This post builds on the research article “The Cross Politics of Ecuador's Penal State,” which was published in the August 2010 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Interview with the Author

This Fall, Chris Garces, author of "The Cross Politics of Ecuador's Penal State," agreed to answer a few questions from CA intern Robert Samet. What follows are Garces' thoughts on sacrifice, prison reform in Guayaquil under President Rafael Correa, and the overall trajectory of his research in Ecuador.

Chris Garces taught for three years at Sarah Lawrence College before moving to Cornell, where he holds a Mellon-funded postdoctoral fellowship and a visiting assistant professorship. His dissertation, “Whither Charity? Andean Catholic Politics & the Secularization of Sacrifice,” tracks how Catholic charities in Ecuador haltingly incorporated expert medical and labor knowledges into their traditional injunction to care for the poor, telling hidden stories about the non-secular origins of the modern Ecuadorian state. His writings have appeared in Anthropological Quarterly, Anthropology & Humanism, Hispanic American Historical Review, Material Religion, Íconos: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, and the encyclopedia Iberia and the Americas, among other places. He is currently preparing a book-length manuscript on early colonial race relations in Peru and their representations across Catholic hagiographic and viceroyal administrative literatures.

Robert Samet is a doctoral student in cultural anthropology at Stanford University. His dissertation, "Deadline: The Popular Politics of Crime Journalism in Caracas, Venezuela," looks at how representations of violence are reproduced and mobilized within a larger discourse of "security." He has been an editorial intern for CA since 2009.

Hello Chris. Thanks for agreeing to take a few questions for our readers.

My pleasure.

Perhaps you could start off by explaining how you came to the topic of the prison protests and how they fit within the larger scope of your research?

My prison fieldwork was part of a two-year research project in Guayaquil, Ecuador, studying predominant forms of Catholic humanitarianism and their shifting relationship to the discourse of state across the nation’s postcolonial era. Specifically, I trained my historical and ethnographic research on the slow, uneven incorporation of expert biomedical and labor knowledge within the traditional Catholic injunction to care for the poor. This project demanded empirically grounding and interrogating the classic anthropological claim that gift-giving is a form of sacrifice, and sacrifice a rather peculiar, supernatural variant on gift exchange. Ultimately, my archive and field work on Catholic humanitarianism traced an unfamiliar genealogy of the standard-normative historiographical argument among Ecuadorianists that the country’s 1830 Independence, along with its 1895 Liberal Revolution, sacrificed indigenous interests and revitalized Creole agro-capitalist political hegemony: illuminating the intensified yet increasingly covert applications of charity as a modern political instrument.

What I discovered, in other words, was that a long-forgotten scholastic and Catholic virtuous ideal (Heyd 2009) – which I call “saintly ethics” (Garces 2007), or self-sacrificial acts that are “good to do, but not bad not to do” – had quietly become intrinsic to modern Ecuadorian political subjectivities while defying the ideological left and right-wing polarization of today’s Latin American Church: no matter their proper name, Ecuadorian charities signal a zone of great politico-theological influence and an implacable formation of “valorous” yet iniquitous gift-giving relationships on the ground. The anthropological study of charity is never just about the measure of good acts. The charitable impulse and its sacrificial entanglements, perforce, were the guiding epistemological juncture of my investigation, so when the preventively imprisoned housed inside the Penitenciaría del Litoral began their Christian spectacle, my ethnographic work shifted in tandem to analyze Ecuadorian public theologies and the emerging penal state.

Throughout my time in the Peni, I investigated the protestors’ “saintly ethics,” in this case, as a mechanism of public and private contestation that afforded indefinitely detained suspects a symbolic space in which to critique their punitive containment across the neoliberalization of the city—analyzing their bloodletting “martyrdom,” or their self-sacrificial gesture, and how their public crucifixions turned into an “organizing principle for [a] politico-theological [movement]… and a way of being in the world that unconsciously makes legible a spirit of charity beyond reproach” (p. 473).

Your essay on the prison protests in Ecuador is at the intersection of several key issues of interest to contemporary anthropology—sovereign power, neoliberalism, the penal state, sacrificial violence, and what you refer to as the “postsecular”. How do you see these things overlapping?

The ethnographies I find most meaningful cut across well-policed academic and political borders—hence Geertz’s still-resonant description (following Kluckhohn) of cultural anthropology’s boundless and shrewd hermeneutic potential as an “intellectual poaching license” (Geertz 1983: 21). I take your question as a welcome provocation to defend all the essay’s moving parts, so to speak; but as I do so, I stay wary that any such attempt to define the whole—whether as a cosmology, cultural configuration, ethnographic totality, global assemblage, political theology, or even as the intersection of key issues—only acquires critical purchase upon empirically auguring a break from standard-normative perceptions of intellectual and political order(s). It takes far more than a macro-level, qualitative insight to live up to Geertz’s challenge—demanding no less than a counter-intuitive disciplinary weltanschauung—and it would be grandiose for me to claim anything of the sort for this article.

