The Ambivalence of Martyrs and the Counter-revolution

From the Series: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Egypt a Year after January 25th

From the Series: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Egypt a Year after January 25th

Abridged version from the AAA panel, “Revolution in the Middle East and North Africa: Anthropological Perspectives”

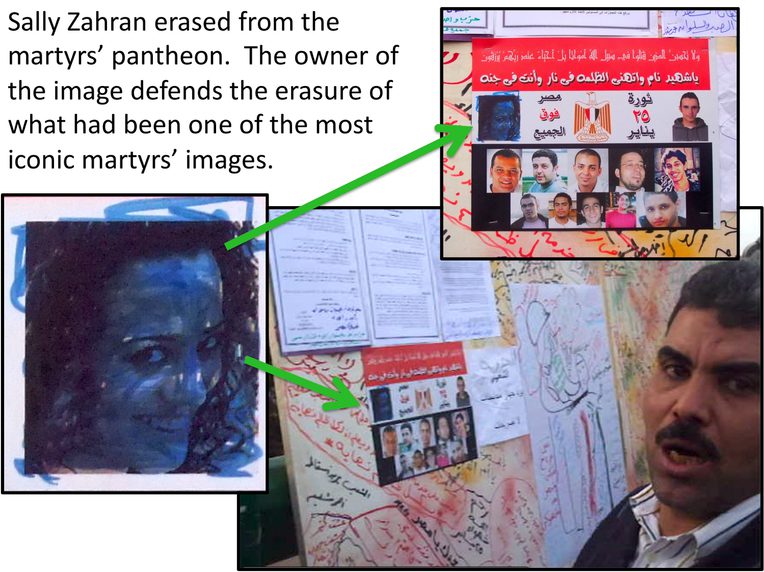

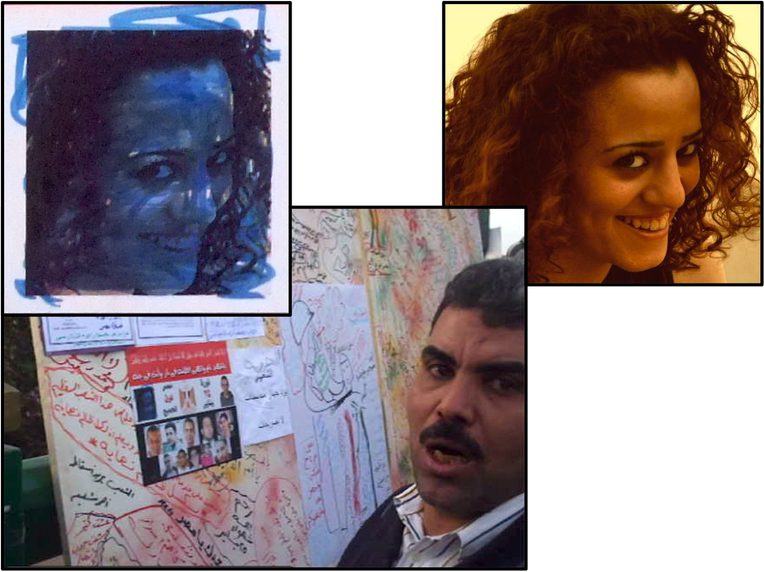

For me the story of Sally Zahran began in Midan al-Tahrir on Friday February 25th. At one point I was standing in front of a “newspaper wall” on which manifestos, artwork and graffiti were posted. Suddenly the voice of a man behind me rose angrily: “Look what the Muslim Brothers have done! Those sons of dogs – they’ve wiped out her picture just because she isn’t wearing a higab.” I had no idea what they were talking about. Then I noticed which bit of paper on the wall they were referring to: a poster commemorating some of those killed by the Mubarak regime. The reason this poster caused outrage was that one of the twelve faces had been scribbled out by a blue felt-tipped pen: it was the female martyr on the poster: Sally Zahran.

