This post builds on the research article “The Currency of Failure: Money and Middle-Class Critique in Post-Crisis Buenos Aires,” which was published in the May 2015 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published several articles on studies on the anthropology of money, value, and circulation including Virginia Dominguez’s “Representing Value and the Value of Representation: A Different Look at Money” (1990); David Pedersen’s “The Storm We Call Dollars: Determining Value and Belief in El Salvador and the United States” (2002); and Nicholas D’Avella’s “Ecologies of Investment: Crisis Histories and Brick Futures in Argentina” (2014). See also Oren Kosansky’s “Tourism, Charity, and Profit: The Movement of Money in Moroccan Jewish Pilgrimage” (2002); Douglas Holmes’ “Economy of Words” (2009); and Karen Strassler’s “The Face of Money: Currency, Crisis, and Remediation in Post-Suharto Indonesia” (2009).

Cultural Anthropology has also published many essays on neoliberalism and finance, including Peter Cahn’s “Consuming Class: Multilevel Marketers in Neoliberal Mexico” (2008); and Daromir Rudnyckyj’s “Spiritual Economies: Islam and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Indonesia” (2009); and Hadas Weiss’s “Homeownership in Israel: The Social Cost of Middle-Class Debt” (2014).

About the Author

Sarah Muir is Term Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Barnard College. Her work examines the practical logics of economic investment, ethical evaluation, and political critique, with a particular focus on social class and financial crisis. Situated at the intersection of linguistic, political-economic, and historical anthropology, her research is grounded in ethnographic fieldwork in Argentina and the United States. She is currently finishing a book manuscript entitled Argentine Afterword: Class, Critique, and the Experience of Perpetual Crisis, which examines the emergence of a national middle-class public in the aftermath of Argentina’s 2001–2002 financial crisis. Muir is also researching a new project called Corrupted Futures: Pension Politics and Financial Ethics in Buenos Aires and New York City, which interrogates struggles over the restructuring of pension plans, conceptualized as key institutions of intergenerational investment and social obligation.

Interview

Marianinna Villavicencio: In the article, you present the middle class through a variety of professions—nurses, bus drivers, school teachers, retirees, young mothers, amateur actors, etc.—some of whom mention their immigrant background. Notably, you present the post-crisis middle class as tied to practices of cultural distinction, ranging from trading self-reflexive critiques of the Argentine national project to embracing ideals of inter-class solidarity. Given all of this, who constitutes the middle class in Buenos Aires? Are there other kinds of identities, besides class, at play here?

Sarah Muir: I should emphasize that I don’t approach middle-classness as an identity but rather as a public. That distinction makes a difference because my argument does not concern a determinate set of individuals situated within something called “the middle class,” whether by virtue of their self-identification or my analytical objectification. The idea of a public points not to a set but to a collectivity that is always emergent because it must be continually produced through practices of address and attention. Classic conceptualizations of publicity have examined discursively constituted publics. I argue that the post-crisis Buenos Aires middle class emerged out of particular discursive genres to be sure (psychoanalytic and conspiracy theories, most saliently) but also out of non-discursive genres of practice (such as shifting engagements with embodied and material stores of value). In bringing together within one analytical purview the discursive and non-discursive practices of this middle-class public, we can begin to see how there is indeed much more than class (in the sense of an identity) at work here. Transgenerational narratives of immigration and thwarted upward mobility, for example, point not only to the shifting institutional grounds of social welfare but also to the longstanding and highly racialized embrace of European origins and correlative rejection of indigeneity and autochthony that is summed up in the popular saying, “We Argentines are descended from the boats” (Los argentinos descendimos de los barcos).

MV: You write about the desire to “escape money” and to reject an “aesthetic of consumerism” (325). Are you suggesting that a new ethical subjectivity emerged in post-crisis Buenos Aires? Could you expand by providing some examples of how “the ethicization of unremunerated activities propelled an efflorescence of volunteerism and ‘solidarity building’ initiatives”?

SM: I wouldn’t argue that this ethicization is entirely novel. In fact, it possesses a close family resemblance to middle-class practices in a number of other times and places, including earlier historical moments in Argentina. However, in this particular context, it constituted a rather paradoxical mode of class distinction, for it unfolded in a context marked not just by material impoverishment per se but more importantly by a dramatic calling into question of the grounds on which the privileged relationship between the middle class and the nation had long been predicated. My book manuscript, Argentine Afterword, takes up these questions in far greater detail. To anticipate an argument I make there, solidarity projects were oriented toward ameliorating conditions of poverty, social marginalization, and political disenfranchisement. However, due to the process of revaluation that I describe here in this article, those projects frequently posited subjective transformation over material redistribution as the central means of addressing the problem of inequality. As such, solidarity projects purported to construct an egalitarian national public but often reproduced (with somewhat shifting valences) extant logics of distinction.

MV: You argue that “the positive revaluation of self-cultivating practices” are “evidence of practical reasoning, through which people grappled with the logistical and interpretive problems” that arose with the collapse of the peso (137). Were you able to look at some of the ways that other socioeconomic classes coped with crises?

