Editor’s Note

This feature of the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project (SECASP) in the Visual and New Media Review gathers the perspectives and framings of some of the project's core partners and advisory committee members. Just as contributor Chris Boebel notes how the project’s interactive scrapbooks should be taken as mediated selections of a broader whole, we might approach these vital commentaries similarly—I’d encourage readers to explore the rich online archive in full beyond this piece, and if visiting the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum in person, to draw on the SECASP in making connections between objects in the physical collection. Countering the tendency towards ossification of traditional archives and museum collections, as contributors note, the SECASP premises object-led approaches to telling immersive stories. As a platform, the SECASP serves as a living, up-to-date, community-led historical repository of Southeast Chicago. In the following feature, its contributors elaborate upon the pedagogical import and political urgency of documenting and sharing such understandings of the region, impressing upon us their salience to the survival and hopes of the community.

-Jill J. Tan, ed.

Introduction

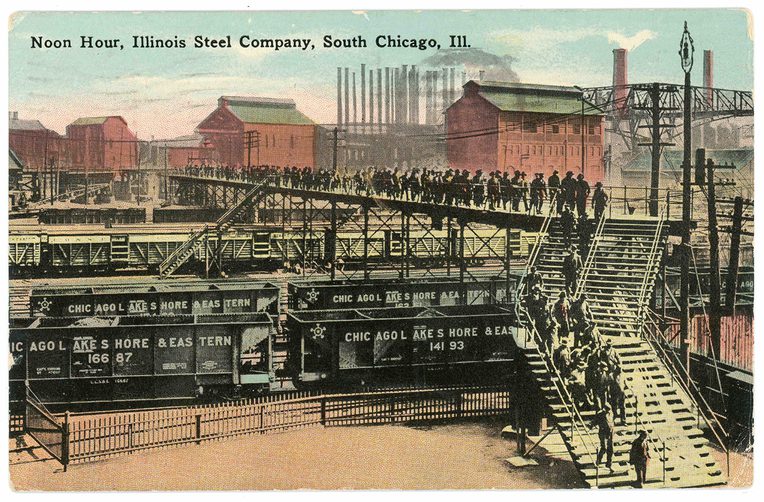

The Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project (SECASP) is an online collaborative venture ten years in the making. It highlights materials donated to the all-volunteer Southeast Chicago Historical Museum by the diverse working-class residents who settled in this former steel mill region. This multimodal project uses residents’ saved objects—and the stories they told about them—to bring to life everyday experiences of work, immigration, job loss, and environmental contamination from their own points of view. It understands storytelling around objects to be key to cross-generational conversation both within working-class communities and beyond, laying the groundwork to help residents (and others) imagine futures that both build upon and transcend this simultaneously rich yet troubled past. The project began after anthropologist and former Southeast Chicago resident Chris Walley and filmmaker Chris Boebel proposed a collaboration to museum volunteers and Director Rod Sellers. The website sechicagohistory.org includes four innovative mini-documentaries or “storylines” in addition to an online archive. The site has been created by a project team, including creative director Jeff Soyk, in collaboration with Museum volunteers and community residents, and it is overseen by an advisory committee.

Chris Walley

Chris Walley is a former Southeast Chicago resident from a steelworking family. Chris is the Director of the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project and a Professor of Anthropology at MIT. She began exploring the history of the region for the auto-ethnography Exit Zero: Family and Class in Postindustrial Chicago (2013) as well as in Exit Zero: An Industrial Family Story (2017), a documentary directed by filmmaker Chris Boebel.

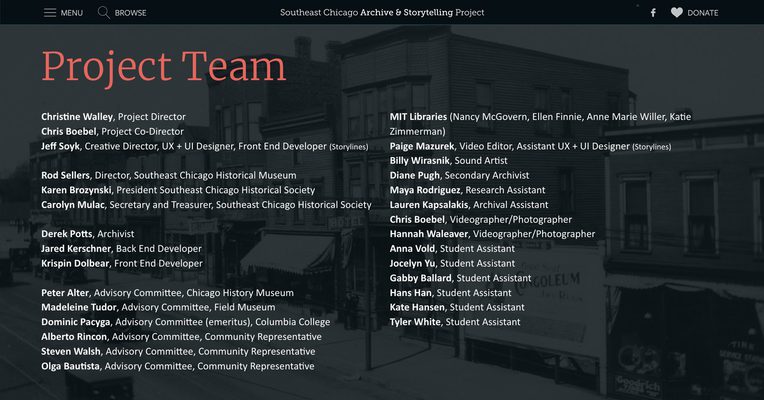

Walley writes: For most of us, it is saved objects and images—and the stories we tell about them—that make history. The Southeast Chicago Historical Museum houses a remarkable collection of photos, home movies, scrapbooks, documents, letters, clothing, objects, and more items, donated by diverse groups of Southeast Chicago residents for over forty years. These materials include: a young immigrant’s World War I diary filled with romantic longings and Polish drinking songs; the World War II era steel mill badge of a mother who fled village violence in the wake of the Mexican Revolution; and home movies that steelworkers made of the mills in the 1990s before their demolition. This Museum represents a unique repository created and curated by working-class residents and former residents. As the steel mills that defined Southeast Chicago for a century began to close, many residents countered a sense of history slipping away by donating items they found meaningful to this community-based Museum, hidden in a single overstuffed room in a park fieldhouse along a forgotten stretch of the city’s lakefront.

