The Cost of Disruption and Aesthetic Assets

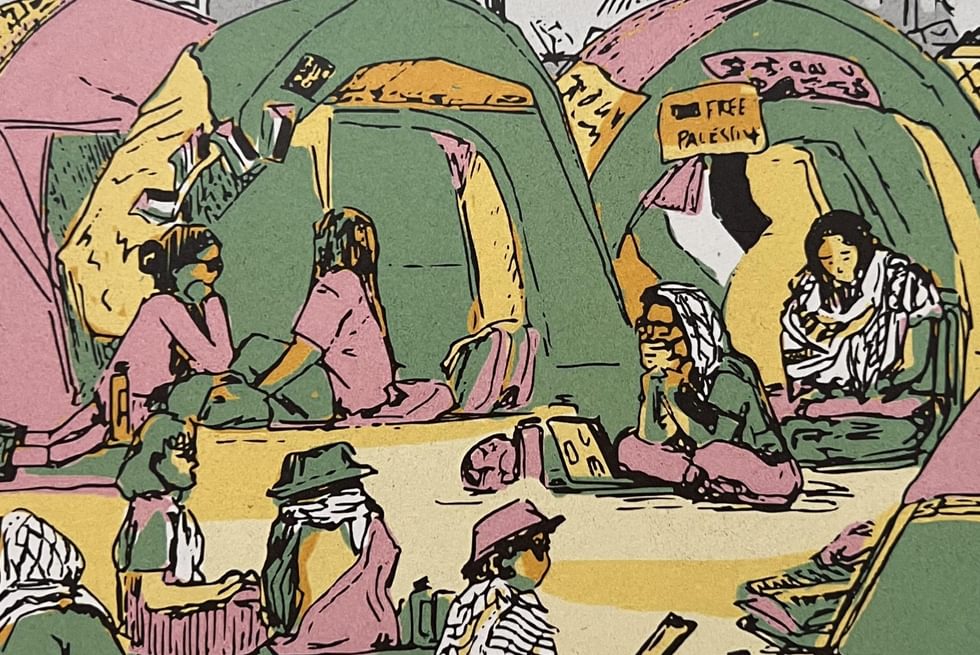

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

In 1860, a few decades after Thomas Jefferson began ordering enslaved labor to build his educational pet project atop stolen Monacan land, the first appointed groundskeeper of the university planted a ginkgo biloba tree on the northwest side of the Rotunda just adjacent to the University of Virginia’s historic Lawn. In April 2024, a community protesting UVA’s endowment investments in companies benefiting from the genocide in Gaza encamped under its wide and generous shade and set up a space where we fed each other, prayed, locked arms, sang, and screamed truth to power.

The gingko, native to East Asia, has shown resistance to biological aging and its leaves have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for centuries to combat illnesses like dementia and other conditions. Genetically the oldest tree in the world, this particular ginkgo biloba has been living on Monocan land for 164 years, which earns it the title of being a “witness tree”: the gingko biloba is a witness that promises to remember.

On the morning of May 4, 2024, UVA administrators called in hundreds of state and local police officers clad in riot gear, several holding semiautomatic weapons and grenade launchers, to clear our solidarity encampment repeating tactics from previous weeks at other public universities in Virginia such as Virginia Commonwealth University and Virginia Tech to break up pro-Palestinian protest. In the hours that followed, officers wantonly released chemical agents, pushed the crowd into oncoming traffic, threw protesters to the ground, and dragged arrestees across UVA’s Lawn.

In contrast, on August 11, 2017, UVA administrators instructed their officers to stand down as a group of torch-wielding white supremacists chanting “blood and soil” and “Jews will not replace us” attacked anti-racist counter-protesters gathered at the statue of Thomas Jefferson outside the university’s Rotunda.

What are we to make of this contrast: on the one hand, limited police interference in the face of white supremacist violence and, on the other, the full force of a militarized state unleashed on a small crowd of students, faculty, staff, and Charlottesville community members calling for UVA to divestment from genocide and war profiteering on Palestinian land and people?

