This post builds on the Openings and Retrospectives collection “Theorizing Refusal,” which was published in the August 2016 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

The collection brings together four researchers working on the topic of refusal, which they seek to theorize as “an ethnographic, as well as political, concept.” This Teaching Tools post offers some ways to explore the individual articles and their themes, while also examining how it is that refusal might be understood as a distinctly ethnographic concept. It is intended for use in upper-level undergraduate or graduate courses.

Learning Objectives

- To examine the boundaries between the concepts and practices of refusal, resistance, and abstention, with a view to developing a better understanding of where these notions overlap and where they maintain their differences.

- To begin to outline how anthropological or ethnographic understandings of refusal, resistance, and abstention compare to those used in political theory and political science.

Guiding Questions

The questions below may be used as initial discussion questions, or can just be kept in mind throughout the session. To facilitate this, the instructor might choose to write these questions on the board at the start of class.

- What are the differences between refusal, resistance, and abstention, and where do they overlap?

- What is the relation of each of these ideas to one another? Are they interdependent on each other for context and meaning, or do they maintain a level of conceptual and practical autonomy?

- What is it that marks an ethnographic understanding of refusal?

- What makes a concept an ethnographic one?

- How does such an understanding of refusal differ from understandings offered by political theory?

Exercise

Before class, students should have read at least one selection from each of the Further Reading lists below so that they can make comparisons between different disciplinary approaches. One of the exercise’s aims is to draw out the way in which anthropological approaches might be said to complexify relationships between resistance, refusal, and abstention. For instance, in political theory, the object of resistance is often understood to be the state or capital, while an anthropological approach may reveal more nuanced and specific power relationships at work.

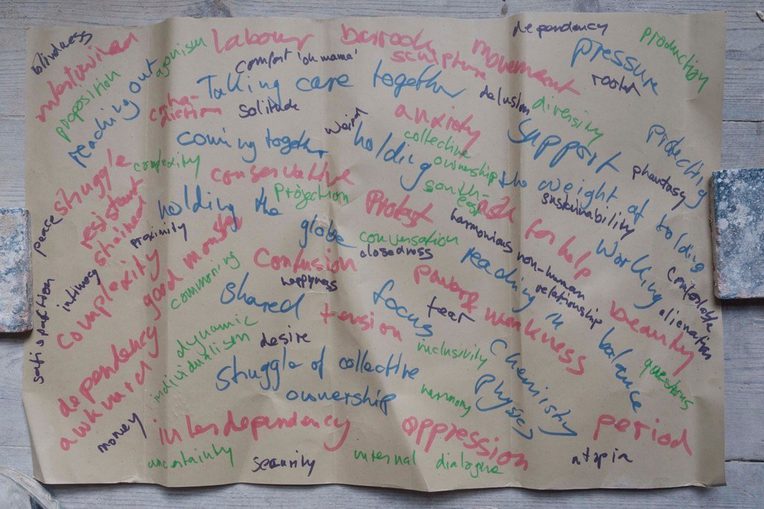

Start the exercise with three large sheets of flip-chart paper, laid out on three tables with a selection of colored markers. Leave enough room between the tables for students to move around them. One sheet should be labeled Refusal, one Resistance, and one Abstention.

Ask the students to write a few words about what each of these concepts entail on each of the sheets of paper, so as to collectively develop a mind map of each term.

Sitting in a circle with the mind maps on the floor in the center, go through each of the maps as a class and discuss them with a view to locating overlapping themes, as well as areas of difference and distinction. Record the resulting areas of differences and overlap, or ask a student to serve as the recorder so that the instructor can focus on facilitating the discussion.

Finally, divide another sheet of paper into three columns. The left and right columns should be labeled “Anthropology/Ethnography” and “Political Theory/Political Science.” The heading for the centre column can be left blank.

Move into a discussion about how anthropology and ethnography would approach examining the areas of difference and overlap identified by the class. How, in turn, could political theory and political science examine them? Record the responses under the relevant heading, reserving the middle column for points of overlap between the two disciplinary approaches.

Further Reading

Anthropology and Ethnography

Graeber, David. 2013. “Culture as Creative Refusal.” Cambridge Journal of Anthropology32, no. 2: 1–19.

McGranahan, Carole. 2010. Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Ortner, Sherry B. 1995. “Resistance and the Problem of Ethnographic Refusal.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 37, no. 1: 173–93.

Seymour, Susan. 2006. “Resistance.” Anthropological Theory 6, no. 3: 303–21.

Simpson, Audra. 2007. “Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship.” Junctures: The Journal for Thematic Dialogue, no. 9: 67–80.

_____. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States.Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Sobo, Elisa J. 2015. “Social Cultivation of Vaccine Refusal and Delay Among Waldorf (Steiner) School Parents.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29, no. 3: 381–99.

Weiss, Erica. 2014. Conscientious Objectors in Israel: Citizenship, Sacrifice, Trials of Fealty. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Political Theory

Berardi, Franco. 2003. “What is the Meaning of Autonomy Today? Subjectivation, Social Composition, Refusal of Work.” Republicart: Real Public Spaces, September.

Federici, Silvia. 2012. “Wages Against Housework.” In Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle, 15–22. Oakland, Calif.: PM Press. Originally published in 1975.

Frayne, David. 2015. The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work. London: Zed Books.

Holloway, John. 2002. Change the World Without Taking Power: The Meaning of Revolution Today. London: Pluto Press.

Tronti, Mario. 1965. “The Strategy of Refusal.” In Autonomia: Post-Political Politics, edited by Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi, 28–35. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).