The Afterlife of Images

From the Series: Self-Immolation as Protest in Tibet

From the Series: Self-Immolation as Protest in Tibet

CONTENT WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGES

Self-immolations draw attention to a cause and rally support in part because of their powerful visual imagery.[1] Seemingly everyday images of and about self-immolation by Tibetans are created and circulated online, particularly with the wave of incidents in the past six months that now total thirty-three cases.[2] And yet, as of the forgone Tibetan New Year of 2012, it may surprise some to learn that documentary photography and videos of self-immolation or its immediate aftermath have been published outside of Tibet for only seven acts since 2009.[3] A cycle of transnational circulation only then begins. Raw videos and photographs – of self-immolation, protests, mourners, and journalists’ furtive recordings – are smuggled out of Tibet to be posted on the websites of Tibetan and mainstream news channels and organizations, from which they are sourced for a variety of media, across the globe.

The self-immolation of thirty-five year old nun Palden Choetso in Tawu, Kham on 11 March 2011 and her funerary rituals are the most extensively documented. One video begins, unsteadily at first, with Choetso standing still on the street engulfed in flame. Shouting can be heard. A single woman in a Tibetan chuba dress walks from the sidewalk towards the curb, a long white khatag scarf in her hands. As she raises her arms to throw the khatag toward the blaze, Choetso collapses to the ground. The video stops.

Palden Choetso’s self-immolation was also filmed from a second story window above the street. This grainy video starts as dozens of Tibetan witnesses quickly gather around Choetso’s prostrate body, immobilized and afire, her legs and feet contorted off the ground. The crowd is several people deep. A monk inside the circle paces and pulls a large yellow cloth from a plastic package as he waits for the blaze to die back enough to permit him to draw nearer. He stands poised to cover the nun’s body with the cloth as several white khatag are thrown like streamers to the nun’s burning body. The camera angle shifts to focus on a Tibetan man with a long stick at the edge of the crowd; he is holding back half a dozen police from breaking through the Tibetan crowd towards the nun. The film stops. Two short clips of several seconds each show Palden Choetso’s black, burned corpse surrounded by shiny white khatag in a monastery; one video zooms in on small damaged photos of the Dalai Lama and another lama next to her body. One presumes she carried these images on her person that morning. Other clips show thousands of Tibetans at night, queuing with khatag and butter lamps to pay their respects, chanting prayers, and crying in a crowded temple hall. These videos of Palden Cheotso tell an unimaginable story and yet total only five minutes. A still shot from the first video, of Choetso still alive and engulfed in flame, has been used to illustrate numerous articles in the Western press, and the footage has been sequenced with others in videos by Tibetan editors for documentaries, that circulate online and elsewhere.[4]

Video and photography also show intimidating displays of force by the Chinese state by highlighting the deployments of paramilitary troops and attacks on non-violent protestors.[5] Photographs of bullet wounds, allegedly sustained when paramilitary fired into crowds, seem to have carefully omitted faces from the frame of the picture to protect the anonymity of the injured and to protect those caring for them not in hospitals but in private homes.[6]

Witnesses have been compelled to photograph the injured and charred bodies of deceased Tibetans in monasteries and private homes, including that of the beloved religious leader Sopa Rinpoche (Sonam Wangyal) and the nun Tenzin Wangmo, her blackened body smoking on an open field of green grass as a small group of maroon robed nuns run towards their sister. These constitute important visual documentary evidence of these cases and are available on websites behind warnings stating viewer discretion is advised, but such images are not typically shown in western or Tibetan media. They are both more gruesome and less dynamic in their visual power and may contravene respect for the deceased and the focus of attention on their act rather than their fate.

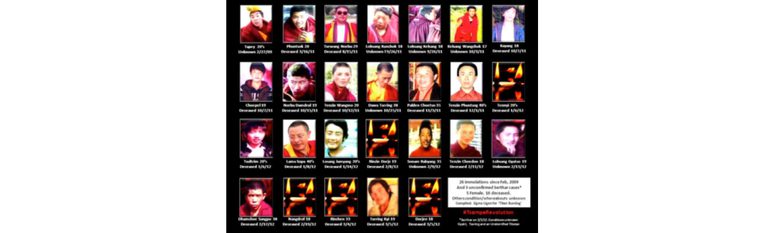

Tibetan activists worldwide instead circulate images of self-immolations and ordinary portrait pictures of the self-immolators prior to injury or death in composite images online—in blogs, Facebook and YouTube posts—and in the hands of, and even reenacted by,[9] marching and mourning Tibetans from India to Washington D.C. For example, commemorative videos feature slideshows of the self-immolators with audio tracks including Tibetan nationalistic and rock songs, a speech by the Prime Minister, Dr. Lobsang Sangay, and the tape-recorded last testament of Sopa Rinpoche. Portraits are incorporated into digital templates and used singly or chronologically arranged into one large grid, with multi-lingual captions [10] and headlines such as Freedom Hero or Patriotic Hero.[11] Arguably, exile groups hope to stir but also reach beyond their own communities with an appeal for political aid.