Simply put, my research in this issue of CA problematizes a successful Ecuadorian protest inside a federal prison in which indefinitely detained suspects—thousands of individuals charged mainly with petty crimes, who remained without sentence for years—were able to spectacularly crucify themselves in order to denounce their abject legal situation and to broadcast their demands for basic civil rights and protections. The key open question raised by this work, I would suggest, is why the globally surging penal state should not be linked conceptually with the transformations of sacrificial violence, or perhaps how “neoliberalism” and “the postsecular” (a pair of keywords that each problematize international democratic capitalism, foundational structures of belief, and implicit notions of collective providence) could even plausibly be considered discrete, non-overlapping scholarly areas for investigation. I fail to see why these pairs of key terms shouldn’t be pitted against one another to interrogate how we are differently caught between past and future. Not when whole populations and stigmatized demographic groups, on a global scale, are respectively profiled, persecuted, and thrown into local prisons, or even worse, in order to justify the moral hegemony of an international majoritarian private-public “sense of security.”

From the outset of the prisoners’ campaign of crucifixions, like most Ecuadorians, I understood that all citizens were vaguely implicated by the neoliberal transformation of the prison into a space for preemptively storing away urban crime suspects. Whence the power of sacrificial imagery and its lasting reserve of political influence—a critical language that somehow manages to forge a symbolic bridge across liberal and illiberal frameworks of and for civil interests. The overall hope of my article is that, in following the prisoners’ epochal gesture, or the immediate collapse of religious and secular domains within a single “evental site” (to borrow a coinage from Badiou [2003]), I will demonstrate how the rising security state and its telescoping projections of shadowy criminal suspects might be analytically grasped and dismantled.

The wordplay of “cross politics” in my title means plenty of things. Most basically, it points to the impossibility of viewing the political as a singular zone of autonomous contestation, disarticulated from religious, jural and cross-cultural modalities of normativization. I view my work in this piece as part of a broader attempt to rehabilitate comparative preoccupations with the mediation of autonomy as well as the attempt to comprehend non-agentive influence in today’s world; specifically in keeping with the interwar Marcel Mauss, I seek to identify the fully integrative, yet dangerously mechanical, dynamics of contemporary life (Garces & Jones 2009), letting such concerns speak directly to our own academic, and rather uneasy participation in democratic processes of international capitalist self-government and endemic low intensity warfare on a global scale. The proper area of methodologically inductive anthropological research, from this perspective at least, is a critique of what all goes-without-saying varieties and zones of moral righteousness fail to consider and leave behind.

Regarding “the postsecular”… This unfortunate modifier, “post-,” appears tacitly to defend evolutionism, or to suggest the notion that world historical processes have passed through a once-superannuated and now a revitalized “religious stage,” only this time in accord with the secular-humanitarian ideals of Western democratic governments. Against this interpretive sleight of hand, which would reintroduce a clear-cut Orientalist divide of a curious postmodern stripe (see: News, Fox), I would argue instead that moving beyond any a priori understandings of the secular—especially its value as “not religious”—should be considered heuristically part and parcel with anthropology’s most challenging cross-disciplinary and anti-nationalist oppositional legacies. The use of the term postsecular in my essay reveals how religious action may serve as a political catalyst in tandem with other domains of authority, especially towards the unlikely creation of broad-based coalitions, up to and including collective mobilization against “security” as a hegemonic private-public discourse.

This argument highlights the multiple sacrificial dynamics (forms of victimhood, victim substitution, and vicarious participation in the sacrificial event) that took place across the 2003-4 crucifixion protests in Ecuador. The harnessing of sacrifice and its mass-mediation gave Ecuador’s juridical hostages, a community entirely submerged within the security state, a uniquely contingent event in which to charismatically protest the injustice of their punitive containment both inside and outside the prison. My essay as such works against the predominant exponents of postsecular critique in continental philosophy today. The very notion that a worldwide public resurgence in theology has psychoanalytically “returned” modern societies to their hidden traumatic core in narratives of religious origin (Žižek 2009), or subtly “reactivated” the evangelical promise of universalization within particular global insurgency practices (Badiou 2003) betrays a certain geographical hermeticism—a necessarily occidental perspective struggling to free itself from the web of its own, secular-liberal academic and political foundations. Anthropologists have always lived and known otherwise.

Sacrifice is the central motif of this article, and you give us a concrete understanding of how self-sacrifice taps into the politico-theological imagery of Ecuador. Could you talk more broadly about how this article speaks to the larger body of work on sacrifice as conceived by anthropologists?