Martyr posters were ubiquitous by then. But this otherwise common poster had a guardian, as if the person or group who posted it expected trouble. He was a middle-aged man with just a small hint on his forehead of a zabiba (a “prayer mark” cultivated by many pious men). The guardian of the defaced poster mumbled to the two angry men that Zahran had been a Muslim woman who wore the Islamic head-scarf, and that all the un-veiled pictures of her on the internet were being replaced by a new one of her as a muhaggaba (veiled woman). The angry men appeared disgusted, but not enough to start a fight. They moved on, leaving the defender of the disfigured martyr poster to carry on with his mission.

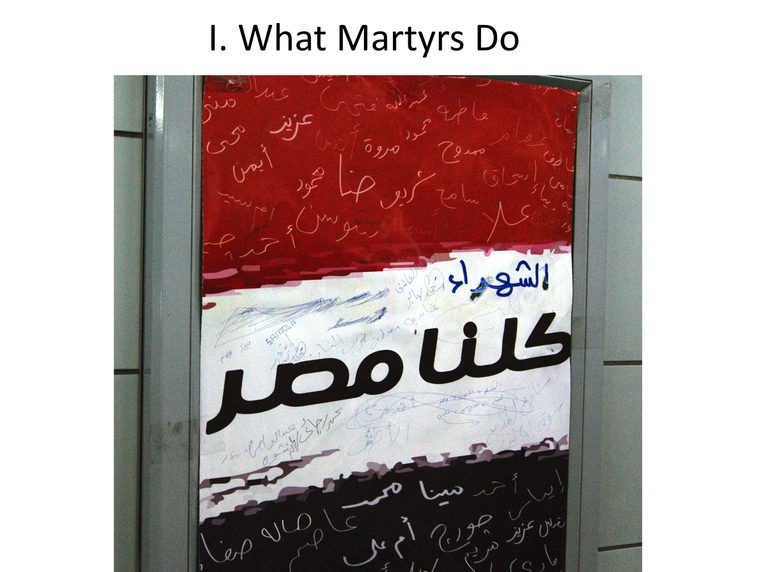

In the months after Mubarak’s abdication no complex of symbols and images was as effective as a vehicle for trying to express Revolutionary meaning as that of martyrdom. Martyr images projected into discourse or public space implicitly demanded that anyone viewing them declare a position on what they signified. This is nowhere more clear than in the brief history of Sally Zahran.