In the wake of police and far-right violence at university encampments, we argue that the pro-Palestinian protesters’ non-violence does not help us rationalize or argue against the repression faced by protesters. Rather, we hope to show that the visibility of colonized people, both in rhetoric about the Palestinian people as well as the presence of Palestinian, Black, Latinx, Pilipinx, and other protesters with roots in colonized land demanding an end to colonial oppression, represented a real threat to UVA’s financial and historical brand. For this reason, UVA administrators felt obligated to legitimize extreme forms of violence and brutality against a group that included the very students they had pledged to protect.

Racial and colonial violence was always present and active at UVA, through their long-held investments in apartheid and other neocolonial regimes. The encampment on the historic UVA lawn is what made that violence visible, both in our presence in demanding disclosure and divestment, and in the subsequent repression that the administration inflicted to evict us.

For much of UVA’s early history, violence against enslaved laborers, by design, was pervasive and routine, but hidden from view. In their work Educated in Tyranny, architectural historians Louis P. Nelson and Maurie D. McInnis describe the dual landscape of university grounds, also known as the Academical Village. The bricks of the Academical Village, which centers the historic Lawn, were paid for and laid by Black enslaved labor. This violence was never absolved and remains calcified in the preserved space of the Lawn, which Nelson and McInnis dub a “landscape of slavery” at the core of the university.

For instance, university investment in arms manufacturers, and the many other institutions that contribute to the ongoing genocide in Gaza, demonstrates how peaceful, pristine, quiet spaces in the Global North like UVA are directly reliant on the chaos and violence inflicted on colonized people and their land. UVA develops military technology by recruiting knowledge workers to do so and benefits financially from colonial wars like that in Palestine, but maintains the Lawn as an aesthetically peaceful space.

This tradition remained alive during my time (Cady) at UVA. In 2020, the year I arrived in Charlottesville, Hira Azher, a Muslim student experiencing disability while living in a room on the historic Lawn covered her door with a protest sign that read “FUCK UVA. UVA OPERATING COST: KKKOPS, GENOCIDE, SLAVERY, DISABILITY, AND BLACK AND BROWN LIFE.” Alumnus Bert Ellis, wrote in a Facebook group for UVA parents that he drove hours to Charlottesville with a razor blade to remove the sign himself because the university had not taken immediate action. Three years later, Ellis was appointed by Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin to the Board of Visitors, a position that has provided him local and national attention in his crusade to end DEI funding at universities and restore Jefferson’s ideals. In the fallout of the lawn sign controversy, UVA wrote a public letter asserting the university’s legal authority to remove Azher’s statement. In it, then-University Counsel Timothy J. Heaphy wrote, “the speech may clash with the beauty of the lawn […but] its regulation would be content-based and unconstitutional.” Though arguing that Azher’s constitutional rights ultimately were protected, Heaphy’s focus on aesthetics is revealing. Rather than appeal to justice or the content of the critique, instead, Heaphy positions the Lawn as a pastoral and apolitical zone under threat from student testimonies that speak to the status-quo violence at UVA.

By the time I (Cady) was selected to receive a Lawn room a few years later (a recognition of community leadership within the UVA ecosystem), administrators had written a policy to only allow messages that fit on 11x16 inch plaques. To the administration, Azher’s sign was perceived as disruptive enough to the aesthetic space of the historic Lawn to justify a restriction on speech. In making the violent oppression that the space represents apparent to the viewer, Azher’s sign validated BIPOC students’ experiences and felt like a breath of air after being choked by the delusional idyllic reputation UVA puts out.

After living on the Lawn for an entire academic year, sleeping on the ground under the gingko tree in the encampment was the first time I felt peace in that location. Participants shared a space where needs were met, with donations of food and medicine from the community, and where we spent many hours sharing stories about the ground we occupied and imagined how we could build our community in service to collective liberation from Palestine to Charlottesville. The university’s need to banish protest, or disruptions, from their pretty pristine picture, is a way to obfuscate the truth. But this aesthetic manicuring is more than ideologically important to UVA’s interests.