Thank you. I feel as though answering your question could have served as the conclusion to my article just as long as the essay’s guiding empirical and political topics, described above, did not take precedence. My entry point into this question is via the seemingly inexhaustible resurgence of anthropological interest in the body. A great deal of ethnographic work by now has problematized the body as a site of disciplinary power and/or contestation (usually associated with the “early” Foucault), or analyzed embodied practice as a privileged location for the cultivation of virtue, ethical relations, and subjective dispositions (usually associated with the “late” Foucault). These theoretical schemata demonstrate how the culturally and historically informed body is made docile or willfully pliable across a variety of contemporary settings—whether neoliberal (for example Edmonds 2007), illiberal (for example Valiani 2010 in CA), or even counter-liberal (for example, Mahmood 2001 in CA). My research on prisoners’ spectacular contestation of Ecuadorian sovereign violence draws from each of these lines of inquiry into corporality, yet it also demonstrates, through a close ethnographic reading of the processes of “urban renewal” in Guayaquil, how sacrificial rhetoric and practices ultimately victimize the bodies of all those who find themselves caught deepest inside the burgeoning penal state complex and its secular-legal justifications.

The anthropological study of sacrifice I draw upon is already mapped out very well in Valerio Valeri’s concise, sweeping account of the literature on ritual sacrifice and the symbolic efficacy of culturally mediated political victimhood (1985: 62-70). In Valeri’s overview, “[m]ost [anthropological] theories of sacrifice are based on one of the following theses or on some combination of them[:]

1. Sacrifice is a gift to the gods and is part of a process of exchange between gods and humans

2. Sacrifice is a communion between man and god through a meal.

3. Sacrifice is an efficacious representation.

4. Sacrifice is a cathartic act.” (ibid: 62, emphasis added)

Another strand of indispensible scholarship is currently emerging from religious studies, for example in Ivan Strenski’s most recent publications (2002, 2003), suggesting how general theories of sacrifice were developed within the most thinly secularized academic traditions, i.e. disciplinary matrices with national and intellectual roots pulling deeply from world-historical events and religious counter-currents to modern state formations. To take but one example, the Année Sociologique’s rendering of religious phenomena would be unimaginable without the Dreyfus affair as immediate political background, as with the editorial group’s contestation of the rising European tide of xenophobic anti-Semitism lurking across their arguments for international solidarity and recognition-with-difference (2002). Here in my article, I draw on both the anthropology and intellectual history of sacrifice to lodge my argument. However, my particular interest derives from an ad hoc genealogy of the way early 20th century anthropologists began to comprehend sacred violence and its englobing effects by appealing to then-prominent notions of communication and sociological reproduction.

Consider Hubert and Mauss’s celebrated definition of sacrifice: “[s]acrifice is a religious act which, through the [sacrifier’s] consecration of a victim [or the host of sacred violence], modifies the condition of the moral person who accomplishes it or that of certain objects with which he is concerned [i.e. the sacrified] (1964[1898]:13).

If their particular understanding of sacrifice has had the longest critical half-life, as nearly all commentators, past and present, have acknowledged, and if Hubert and Mauss’s ideas remain predominant today, its intellectual use-value draws from its protean applications with/in 20th century theoretical turns and academic traditions. Like Saussure’s near-contemporary model of the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign, I would argue that Hubert and Mauss’s definition permitted a formalized structural language for the mediation of “sacrifier” / “sacrified,” turning sacred violence into a fundamentally communicative phenomenon based on a modality of collectively sanctioned yet arbitrary ritual force.

This observation may help to illuminate the cognitive slippage in self-consciousness that allows for the multiplication of difference within the same. While nearly everybody in the rapidly gentrifying city of Guayaquil would consider themselves victimized at one time or another (by actual crime, their own fears, the unpredictable vicissitudes of structural violence, or the generalized discomfort of sharing embattled public space), the literal and mass-mediated crucifixion/victimhood of Ecuador’s juridical hostages made their legal claims to constitutional protections de facto undeniable. The crucifying prisoners were not, in the strict sense of the term, the transformative agents of public sensibilities. Rather, the crucifixions granted these inmates a peculiar politico-theological “license” (i.e. the ability to “act with abandon”) to the extent that multiple publics immediately experienced co-recognition with the prisoner’s extralegal plight and misfortune. Untold numbers of Ecuadorians hence vicariously took part in the crucifixion protests—either directly (as in the collaborations of the guards, the foreign nationals, and the prison mafia) or indirectly (the rest of Ecuador’s multiple publics). But all these forms of participation were realizable only because of the peculiar character of a violent, collective sacrificial event to trans-temporally breach and transform categories of self-differentiation. This aspect of my research tacitly builds on Levy-Bruhl’s interwar investigations of the so-called “mystical,” psycho-physiological collapse of the categories of the individual and the collective, especially when a loose-knit assembly joins together to “participate” in a vitally transformative ritual observance (2010).