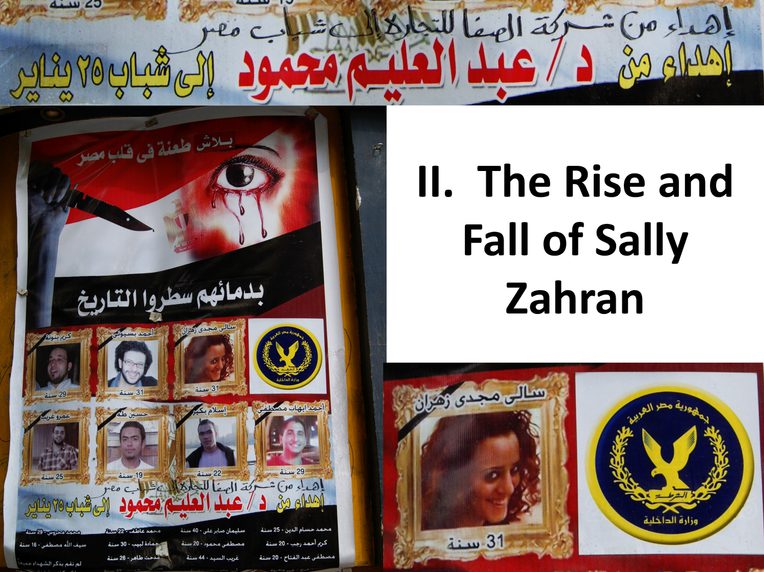

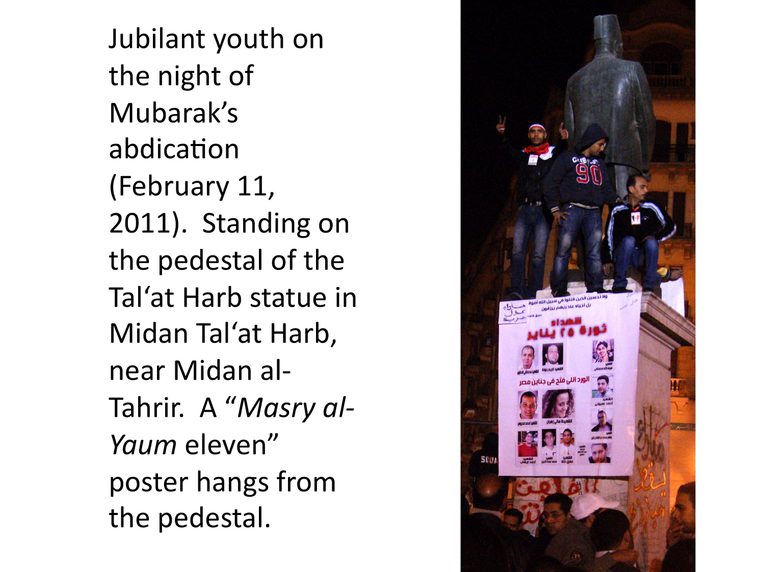

By the time I really noticed her, the unveiled Zahran had appeared on countless posters, making her very famous. The “Ur-text” of January 25th martyrology was a full-page feature of eleven martyr faces published in the newspaper al-Masry al-Yaum on February 6th.

Sally Zahran was the largest, most central, and the most eye-catching face on the page, and she was the only woman.

This image was instantly adopted in protests. Whether by design or by chance, the eleven Masry al-Yaum martyrs became the basis of revolutionary paraphernalia sold in and around Tahrir Square.

The same faces dominate representations of martyrs in other media, such as commercial video clips, displays in shops and car windows, cardboard amulets and quasi-official looking “revolution badges,” as well as posters in the streets and on buildings. There are many variations and elaborations on the martyr theme, but long after the fall of the regime remarkably few commercial or memorialist assemblages of martyrs’ faces have been completely devoid of the original newspaper martyrs’ images.

By the time I almost landed in the middle of a fight over Sally Zahran’s image on February 25th, controversy over her martyr narrative had been percolating for a while. It was known that she was a 23 year-old activist, though not of long standing. All accounts of her death agree that she died on January 28th — the “Friday of Rage” that left the Central Security Forces broken after four straight days of trying to suppress demonstrations.

Al-Masry al-Yaum’s famous martyrs’ feature carried the caption “She was on her way to Tahrir Square when she was stopped by thugs, and hit on the head by a club. She died from the effects of a brain hemorrhage.” This version of Zahran’s story went “viral,” elevating her not just to fame in Egypt, but to global status within a few days.

