey Duhé, what course she wished to take that was not available. As a bi-racial student, she had always wished for something that didn’t just focus on race as a black and white issue but on racial mixture. She then created the course as an independent reading. I taught it for two iterations to bang out the kinks, and it is now one of her standard courses. It was designed to have a toolkit component so that students would create and work through content on their own to maintain for future use. Based on in class feedback and evaluations, the course was a resounding success each time it was taught, though I felt the second time was smoother.

**Update: A previous version of this post failed to credit Dr. Bailey Duhé as the creator of the Brown Studies course. This post has now been updated to include correct attribution.

Download “The Caribbean in Post-Colonial Perspective” Course Syllabus

This is the course I teach most frequently, and my favorite to teach. It was designed as an introductory course for first or second year students who likely have no exposure to anthropology and may never take another anthropology course again. It was designed to de-center the European and U.S. perspective on the history of the Americas and center the Caribbean by asking: What does the world look like from a Caribbean-centric perspective? How is race constructed distinctly? How is the Caribbean a factor in and feature of globalization?

As I said, this is and will always be my favorite course to teach. I like introducing large numbers of students to the beautiful peoples and cultures of the Caribbean. I use lots of music and films to bring the people in place to life. My favorite thing in the world is to teach about the importance of Haiti to the path and progress of the world. The course gets great reviews because there are elements of things they are familiar with but were never asked to think about critically before, so you really get to see lightbulbs go off as they use an anthropological lens to make sense of things.

Download “Cuban Culture: Race, Gender, Power” Course Syllabus

This was the very first course I designed when I was still a graduate student. It has been trimmed, expanded, and re-visited over the years of changes in Cuba. The first time I taught it, evaluations said it had too much race in it, so I put it in the title to make sure students know race (and gender) would be centered. It begins with a historical lens on race and gender and moves toward the present post-Soviet period. The latter part of the course is where most of the changes regularly occur. While I enjoy teaching the course, students’ interest in Cuba fluctuates with how much it is in the news, so I am often concerned it will not fill. I now teach it most consistently when I am about to lead a study abroad to Cuba so that I am confident there will at least be a core cohort, both for the class and the study abroad.

Download “Anthropology and Race” Course Syllabus

Like the Brown Studies course, when I first began teaching at the University of Colorado-Boulder, I asked the graduate students what they felt they were missing in their graduate education that I could provide them. A seminar on race was the response so that is what I created. I approached the course by pulling the race content I had been gathering for myself over the years since graduate school that felt relevant to my anthropological understanding: dialogues between Boas and DuBois, the first waves of black anthropology students and how they were often exiled to other disciplines, radical thinkers from the edges who pushed the discipline to decolonize and may have been forced out of the academy in the process. And of course contemporary race theorists and theorists of color. The course ends with readings student contribute with whom I or others may not be familiar that may filter into future iterations of the course. Like most of my courses, the evaluations and feedback is that all anthropology grad students should have had to take the course. The last time I taught it, it was as a Bridging Seminar co-taught with a biological anthropologist.

Download “Zora Neale Hurston, Anthropologist” Course Syllabus

When I was an undergrad at Oberlin College, I took a course with bell hooks/Gloria Watkins on Zora Neale Hurston that taught pretty much everything Hurston had every published. I had never taken a course that focused exclusively on Hurston as an anthropologist. She was always just mentioned as a black anthropologist but then discarded theoretically. I wanted to change that so I revived Dr. Watkins' course (and added subsequent readings as they were published). I begin the course with her autobiography, then move to her Mules and Men research from her time at Barnard, then Tell My Horse from her Caribbean research that is seldom discussed at all. I then move to her novels and demonstrate how she is an experimental ethnographer before the discipline ever recognized it as a category in that she is doing the same ethnographic work in her novels but without feeling bound by the disciplinary structures that likely bound her too tightly. Now that I have taken a position outside of anthropology, I am enjoying this freedom myself! Though the course occasionally had to drop because it didn’t always fill, the last few times I taught it, the room was overflowing with students. The key is not to offer it too frequently (every two to three years). Students absolutely love the course, especially since it concludes with an “Eatonville Party,” where we bring foods mentioned in her works.

References

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

hooks, bell. 2009. Belonging: A Culture of Place. New York: Routledge.

Hurston, Zora Neale. 1935. Mules and Men. Philadelphia: J.B Lippincott, Inc.

Nash, Jennifer C. 2019. Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Rees, Tobias. 2018. After Ethnos. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.