This anthropological framework additionally permits a thought experiment on the limits of sacrificial critique.

That is, my article works both within and against the implicit structural-communicative bias in the anthropological study of sacrifice, as well as the latent juridical unitary understanding of sacrifice (i.e. one victim, one perpetrator, one facilitator, and one single source or object for sacred violence) associated so closely with Abrahamic interpretive traditions and so problematically commonplace to standard-normative “Westernist” and “anti-Orientalist” political theologies of victimhood alike. To the contrary, I sought to show in this article how multiple forms of sacrificial identification and transformation interlace to comprise the same discursive field within the state. Allow me to elaborate.

Consider the following processes that were taking place in Guayaquil in 2003-4 as described in my article: (1) the political cleansing of the urban sphere, sponsored in large part by the conservative Social Christian Party and glossed as a providential restoration of civic “pride” through the elimination of urban pariahs; (2) the juridical, familial, and neighborhood-level abandonment of the preventively imprisoned as “unsalvageable” moral subjects; (3) the economic disenfranchisement and racialization of the city’s ethnic working classes, especially its unemployed youth now viewed as potential “anti-social” elements in Guayaquil’s emerging neoliberal order; (4) the prisoners’ use of crucifixion imagery and practice to challenge majoritarian Christian ideologies of “martyrdom,” “saintliness,” and/or worthiness for moral “recognition;” and (5) the prison guards’ collaborative identification with prisoners who denounce their status as juridical hostages, publicly revealing their own victimhood in order to alleviate dangerous prison overcrowding and mafias run amuck. As one can easily see, different groups within and outside the Pentienciaría appealed to sacrificial discourse in order to mark themselves as participants unjustly victimized by the neoliberal discursive expansion of urban crime and its punishment. My empirical question in this article was simple: how, and under what conditions, did these various domains of sacrificial discourse fold into one another?

What occurs when sacrificial domains overlap is a transfiguration of sacrificial violence itself. Using Hubert and Mauss’s classic terminology, the figure of the “sacrificer” is s/he who facilitates the mytho-symbolic ritual annihilation of the host of sacred violence; in other words, the sacrificer is a key figure in any sacrifice precisely insofar as s/he actively mediates the relation of vital destruction between sacrifier and sacrified). My article, however, presents a strange variation on the so-called “sacrificer.” The prison guards, for example, performed this ritual duty across the inmates’ 2003-4 campaign of crucifixions by looking the other way, facilitating these events entirely by omission. As I discovered through months of ethnography on the inside, the guards collaborated in part because they too were each trapped inside the prison, albeit in a different way—while criminal suspects were politico-juridically incarcerated, the guards were instead socio-economically imprisoned. The guards, vastly outnumbered by prisoners on the inside, were subject to extraordinary dangers administering the inmate population at large, and were viewed with suspicion, distrust, or worse, by potential employers on the outside (making their lateral movement to another job nearly impossible). Whatever their motivations, the guards’ collaboration with the preventively imprisoned worked towards the alleviation of prison overcrowding and the extreme dangers associated therewith. The guards were therefore partial sacrificers and partial victims in each of the prison crucifixion event(s) described. My article opens up an ethnographic space in which to analyze multiple zones of Christian sacrificial discourse and their interlacing through the “license” of a powerful, trans-temporal sacrificial event—as well as the non-recognition of subjects, such as the guards, victimized by the narrowing of “unitary” sacrificial discourse within the neoliberal democratic justification of and for an expanded penal state.

This essay situates preventative incarceration in the context of neoliberalism circa 2003-2004. Just a few years later in 2006, Rafael Correa campaigned for and won the presidency of Ecuador on a platform that rejected neoliberalism and promoted the adoption of alternative political-economic models. Have there been any changes in the penal state or in the practice of preventative incarceration under President Correa? If not, how do we explain the continuation of these practices under an administration that is, ostensibly, opposed to neoliberalism?

