Tamsaling and the Toll of the Gorkha Earthquake

From the Series: Aftershocked: Reflections on the 2015 Earthquakes in Nepal

From the Series: Aftershocked: Reflections on the 2015 Earthquakes in Nepal

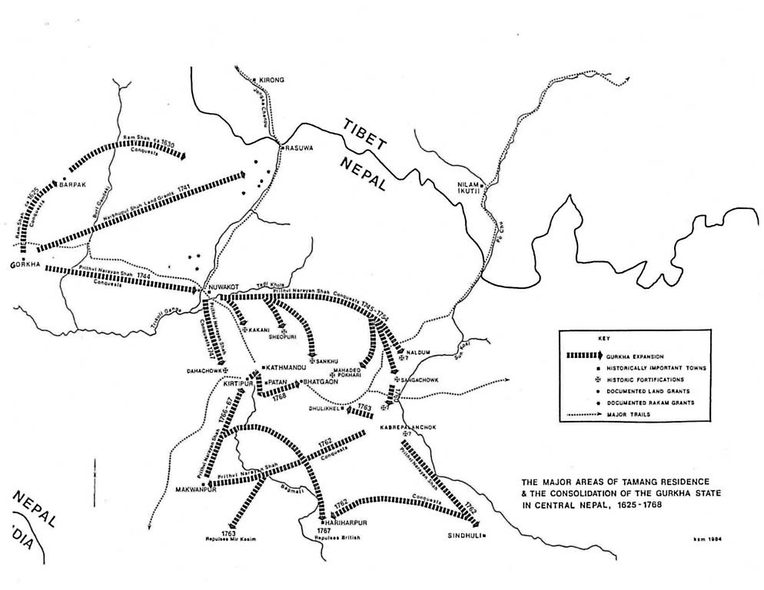

History, like earthquakes, recurs at merciless intervals in the homelands of the Tamang in north central Nepal. Military conquest, government intervention, and cultural dissonance have repeatedly battered this region. The Gorkha earthquake of 2015 were, just as surely, a Tamsaling tragedy.1 Both NGOs and local observers have pointed out that the effects of the earthquake were exacerbated by the social, political, and economic history of exploitation and exclusion that has marked this region over centuries. Just as in the past, local Tamang will have to rely mostly on their own resources to rebuild, hoping that outsiders do not make their task more difficult.

The unequal impact of earthquakes is a legacy of the Shah conquest, which rewarded loyal retainers with land grants that turned the indigenous cultivators into second-class tenant-farmers (Tamang 2009). It would fall to these cultivators to “do work” (kam garnu), not only to feed themselves but also to support elites, who were able to “eat jagir” (rents, entitlements, and ultimately salary). This impoverished local people and gave rise to the idea that winning senior positions in military and civil service was not work, but rather a reward that entitled beneficiaries to live comfortably from the work of others. Entitlements enabled elites to live sumptuously, with luxuries like cars literally carried on the backs of others. The Rana regime intensified the internal colonization of Tamsaling with increasingly elaborated forms of compulsory, uncompensated labor (Holmberg and March 1999).

Central elites and administrators were caught in a different kind of bind. Instead of salary, they vied for the favor of their rulers in order to be granted control of the resources that the state claimed the right to regulate. Theirs were the shares over and above whatever they had to convey to their superiors. To eat jagir by skimming from the resources they controlled meant ingratiating superiors and treating those who worked as inferior, a clear precursor to the modern problem of graft.

A uniquely Tamang perspective on this history of exploitation can be found in a myth about the construction of the Samyé Buddhist monastery in Tibet and its role in local exorcism rituals. In the original myth, devout locals built all day, every day, only to discover each morning that demons had destroyed their work in the night. The Phykhuri Ridge performance of the myth includes dramatic strategies for capturing and exorcizing these demons, with the twist that the demon who makes local Tamang suffer is Kali Mai (Durga), protectress and symbol of the Shah monarchy (see Pfaff-Czarnecka 1993; Holmberg 2000). The ritual is explicit: Kali Mai is not welcome on Phyukhri Ridge. She brings only suffering, and she would do well to return to the Taleju Temple complex in Kathmandu.

In response to central elites siphoning off labor and resources, Tamang intensified a distinctive set of their own practices. In rituals, as well as in daily practices like wearing unique dress (see March 2000), acting “dumb,” and failing to maintain trails, Tamang attempted to seal themselves off from the extractive incursions of outsiders and to recuperate their own values of kin-based reciprocity. Cross-cousin marriage, in particular, weaves ties of mutual obligation through Tamang communities that have counterbalanced asymmetries based on wealth, chance, or relations with the state. Tamang society is founded upon these ideals of reciprocity, not those of hierarchical entitlement.

As Nepal developed, hierarchical and extractive elite practices came to constitute the legitimate machinery of the state. Thus, the very fabric of governance in Nepal has historically impeded local development, a point made manifest by the fact that more resources—from roads to family planning—came to Phyukhri Ridge during the years of the civil conflict than ever before. This is because there was no government presence to obstruct the free circulation of energy and capital—both monetary and cultural—within local Tamang reciprocal relations.

1. Tamsaling is the name that most Tamang want to be given to an as-yet-undelineated federal province that would recognize their historical residence there.

Holmberg, David. 2000. “Derision, Exorcism, and the Ritual Generation of Power.” American Ethnologist 27, no. 4: 927–49.

Holmberg, David, and Kathryn March, with Suryaman Tamang. 1999. “Local Production/Local Knowledge: Forced Labour from Below.” Studies in Nepali History and Society 4, no. 1: 5–64.

March, Kathryn S. 1983. “Weaving, Writing and Gender.” Man NS 18, no. 4: 729–44.

Pfaff-Czarnecka, Joanna. “The Nepalese Durga Puja Festival, or Displaying Political Supremacy on Ritual Occasions.” In Proceedings of the International Seminar on the Anthropology of Tibet and the Himalaya: September 21–28, 1990, 270–86. Zurich: Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich.

Pigg, Stacy Leigh. 1992. “Inventing Social Categories through Place: Social Representations and Development in Nepal.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 34, no. 3: 491–513.

Tamang, Mukta S. 2009. “Tamang Activism, History, and Territorial Consciousness.” In Ethnic Activism and Civil Society in South Asia, edited by David Gellner, 269–90. London: Sage.