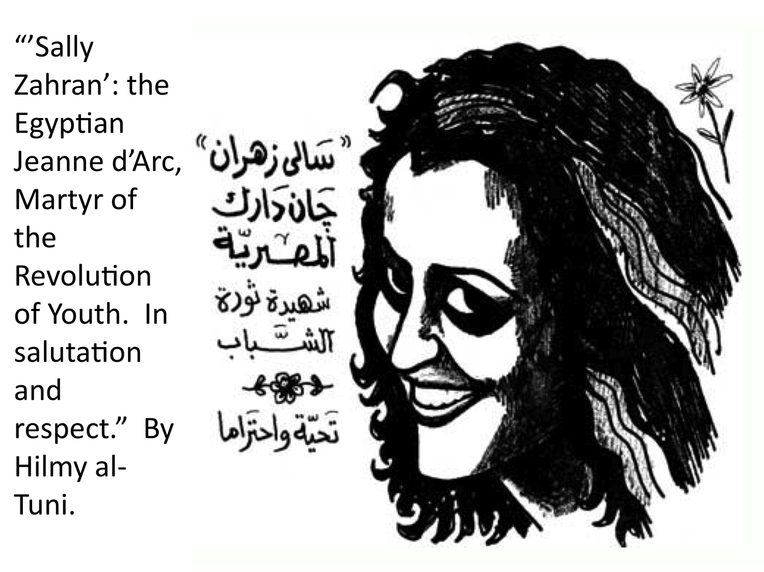

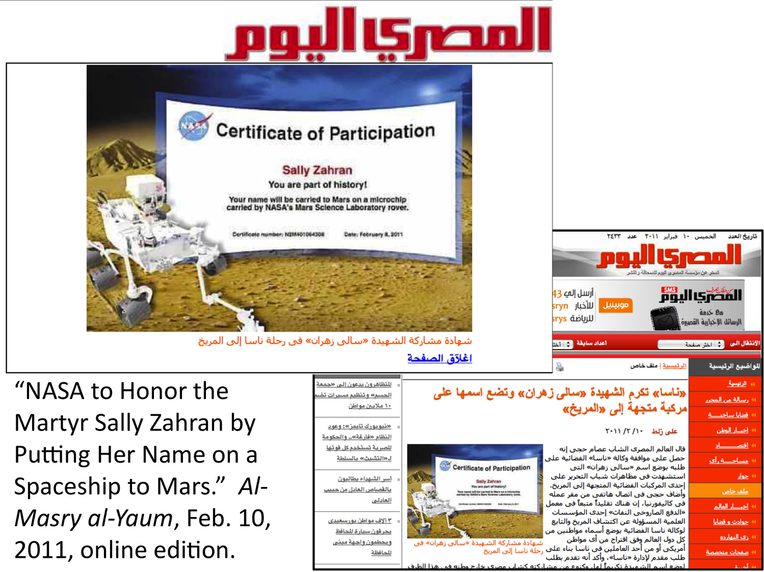

A prominent artist painted her image, anointing Zahran the “Egyptian Jeanne d’Arc” — a phrase and image repeated on countless blogs and forums. Star actor Ahmad Hilmy was supposedly planning a film on the Revolution in which his wife, an equally famous actress, would play Zahran. A report in al-Masry al-Yaum claimed that an Egyptian employee of NASA had requested that her name be inscribed on a microchip placed on a future mission to Mars. This mutated into reports copied all over the internet that NASA would actually name the spaceship itself in her honor.

Just as Zahran’s martyrdom went global, the contours of her story began to change in Egypt. Al-Masry al-Yaum reported that Zahran had actually not been in Cairo on January 28th. She was instead in the Upper Egyptian town of Sohag, where her parents lived. Shortly thereafter additional details emerged that conflicted with the iconic image of Zahran slain in battle.