In a word, political transitions and events in Ecuador over the last five years show how the crucible of the emerging penal state has managed to remain largely intact in spite of Rafael Correa’s efforts to reduce prison overcrowding and the neoliberal engine of punitive containment.The prison is one of the key sites of social, economic, and political transformation brought to the fore under Correa’s administration. Clearly as you mention, I focus in this CA article on a single moment of Ecuadorian penal state development, when preventive imprisonment was left unchecked, and then successfully, if only momentarily upturned through religious protest. The juridical figure of detencion en firme (i.e. preventive imprisonment) which lay at the heart of these protests was promoted by the supporters of neoliberal reform in Ecuador, namely the Social Christian Party (PSC), along with its urban elite and business-class alliance, through a network of civic-managerial NGO Foundations that organized municipal police and security forces to ratchet up the cumulative level of surveillance on the streets of major cities. The PSC’s congressional leader, Cynthia Viteri, introduced the legislation in 2003 as a “measure to enforce prisoners’ judgment”—believing, as so many do worldwide, that so-called “professional criminals” might theoretically think twice about engaging in illicit activities that would translate directly into being “taken to jail and the key thrown away.” In practice, however, the legislation was passed in a series of collaborations and backroom deals between congresspersons and members of the Supreme Court in league with the PSC, all of whom sought to guarantee that all criminal suspects would receive their day in court no matter how long it took—directly undermining the authority of Article 24 in Ecuador’s 1998 Constitution, which set limits for the number of years Ecuadorians and foreign nationals could spend without sentence in state penitentiaries.

The National Congress, perhaps sensing the onset of a political shakeup (I can’t know for sure), eliminated detencion en firme altogether on October 23rd, 2006, shortly before Correa was formally installed as president. It is true that prison reform was central to his campaign promises for the presidential office—in particular, to respect the primacy of limitations and protections against detención en firme (i.e. the primacy of Article 24, which I describe at length in the article). One might even claim that his 2006 political platform on prison reform was just as central to his “electability” as the incorporation of indigenous wisdom and the techniques of environmental stewardship within the administration the state, the promises of which are well-discussed in Marisol de la Cadena’s CA article on Ecuador’s new Constitution (in particular its respect towards indigenous “earth beings” as a new ethical paradigm for intercultural citizenship). Correa’s administration is nothing short of a powerful opening to multicultural interests within the state. Yet one of the most unexpected, difficult-to-explain outcomes of the arrival of Correa’s “21st Century Socialism” is the continuance, and, to a certain degree, even the expansion of punitive containment policies in the Social Christian Party electoral stronghold of Guayaquil—the precise location where I carried out my ethnographic investigation. This turn of events demands careful explanation.

In the years between 2003 and 2006, the population of indefinitely detained subjects in Ecuador practically grew on a sine curve as a result of detención en firme. One report placed the yearly number of the state’s juridical hostages at 8723 in 2003 and 12,693 in 2004, but after the abolishment of detención en firme in 2006 the numbers immediately dropped to 10,510 as those prisoners who were indefinitely detained more than a year on less serious charges were slowly, cautiously given their ticket out of the jails. The numbers of the preventively imprisoned would continue to diminish as Article 77 and 78 of the New Constitution gave prisoners new rights to defense lawyers and civil protections; according to one newspaper article, 28% of the preventively imprisoned were granted their liberty between December 2007 and June 2008. At the same time, the Supreme Court controlled by the establishment parties in opposition to Correa’s administration—the PSC and PRE—attempted to block the release of prisoners, claiming that Congress had no authority to mandate the emptying of the prison system. In Quito and Guayaquil, prisoners held prayer vigils and hungers strikes to protest the federal government’s lack of speed and their rights to be immediately released. Correa in turn threatened to disband the Supreme Court unless they attended to all cases of the preventively imprisoned in an expedited process, presaging a contentious event that would take place shortly before he organized a new Constituent Assembly to create a new national constitution. A full year later, the prison population had been reduced from 18,000 to roughly 11,000.

A main part of Correa’s policy platform towards the criminal justice system has been a concerted effort to decrease the numbers of individuals indicted and sentenced on drug-running charges—part of his opposition to the US-led international “War on Drugs” that was of a piece with removing US Southern Command military base from Manta, Ecuador in 2009. The president and Congress increased the quantity of cocaine in one’s possession that would legally qualify as “drug trafficking” from two grams to two kilograms; simultaneously, Correa’s regime banned all charges for the actual consumption of illegal narcotics. These interlinked measures had an immediate and salubrious outcome on prison overcrowding: releasing from federal prisons all criminal suspects or individuals charged as “mules”—i.e. those who transport drugs from one country, region, or neighborhood to another. Most female prisoners were as a result immediately released from prison. At the same time, Correa increased diplomatic pressure with other countries to repatriate foreign nationals who were incarcerated without sentence. According to prison ethnographer Jorge Nuñez Vega (personal communication, 8/26/ 2010), Correa’s administration generally drew unfavorable press for these policies across the regional and national media—apart from his own, state-sponsored radio and television channels. In even more recent years, the president has begun to subsidize NGO Foundation and police efforts to institute neighborhood-specific anti-crime initiatives, which seem from the initial reports to be matched with increased levels of “assassinations,” “robberies,” and the cumulative rise in the public fear of crime and the quota of daily criminal arrests (Nuñez Vega, ibid)—a process that maps quite well onto my article’s diagnosis of the discourse of “urban renewal” lying at the center of the regime of punitive containment. In other words, what is taking place at the national level across the Correa administration’s variety of anti-neoliberal reforms depends fundamentally upon the flexible structure of the NGO and security organizations, a pair of institutional entities whose revanchist mechanisms remain intact though the neoliberal government policies that midwifed them are no long dominant on the national scene.