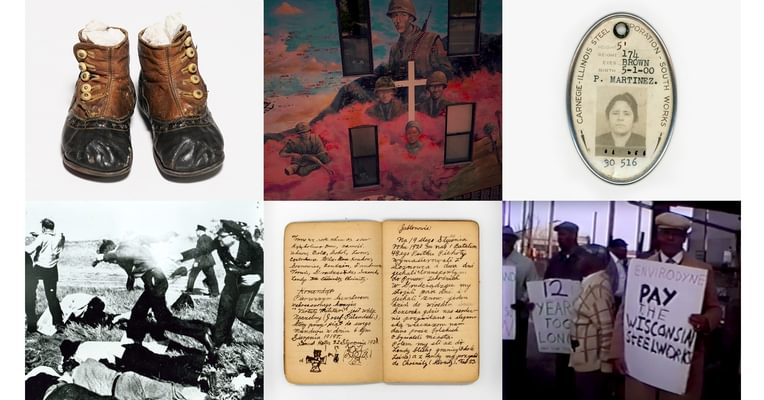

The Museum holds personal history for me. I first visited it with my father when I was a teenager. Like many unemployed steelworkers in the 1980s and 90s, my father would wander over to the park to help pass the long days after the mills had closed. In the Museum’s collections were objects saved by my own family members: church memorabilia donated by my mother, images of industry donated by a great-aunt, and photos of the 1937 labor event known as the Memorial Day Massacre that depicted my grandfather, neighbors, and hundreds of other hopeful unionists being shot at by police. While many residents, like my father’s mother, were descendants of Eastern European immigrants, other groups, including blacks and Mexicans, began arriving after World War I. (The region is now predominantly Latinx).

Museum materials offered me, as a budding anthropologist, key history lessons. These objects conveyed a visceral sense of what everyday life felt like for residents of an industrial region as both mills and jobs (but not the pollution) disappeared. These materials also offered insights into what linked working-class groups of different races and ethnicities together—and what tore them apart—from struggles over jobs, housing, and strike-breaking to intermittent alliances around labor and environmental activism to bonds (both generated and denied) through kin networks, schools, and churches. Martha Langford (2001) has argued that albums and scrapbooks are primarily oral, rather than visual, technologies and are meant to be handled in ways that elicit storytelling and conversation[1]. Placing scrapbooks in Museums, she suggests, suspends those conversations. If so, the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project is an online tool designed to reanimate those suspended conversations. It asks us to use these objects and stories as opportunities to reflect on aspects of the past that continue to trouble the present—oppressive working conditions, racial trauma, economic inequality, and environmental degradation—as well as on everyday experiences of fun and social vitality that gave and give life meaning. We have attempted to reanimate these conversations in ways that encourage visitors from other regions and backgrounds to also reflect upon and join in this collective discussion.

Steven Walsh

Steven Walsh is a SECASP advisory committee member and mediamaker. He is currently finishing a documentary film, SOUTHEAST: a city within a city, which explores the region through the experience of his Latino grandfather, who is a former steelworker, musician, and gangster/philosopher.