In recent months, I have watched these images in multiple locations and replayed them in my mind, again and again. I have struggled with a tension between the specificity of one life and collective concerns and responses that life is said to represent. The available images make the individual real to us, but also leave me craving fuller knowledge of the unique circumstances (devout monastic, widowed mother, impoverished nomad) and dramatic appeals (entreating embrace of culture, plea for the return of the Dalai Lama, demand for freedom of speech and religion, for independence) each embody. Tibetan communities honor individuals, even as they become one in a growing number, when each act is depicted, each life lost is visibly grieved,[12] and distress erupts when an exact and accurate count of self-immolators is muddled.[13]

And yet, the urgency and alarm has also led to a cultural ethos in Tibet and in exile which emphasizes unity. The acts of individuals are translated into a mass movement, and central to this mobilization is the viral circulation of images. The imagery that began as slim evidence of an individual, through its circulation, becomes a symbol for global, anti-China protest.

What might these images and their varied uses tell us about the situation inside Tibet? How do we think through the ethics and politics of the circulation and viewing of human bodies on fire, burnt, beaten, or shot? I am reminded of Susan Sontag’s reflections on regarding the pain of others and her conviction that we cannot know what it is like to be there, to be them, unless we have lived it ourselves.[14] Short of this, we have only a moral imperative to not become numb to the suffering around us. We want images to do something, but, as in this long decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, images of horror can incite further violence, or become routine, even boring. Images alone, Sontag argues, do not guarantee action, especially of the sort Tibetans worldwide cannot help but place their hopes in. The afterlife of images of Tibetans’ self-immolation circulate in the faith that viewers will demand and create action. To do otherwise would foreclose the possibility of the cessation of suffering in Tibet.

28 March 2012

[1] Roger Baker, cited in Ide, William. Social Justice Fuels Self-Immolation Protests. February 8, 2012. (accessed 20 February 2012).

[2] As of 28 March 2012, there have been thirty-one confirmed cases of self-immolation inside Tibet and three by Tibetans in India. For most recent incidents in Tibet and India, see http://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/burn-03282012142200.html; for updated Fact Sheet, see http://www.savetibet.org/resource-center/maps-data-fact-sheets/self-immolation-fact-sheet

[3] Tibetan communities worldwide declined to celebrate Losar, Tibetan New Year, which began on February 22, 2012. Video and/or photography footage of seven cases of self-immolation inside Tibet, either of the act in progress and/or the condition of the body immediately afterwards, were accessible online as early as March 2012: Lobsang Phuntsok, twenty-one years old, self-immolated on 16 March 2011; Tsewang Norbu, twenty-nine years old, self-immolated on 15 August 2011; Lobsang Kunchok, eighteen years old, self-immolated 26 September 2011; Tenzin Wangmo, twenty years old, self-immolated on 17 October 2011; Dawa Tsering, thirty-eight years old, self-immolated on 25 October 2011; Palden Choesang (Choetso), thirty-five years old, self-immolated on 3 November 2011; Sonam Wangyal, Sopa Rinpoche, forty-two years old, self-immolated on 8 January 2012.

[4] For example, see the Tibetan Youth Congress of Dharamsala video “Tibetans self-immolation inside Tibet,” Edited by Tenzin Norsang Panamserkhang, 26 February 2012.

[5] Photographs of abuse and injury, see Woeser, Sherab. Gory Images of Tibetans killed and injured reach exile. 2 February 2012. (accessed 21 February 2012).Video showing security deployments include: Watts, Jonathan and Ken Macfarlane. Inside Tibet's heart of protest-video. 10 February 2012. (accessed 21 February 2012).

[6] http://www.freetibet.org/campaigns/photos. The cropping may have been done prior to publication, but editorial intervention is frequently seen as blurred out faces.

[7] http://tibet.net/2012/02/04/serta-crackdown-photos/sarta-dawa-_19_/

[8] http://tibet.net/2012/01/31/chinese-crackdown-on-tibetan-region-nears-breaking-point/tibet-3/

[9] At a Washington, D.C. rally, during the recitation of the names of the self-immolators, lay and monastic Tibetans burst one by one from a circle of observers holding protest and memorial images. They twirled red- orange cloth around their bodies before pulling it over their heads and falling to the ground. See 9:40 minutes into the video “Tibet is Burning” by Lhaksam Media.

[10] The commemorative images are labeled in combinations of English, Tibetan, and Chinese, with information regarding individuals’ name, age, date of self-immolation, monastery or town of origin, and status as deceased, critical condition, or missing.

[11] The use of Freedom Hero, also translatable as Independence Hero [rang btsan dpa’ bo pa], and Patriotic Hero [rgyal gces dpa’ bo] could be analyzed in light of the rift in Tibetan exile communities regarding the nature of their political fight for either independence or autonomy and whether activism should proceed in accord with the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way approach or not. It is difficult on the basis of the scarce evidence in raw footage to deduce the self-immolators’ intentions, feelings, and hopes; the ways in which others frame their images and actions can make discernment of individual Tibetans’ acts even more challenging but illumine the concerns of various collectives.

[12] Yangsi Rinpoche, President of Maitripa College in Portland, OR, said the reaction of the Tibetan community is mainly sadness over “the loss of even one Tibetan life.” Additionally, the urge arises to “protect non-violence” such that these incidents do not “jeopardize the benefit in the world and for Tibet” that has so far been attained through non-violence, and finally, the fear that this act may spread into Tibetan communities outside Tibet, such as in India and the West, which would be also “very sad”. Personal Communication, 2 March 2012.

[13] For example, Woeser has written passionate condemnations of the Prime Minister of the Central Tibetan Authority in exile, Dr. Lobsang Sangay’s, omission from a recitation of names of Tapey, the first monk to self-immolate in 2009, and on various blogs and comment sections in online news sites, Tibetans have objected to terms such as “more than two dozen” in favor of an exact number.

[14] Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.