This turn of events in the national context, however, largely fails to explain what was taking place in Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city and the area where I carried out my fieldwork. Under the neoliberal autonomist regime of mayor Jaime Nebot, a new Guayaquileño NGO Foundation, The Corporation for Citizen Security, along with the city’s Business Camera, jointly funded the construction of a new “maximum security” prison on the grounds adjacent to the Penitenciaría del Litoral. While the auxiliary prison space was designed to house only individuals sentenced with serious crimes, its mere presence, as in a kind of pressure release valve on the Penitenciaría complex as a whole, had the effect of immediately stimulating a demand to incarcerate any suspects, no matter how petty the crime—while respecting new federal protections against indefinite incarcerations. As of the middle of June 2007, six thousand prisoners were being housed in the Penitenciaría, whose capacity to warehouse suspects was almost doubled. (During the time of my field research on the inside, the Penitenciaría housed nearly four thousand inmates.)

The account I have provided goes a long way towards showing that preventive imprisonment is a core neoliberal policy reaction to crime in autonomist zones of those countries now associated with populist socialism at the level of state politics. What is particularly frightening however is the flexibilization of the NGO foundations under the new political-economic order as a whole, as their diffuse research and security apparati continue to generate more crime and urban unrest (see Goldstein 2010 for a recent appraisal; Jorge Nuñez Vega is also writing a monograph under contract with FLACSO-Ecuador on the revanchist discourse of “citizen security”). In other words, under Correa’s watch a variety of police and civil-managerial bodies, operating at the level of the municipality, continue to identify and subject the same caste of urban targets described in my article (the poor, marginally employed youth of color) to special forms of discrimination and persecution inside and outside the walls of the penal state apparatus.

List of Academic Works Mentioned Above:

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998 Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press

Badiou, Alain. 2003 Saint Paul: the Foundation of Universalism. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press

Bataille, Georges. 1991 The Accursed Share, Vol. 1: Consumption. New York: Zone Books

Dubreuil, Laurent. 2006 “Leaving Politics: Bios, Zöë, Life” Diacritics, v. 36, n.2

Edmonds, Alex. 2007 “ ‘The Poor Have the Right to be Beautiful’: cosmetic surgery in neoliberal Brasil” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13(2)

Esposito, Roberto. 2006 “The Immunization Paradigm” Diacritics. V. 36, n. 2

Garces, Chris. 2007 “The Ethical Turn… to Saintliness?” Anthropology & Humanism v. 32, n.2

Garces, Chris; Alexander Jones. 2009 “Mauss Redux: from warfare’s human toll to l’homme total” Anthropological Quarterly. v.82 n.1

Girard, Rene. 1989 The Scapegoat. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Goldstein, Daniel M. 2010 “Towards a Critical Anthropology of Security” Current Anthropology. v. 54, n. 4

Heyd, David. 2009 Supererogation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lévy-Bruhl, Lucien. 2010 Primitive Mentality. General Books LLC

Mahmood, Saba. 2001 “Feminist Theory, Embodiment, and the Docile Agent: some reflections on the Egyptian Islamic Revival” Cultural Anthropology v. 16, n.2

Nancy, Jean-Luc 1991 “The Unsacrificeable” Yale French Studies no. 79

Robertson Smith, William. 2010 Lectures on the The Religion of the Semites: First Series. the Fundamental Institutions. Nabu Press

Strenski, Ivan. 2002 Contesting Sacrifice: Religion, Nationalism, and Social Thought.Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Strenski, Ivan. 2003 Theology and the First Theory of Sacrifice. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill

Valeri, Valerio. 1985 Kingship and Sacrifice: ritual and Society in Ancient Hawaii. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Valiani, Araafat. 2010 “Physical Training, Ethical Discipline, and Creative Violence: Zons of Self-Mastery in the Hindu Nationalist Movement” Cultural Anthropology v. 25 n. 1

Photo Essay

No. 1 This following photo essay by Chris Garces culls images related to a 2003 prison protest in Guayaquil, Ecuador in which the participating inmates had themselves literally crucified in order to denounce their indefinite, unconstitutional detainment. It provides a window into the largely obscure rationale and the hidden growth of penal state politics.