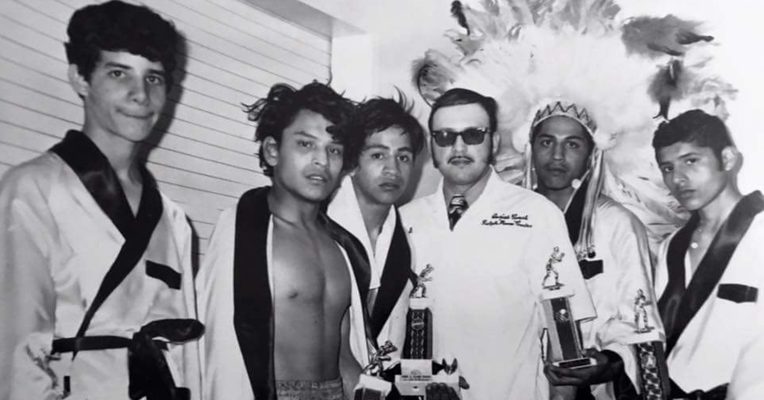

Walsh writes: I was born and raised on the Southeast side, and my film focuses on the rise and demise of the community—how beautiful it once was, and how that beauty was taken away, due to deindustrialization and an overall disinvestment in the area. As part of my filmmaking process, I reached out to the community to collect archival photos and video to showcase in the movie, including this photo of the Our Lady of Guadalupe boxing club circa 1970’s (Figure 8) to which Southeast Chicago's Golden Glove finalist Louis Aguilar belonged. This effort, in turn, connected me with SECASP, and since then I have been working side-by-side with the team to uncover more archival media and further preserve the neighborhood’s history, focusing primarily on the Black and Latino communities. As a community representative on the advisory committee, I hope to connect Southeast Chicago’s deeply rooted history to its effects on its present state.

Jeff Soyk

Jeff Soyk is Creative Director, UX & UI Designer, and Front-End Developer (Storylines) for the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project. He is an award-winning media artist and MIT OpenDocLab fellow alum. His work includes Hollow (2013), PBS Frontline’s Inheritance (2016), and Zeki Müren Hotline (2021).

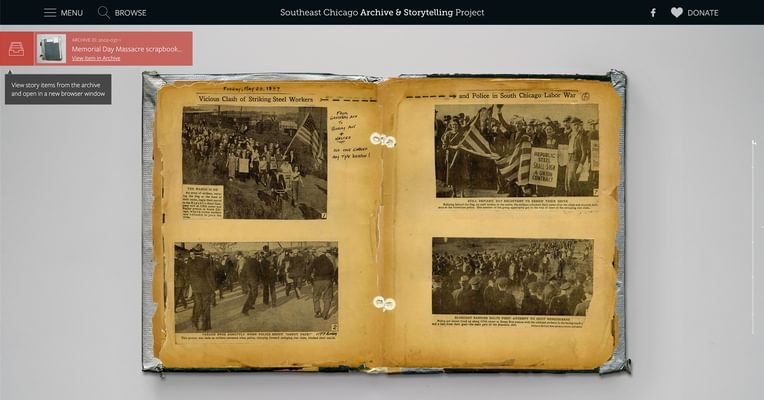

Soyk writes: I have always been fascinated by the objects we choose to save, and the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum is clearly not in short supply. It is packed with profound and intimate objects that offer a unique perspective into life in that region. Yet, as a visitor, forming connections between objects can be challenging, especially given the quantity and breadth of the resident-donated materials. This is where the “Storylines” section of the SECASP website comes in. “Storylines” are immersive stories told in the form of an “interactive documentary”—essentially a documentary that is created using the interactive web medium. They weave museum objects together to tease out their meaning and to build a narrative for website visitors to explore. Each storyline merges photographs, videos, oral histories, historical text, and soundscapes, to create a story experience built on the memories and emotions so vividly expressed in the archive materials. Upon entry into a storyline, visitors are introduced to a single object of interest that is related to a contemporary resident. In the Memorial Day Massacre storyline, for example, we are introduced to Mike Borozan in the present day as he holds a 1930s scrapbook in his hand. Mike is the son of the creator of that scrapbook. This has allowed the “Storylines” team to address the relationship between past and present and to involve local residents in the storytelling process. We also expect these storylines to engage current and future students in a classroom setting, not only to provide insight into the region’s history, but to open up larger conversations around the themes and topics addressed. The Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project has provided an incredible opportunity to get these materials out onto a bigger stage and to consider what we can learn from their examination and preservation.

Chris Boebel

Chris Boebel is Director of Media Development at MIT Open Learning, and he teaches classes at MIT on virtual reality (VR) and documentary film. A filmmaker by training, he is the director of Exit Zero: An Industrial Family Story and award-winning feature films, documentaries, and television programs. His work has been shown on PBS, the BBC, and at more than 50 film festivals.

Boebel writes: To me, this scrapbook created by Gerry Jolly Borozan (Figure 12) is one of the most powerful objects in the Museum collection. Scrapbooking is a very familiar activity for me, pursued by many members of my own Midwestern family. My family’s scrapbooks usually commemorate important life events like births, marriages, or graduations. Gerry’s scrapbook commemorates a massacre. It’s the lead object from the Museum collection that takes us into the storyline about the Memorial Day Massacre, a key event in community—and national—history. On May 30, 1937, striking steelworkers from Republic Steel were attacked by police as they peacefully picketed in front of the plant gates. Ten workers died, and around one hundred were injured in one of the bloodiest days in U.S. labor history. Gerry was seventeen at the time, and her house was right next to the field where the Massacre occurred. Her brother and fiancé were both mill workers, and all of them were present when the police started shooting. Gerry’s carefully curated collection of news clippings and other mementos are an important window into the story of the massacre, and her handwritten annotations bear powerful witness and remind us of how personally it affected her.