Over the past decades, universities (including UVA) have sought to diversify their revenue streams in the face of limited state support and the idea that tuition prices can no longer be used reliably to cover budgetary shortfalls. In addition to finding new revenue-generating opportunities to continue to compete in the “college amenities arms race,” universities often borrow money to fund their construction and renovation projects, a process that requires that they demonstrate to federal credit agencies that they can reliably pay back what they have borrowed. And, indeed, UVA has a AAA credit rating from Standard and Poor’s, a rating higher than that of the federal government, a designation UVA has touted to explain to potential investors why it is a safe and smart place for the well-heeled to park their cash.

Both of these strategies–diversification of revenue streams through university programs and the ability to borrow money at favorable rates–rely on reputation and the ability to downgrade risk, financial and physical among them. UVA’s bond prospectuses combine these two pressures, boasting about the university’s physical and historic infrastructure as much as they do its academic prestige.

For instance, in a $100 million bond prospectus from 2021 for debt purchased by Goldman Sachs, UVA administrators detail their academic rankings, the number of Rhodes Scholars they have produced, and what they see as markers of “a student experience without parallel in higher education” (A-1). Notably, the bond prospectus’ authors tie their virtues to UVA’s heritage, namely that of Thomas Jefferson. In terms of infrastructure, they explain that the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) named the Academical Village a World Heritage Site—the only operating university in the world to hold this designation—in 1987. This status was received just months after student protesters won their case against the university in a United States District Court to protect their ability to erect shantytowns protesting the University’s investments in South African apartheid, which the university argued were simply “unattractive.”

This idea that protest is ugly and thus detracts from the aesthetic vision the university presents of itself is a structuring logic for the bond prospectus. Violence appears only elliptically in the narrative, first when discussing the newly-erected Memorial to Enslaved Laborers in only a single sentence and without mentioning UVA’s history of slavery. Further, despite being released in the years after the events of August 11 and 12, 2017, made international headlines and catalyzed a flurry of academic investments and institutes in democracy at UVA, these recent events, ones that surely threaten the university’s reputation, are also not mentioned. Instead, Heaphy appears again but only for having conducted an independent review that led to “new policies on public protest.” The prospectus fails to make explicit the fact that Heaphy wrote his report in response to racial violence on UVA’s campus, nor to even give the date, instead leaving the details to the readers’ imaginations. Further, the solution to white supremacist threats, the document alleges, are better policies, a rhetorical strategy akin to the Lawn’s aesthetic construction: if you cannot see it, it is almost as though it is not there.

Such descriptions serve as the backstory to UVA’s detailed enumeration of its financial status and, importantly for investors, its ability to ensure that the fund of money to Wall Street will continue unabated. Given the interconnected nature of this narrative, any action that ruptures the carefully constructed image of UVA as a beautiful, physically placid landscape also threatens its bottom line. Students and community members putting their bodies at risk to highlight the harm UVA did to Palestinians suffering in Gaza and the West Bank was just such a rupture.

We return now to the question with which we began: why violently punish anti-imperialist student activists calling for divestment from Israeli apartheid and the genocide of Palestinian people, an action that realizes the very ethics UVA claims to inculcate? One answer lies in our contention that UVA’s construction of physical safety in its infrastructure depends upon routine colonial violence, so long as that violence can be hidden from view.

In contrast, UVA’s Liberated Zone for Gaza created a radically different order of life in the University’s historic center, a hyper-visible disruption of the status quo and of the story the university sold to its stakeholders. When university administrators chose to respond to that demonstration with extreme violence, they illustrated a core truth: that a collective of students, many whom are people of color intimate with colonial violence, advocating for liberation for a colonized people suffering genocide, threatened UVA’s historic and financial investment in an aestheticized vision of peace.