No. 2 This image shows a prison guard escorting his wards from one cellblock to another. The prison guard is a powerful figure, absolutely central to the inmates' 2003 intervention, as a key liaison between multiple mafia hierarchies and the penitentiary's titular administration.

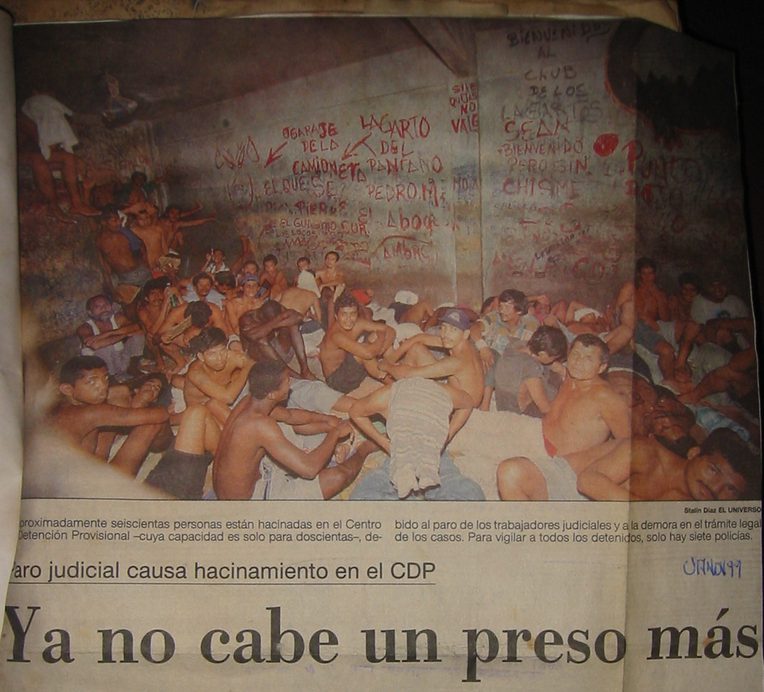

No. 3 "Prison overcrowding in Ecuador reached its first major crisis in 1999, when 5,558 [individuals]... found themselves detained without sentence. By late 2003, the situation had grown much worse."

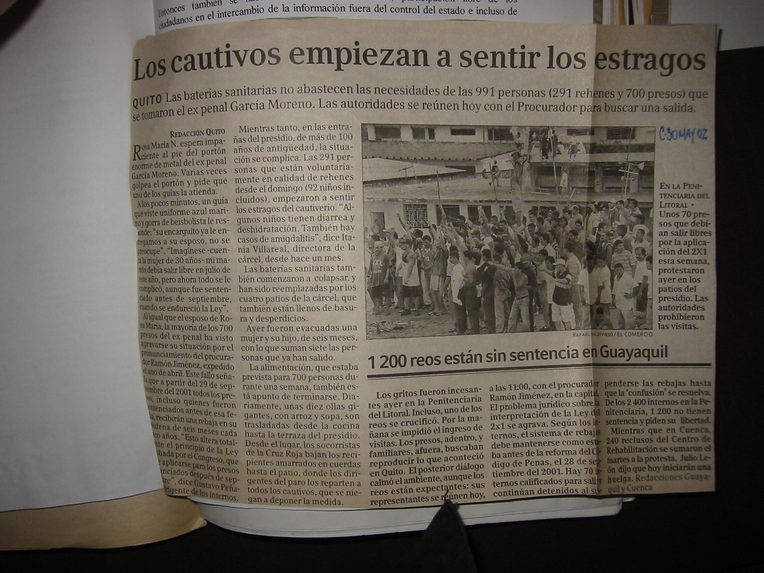

No. 4 "Earlier in 2003, prisoners [living] in this state of exceptional incarceration responded to their abject legal condition with the announcement of imminent revolts.... Well aware of their [prisoner] compatriots’ [failed mutinies], Guayaquil’s preventively incarcerated now sought “more peaceable” measures to wrest what they considered their inalienable rights from an unwilling state."