The scrapbook also led us towards our own storytelling process in the “Storylines.” Each storyline is an arrangement of artifacts from the Museum—a “media scrapbook” in a sense—and I think it’s important to understand them first and foremost as selections from a larger whole. The Museum collection in its entirety is about the Southeast Chicago community telling its own story, since the collection is created and curated entirely by community members. When we arranged objects into storylines, each one is always linked back to the Collection—that’s the salmon-colored tab in the upper left corner of the image (Figure 12). So even in the midst of a specific story, you’re never far from knowing an individual object’s place in the larger Museum collection. The very last pages of Gerry’s scrapbook document how she shared the story of the Massacre through the scrapbook itself at the 60th Anniversary on May 30, 1997. Once again, I believe Gerry's scrapbook guides us to the purpose of the entire archiving and storytelling project: to help unlock the power of these objects to understand, remember, and create continuity between past and present.

Olga Bautista

Olga Bautista is Director of the Southeast Environmental Taskforce, as well as a community resident and mother. She is also an advisory committee representative for the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project. This image shows Olga, holding a jar of petcoke (an industrial pollutant), standing next to her daughter Liberty.

Bautista writes: One of the key stories to tell about Southeast Chicago is the history of environmental pollution and activism in the region. The way we organized when industry was growing, and there was a sense of possible prosperity for all, is decidedly different from the organizing we do today, which is mainly for survival and protection from an economic system that seems hellbent on killing me and my community. In the post-industrial age, the large, sprawling factories spewing out pollution are dead hulls scarring the horizon of my community. Many families feel the scars of that period and reel from long standing health issues that still impact us today. We have folks who have never recovered from the series of economic after-shocks, from loss of income, loss of access to healthcare, and foreclosure. We are met instead with the inundation of dirtier, more polluting industries, whose promises of providing jobs do not materialize, and ultimately only end up hastening our exposure to even more diabolical and deadlier practices that continue to contribute to toxic air, toxic water, and toxic soil.

The inequities of the City of Chicago’s development and underdevelopment practices are as clear as the sky is blue. On one hand, there are developments near gleaming downtown which receive over a billion tax dollars for redevelopment. And, on the other, in our community, the old U.S. Steel’s large swath of land along the lake cannot get the investment needed to remediate contaminated parcels. We are a community that is in perpetual fighting mode for clean air to breathe. We have some of the highest levels of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and heart disease in comparison to other industrial corridors and the city of Chicago as a whole. We want jobs in this community that won't make our community members sick. We deserve better. Thanks to the leadership of everyday impacted people, we are working to hold polluters and city agencies accountable, and demanding development rooted in sustainability and restorative justice. The in-process website storyline called “From Wetlands to Waste” tracks the long legacy of environmental pollution and activism in Southeast Chicago, brings the history of the region up to the contemporary moment, and highlights the kind of future we’re trying to create for our kids and for our beloved community.

Rod Sellers

Rod Sellers is the volunteer Director of the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum and has deep roots in Chicago’s Southeast Side. Like many who historically resided in the region, his mother’s family immigrated from Poland. Rod was a local high school teacher for thirty-three years. He developed a “Museology” program, in which local high school students interned at the Museum, researched and developed educational booklets, and helped conduct many of the oral histories now at the heart of the collection.

Sellers writes: The SECASP Study Guide portion of the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project is designed to provide additional information and resources for teachers, students, researchers, and anyone who wants more information about Southeast Chicago history (see Figure 14 to see a screenshot of the website). It includes a comprehensive bibliography, links to other websites, a toolkit for educators with suggested activities and projects, and samples of three student-created booklets suitable for classroom use. The student booklets were created in the 1990s by the Museology program using materials in the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum—they include: A Southeast Side Tour, An Environmental History: Industry vs. Nature, and Cultural Institutions: A Community of Churches. Materials in the Study Guide may be used in classrooms studying subjects from literature to history and touching upon such topics as industrialization, immigration, labor history, urbanization, deindustrialization, and the environment. For biology and chemistry education, classes might even use these neighborhoods as a laboratory for studying environmental damage caused by industrialization and waste disposal. Encouraging students to explore community history in this way provides an excellent starting point for improving the relationship between schools and neighborhoods, while also offering community service opportunities. We hope that the Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project can serve as a model for other regions, one that allows local history to come alive while giving students opportunities to link daily experiences—both their own and those of previous generations—to the broader regional, national, and international events that we more commonly think of as “history.”

Footnote

[1] Thanks to Prof. Steven High for recommending the book and helping articulate this formulation of the website’s goals.

References

Langford, Martha. 2001. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.