SM: My research focused squarely on the articulation of crisis and the middle class. I did so because, from the very beginning, this event and this public were defined with respect to one another. What’s more, the privileged relationship between crisis and the middle class is not unique to this context; we can find many such examples because financial crises play havoc with national currencies, which are a key medium of middle-class investment in project futures (whether individual, familial, or national). Of course, the socioeconomic positions of people participating in the post-crisis middle-class public varied widely and that variance itself shifted over the four years of my study (2003–2007). That variation points to the broader, supposed problem of middle-class heterogeneity, which has long vexed scholars and compelled many to take up positions either defending or rejecting the analytic utility and historical reality of “the middle class.” There have been many studies that correlate levels of social, economic, and cultural capital with strategies for coping with different sorts of economic challenges. However, and to return to my answer to your first question, my aim is not to relate middle-class subjects to the objective conditions of a currency crisis. Rather, I aim to account for the processes out of which “crisis” and “the middle class” emerged. That shift in approach means that heterogeneity need not pose an analytical problem: by tracking practices like psychoanalytic and conspiracy theorizing, we can see how a middle-class public emerged out of a socially heterogenous field.

MV: At various points in the essay, you mention that your informants understand their suffering to be part of a larger, failing global system. A veterinarian, for example, asserts that “Our money is part of a global fantasy network.” Nonetheless, despite this understanding, they continue to maintain confidence in the dollar “as the ideal type of monetary form” (329). Why do you think this is?

SM: I’m not sure I can say why this was the case. However, I can speak to how that seemingly untenable confidence was maintained. What is so interesting is that confidence was maintained not despite but through critique. I take this as pointing toward a paradoxical resiliency in liberal capitalism that we haven’t fully theorized and that requires us to pay far greater attention to the logics of our own critical and evaluative practices as much as to those of the people we work with. After all, the popular theoretical practices I describe in this article are not so dissimilar to the interpretive practices of anthropology as a discipline of critical interpretation.

MV: You mention that in post-crisis Buenos Aires “suspicious interpretation constituted a common social practice” (319). Did this play a major role in or complicate the way you negotiated your role as an anthropologist? How did this shape your relationships with informants?

SM: The willingness to engage in ongoing, open-ended interpretation was a boon to my research, because people were extraordinarily disposed toward talking to me about a very wide range of issues, including topics I would have thought quite sensitive. In fact, I regularly received phone calls from people I had yet to meet, who had tracked me down so that they might participate in my study and offer up their own opinions. In general, the commonplace quality of suspicion worked in my favor, for it helped render my project commensurable with the interpretive projects of my informants.

MV: Related to the previous question, were you ever the subject of any of these theories or psychoanalyses? Did you ever construct and circulate your own conspiracy or psychoanalytic theories?

SM: I don’t know that I ever constructed and circulated my own conspiracy and psychoanalytic theories. However, I did very regularly bring up in interviews and casual conversations theories I had heard elsewhere. In fact, introducing these sorts of textual artifacts became an important research technique, one that elicited a wealth of commentary precisely because it partook of the discursive genres people routinely mobilized in their daily interactions.

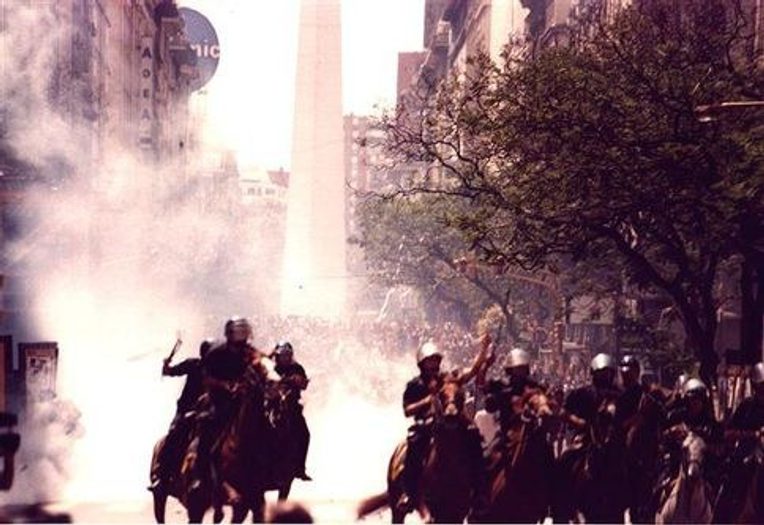

Picture Gallery

Questions for Classroom Discussion

1. The study of finance is often seen as highly quantitative and devoid of personal agency/actors. How does Muir create an anthropology of finance that keeps the focus on lived reality and human experience?

2. How does Muir define a crisis? How is this tied to the monetary form itself?

3. After reading the article, has your understanding of money changed? How does Muir describe money? How do her informants conceptualize it?

4. In what ways is morality intertwined with the practices of critique that surrounded the crisis in Buenos Aires?

5. What role does suspicion play in the “paradoxical resiliency” of the “representational economy of liberal capitalist modernity” (p. 329)? How can suspicion (as opposed to sincerity) change the way we analyze the representational economy of capitalism?

6. Beyond the post-crisis Buenos Aires middle class, can you think of other publics characterized by similar genres of crisis talk?