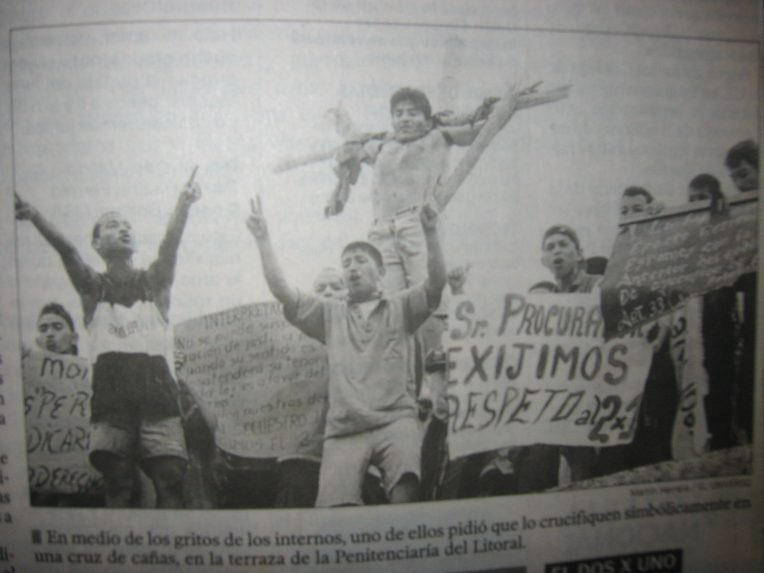

No. 5 "The protest tactic of staged crucifixions ... grew popular in Guayaquil during the 1980s and 1990s, with symbolic victims tied—although not nailed—to wooden crosses."

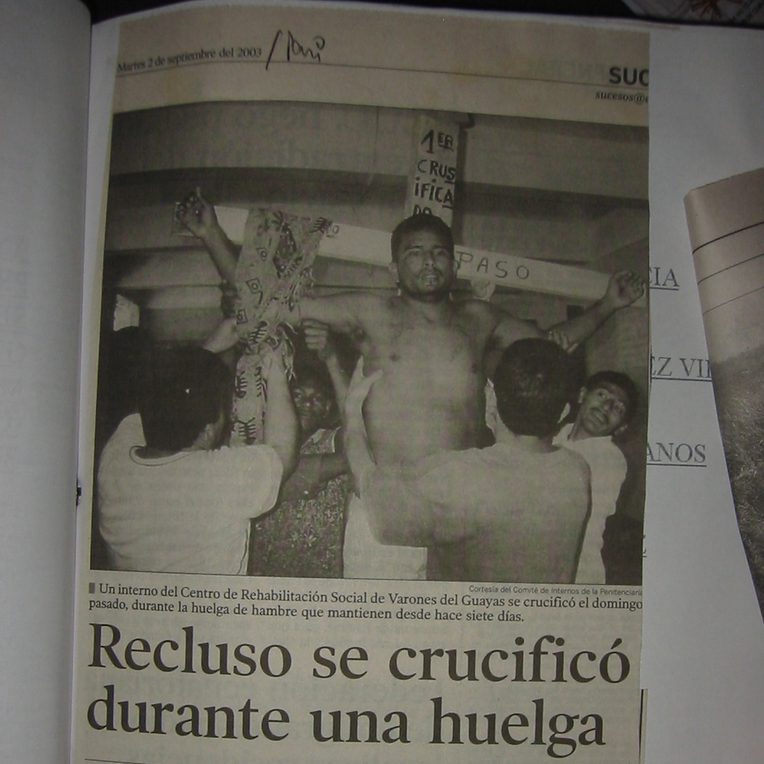

No. 6 "Despite their small numbers (involving 34 out of the 1,500-plus preventively incarcerated in Guayaquil’s Peni), the inmates’ gruesome spectacle captured the attention of multiple publics in Ecuador as few stories from prison manage to do."

No. 7 "[T]he crucifixion protests’ juridical success was contingent on a deeper series of moral exclusions: not only were guards’ interests in facilitating the [prisoners'] campaign absolutely illegible..., so too was the role of foreign nationals, accorded entirely different privileges within a shared space of confinement."

No. 8 "Most cellblocks have organized themselves into shadow networks... that not only manage the flow of narcotics, money, and weapons but also engage in a widespread and unchecked practice of blackmail, theft, and torture known as sometimiento ('the subjugation')"

Related Readings

The following is a short bibliography of readings on preventive imprisonment in Latin America:

Breeden, George. 2009 "¿Qué es la Prisión Preventiva?" Prison Fellowship International (October)

Carranza, Elías. 1997 (editor) Delito y seguridad de los habitantes, México D.F.: Siglo XXI/ ILANUD/ Comisión Europea.

del Olma, Rosa; James Cavallaro; Anthony Bottoms. 1999 (contributors) "Prisons and Rehabilitation: Current Conditions and Future Prospects" Panel Session VII, Conference on "Rising Violence and the Criminal Justice Response in Latin America." http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/violence/memoria/session_7.html

Duce J. Mauricio; Cristián Riego R. 2009 Prisión Preventiva y Reforma Procesal Penal en América Latina. Santiago: UDP.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. 1997 "Chapter VII: the Right to Personal Liberty" in: Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Ecuador. Washington, DC: OAS/ICHR.

Salla, Fernando; Paula Rodriguez Ballesteros, et. al., 2009 "Democracy, Human Rights and Prison Conditions in South America" Report: Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, May 2009. http://www.cidh.org/countryrep/ecuador-eng/chaper-7.htm