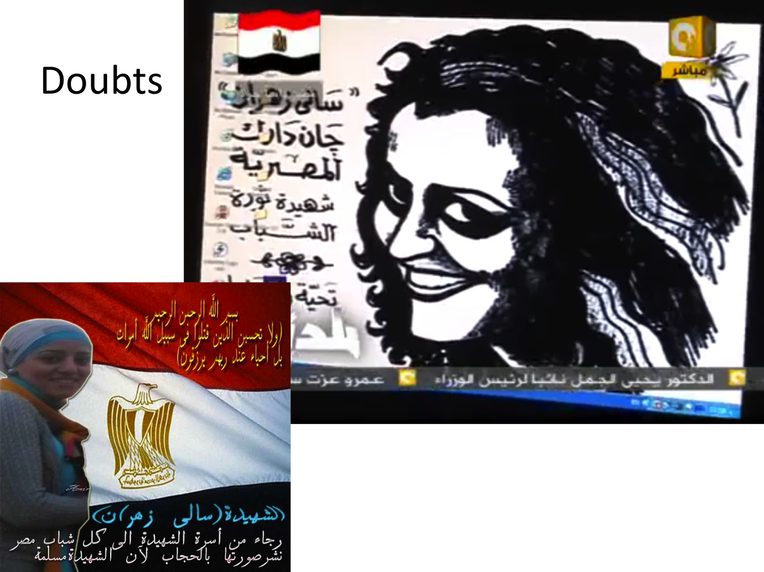

Zahran was not in fact veiled. Her brother said as much in the press, and two people I spoke to who knew her confirmed this. Nonetheless the claim that Zahran was veiled and that her family was pained by her un-higabbed image quickly attained the status of fact for many. Postings of the unveiled Zahran were met with snippy messages asking to have it removed. In some cases a picture of a veiled Zahran was superimposed onto the original photo.

But controversies over Zahran’s status as a muhaggaba were further complicated by new twists to the story. On February 24th a popular talk show broadcast an interview with Zahran’s family, in which they suggested that she had not died from being clubbed on the head by regime thugs. Rather she had been trying to leave home to join the demonstrations against her mother’s wishes and had either jumped or fallen from the family’s 9th floor balcony while trying to leave the house.

For many, the television interview was the definitive word on how Zahran died. A few believed that her family was compelled by forces sympathetic to the old regime to issue a denial of the heroic martyr story, under threats that something would happen to her brothers if they didn’t. The interview undeniably poured oil on the fires of debate over the meaning of Sally Zahran’s martyrdom, and for some, whether she should even be considered a martyr. From the very beginning people opposed to the revolution claimed that the martyr stories were fabricated. A low-level NDP official I met at a Revolution-themed cultural event scoffed at the martyr stories, and said “how many really died? Four? Five?” So the discrediting of Zahran certainly played a role in anti-revolution propaganda.

Debates intensified over the significance of Zahran’s higab or lack thereof. Her mother authored the requests forwarded to Facebook that her daughter’s un-higabed pictures be struck from the public record — or at least this is what those wanting her to be shown veiled believed. But throughout the television interview in her own home Zahran’s mother sat surrounded by precisely the iconic images of the un-higabed Sally that had become so familiar to the world. The confusing stories of her family wanting her to be known as a muhaggaba, and then appearing on television amid pictures of her without a higab, fueled disagreements between the liberals and the Islamists.

Elsewhere I have discussed the “afterlife” of Sally Zahran in various contexts. The central point is that as a means for bringing this wide range of submerged tensions into the open, Sally Zahran was more productive than any other martyr because she highlighted social tensions. She functioned as a prism refracting the light of events; a kind of medium, in other words, that redirects meanings. The Revolution was not about women, but it propelled initiatives to re-think the place of women in society. It was not about religion, but it opened a Pandora’s box of religious problems that the Mubarak regime had deliberately incubated. In the early days of the Revolution, martyrdom was an actively performed rhetorical position — a kind of irresistible force in the eyes of those who took it up as a weapon in their continuing struggle. Sally Zahran, a “flawed” martyr, demonstrates how martyrs move people to action better than the presumably more normative cases that stand a better chance of permanent memorialization. Martyrs did not in fact constitute an irresistible force in the Revolution. A variety of immovable objects always countered them, ranging from the intransigence of the ruling Military Council to patriotism, which is perhaps the most massive of all immovable objects. The regime and its sympathizers started generating a fog of patriotism long before Mubarak left office, and it provided ample hiding space for anyone who feared close scrutiny in the post-regime environment. The martyr inconveniently asks, “who killed me?” And true revolutionaries take up the cause, also asking, “who killed them,” in the hope that they can beat the false patriots out of the fog. It’s hard to know whether or not they can succeed. The fog gets thicker and thicker. The Revolution hasn’t failed, but ambitious goals, such as achieving social and economic justice, or even basic human dignity, have not yet been achieved. Sally Zahran died for those goals, and one hopes that her death will not have been in vain.