The Depths of Geological Fieldwork

From the Series: Geological Anthropology

From the Series: Geological Anthropology

Throughout the summer of 1976, British geologists working in Ecuador on a geological mapping and mineral exploration project were finishing key parts of their remaining work. That July, Brian Kennerley, who had been leading the British mission since the late 1960s, relayed to directors at the British Geological Survey (BGS) that his team was completing “density-depth” profiles of northern Ecuador. Ecuadorian officials, he said, agreed that such information would “provide useful data in helping to understand the structure of the northern Andes in Ecuador.”1

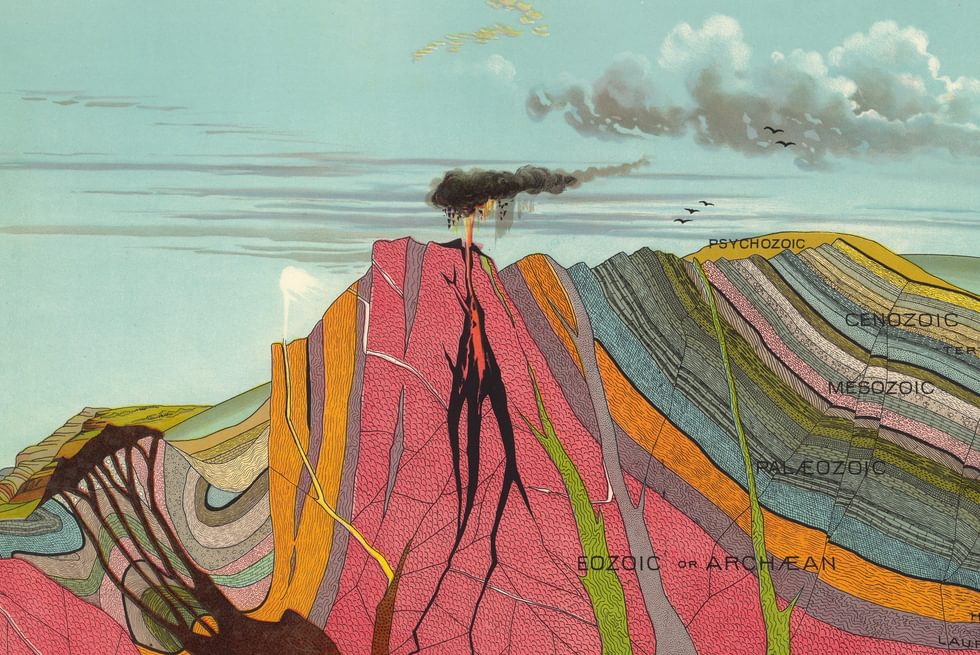

Notions of depth were key here. Depth was both a way to know and produce the structure of the Ecuadorian Andes—something that could help identify areas of resource concentration and be politically useful for Ecuadorian officials. In this fragment of correspondence from a British mapping project, we see a theme that has been recurrent in the scholarship on the underground: the processes through which subsoil territory is imagined and endowed with political and economic significance (Elden 2013; Rogers 2015).

Depth not only evokes vertical space. It also calls to mind a sense of intensity, gravity, and distance. I propose that we think about depth as not only a product of geological practice but also as a constitutive feature of geological fieldwork. While we tend to locate understandings of depth in relation to the subsoil, a very different articulation of depth breaks through the archival grain of British correspondence at the end of August 1976. It is a hand-written note, faxed from one of the British geologists in Ecuador to the head of the Overseas Division in London. The note relays the news of Kennerley’s death.

Dear David:

No doubt you have received the tragic news via telex and the press of Brian’s death in a car accident in Colombia. It was a shock to us all . . . We do not have any details of the crash other than that the car was in a collision with a tractor in Cali . . . Brian was killed outright and Margaret and the children are in hospital. The Embassy spoke to Margaret Sunday morning and she has fractured ribs, the two boys Garry and Keith have broken noses and superficial injuries. Clare [the daughter] is unconscious with a suspected fractured skull but is saying a few words. Norma and Bill have gone up to Cali to see what can be done . . . 2

Shock and loss resonate strongly here and in the correspondence that followed. In the wake of this geologist’s death, social and family relationships that were largely sidelined in everyday accounts of geological labor took on increased prominence. I encountered the faxed letter about Kennerley’s death while conducting archival research in a poorly lit room of the British Geological Survey in late December 2012. It left me quite shaken. Reflecting on my own time doing fieldwork in Ecuador since 2000, I had come to empathize with Kennerley’s experience in the field, particularly the tensions between investment in Ecuador and the desire to go home. Kennerley, thirty-nine at the time of his accident, had been eager to return to the UK after six years working in Ecuador. But the directors at BGS encouraged him to remain until the end of the British mission. They assured him that a second tour as residential leader would enhance his professional stature; with that experience, he could build a career within the Overseas Division beyond his current photo-geological expertise. Like the dialectics between ethnographic research and the formation of anthropologists, the scope of Kennerley’s fieldwork was directly related to what sort of geologist he could become within the British Geological Survey.

The field that Kennerley lived, worked, and died in was not a given. As anthropologists have outlined, the sense of distance and boundary crossing that typify fields of inquiry are not natural, but sentiments that materialize in the very language and categories through which researchers demarcate self and other, home and away (Gupta and Ferguson 1992). The field that defined the work of British geologists in Ecuador was one with distinct colonial traditions associated with the practice of British geology. Its dimensions in the 1970s took shape under the discursive metrics of British aid and the project of developing the Ecuadorian underground as both an object of economic intervention and a sphere of state-sanctioned scientific knowledge. Notions of distance and separation were further reinforced in the everyday correspondence between BGS headquarters and the mission in Ecuador—the need for hardy Land Rovers, the distrust and frustration through which British geologists described their Ecuadorian counterparts, and the sense of Ecuador’s marginal position in terms of resource discovery.

Kennerley didn’t just die. He died in the field. He died while doing fieldwork. This not only magnified the sense of loss and tragedy, but reshaped the contours of British geological practice. The abrupt intimacy of death collapsed and inverted the personal and professional spheres that characterize fieldwork. Buried in Quito, Ecuador’s capital city, Kennerley remained present, the meaning of his life coming to shape the British mission. By the late 1970s, some Ecuadorian officials became skeptical of the BGS program to produce base level geological maps, wanting the British “to produce results [mineral deposits] rather than fancy maps.”3 In internal discussions about the fate of the British program, BGS geologists framed their desire to finish the mapping project around Kennerly’s legacy. As one wrote, “ . . . in a sense we owe it to Brian to make every effort initiated by him be brought to fruition and published if possible before the team leaves Ecuador.”4 Situated in relation to “Kennerley’s work,” an underlying sense of obligation thus became embedded in British geological practice and a valued element in appraisals of maps of Ecuador’s underground.

It can be easy to hold up a geological map, of Ecuador or anywhere else, and analyze it as a vertical dimension of state territory and control. Kennerly’s death, however, calls for greater reflection about the ways we think about the making and significance of geological maps and mapping projects. It brings to the fore other registers of density and depth that are associated with geological fieldwork, from the very composition of the geological field to the shifting loci of meaning that endow subsoil imagery with significance.

1. Brian Kennerley to Masson Smith, July 26, 1976, IGS/OD/22/1/6, Archives of the British Geological Survey.

2. Jeff Aucott to David Bleackley, August 23, 1976. IGS/OD/22/1/6, Archives of the British Geological Survey.

3. PJ Spiceley to William Hobman, October 28, 1976, IGS/OD/22/1/6, Archives of the British Geological Survey.

4. David Bleackley to Jeff Aucott, 12 October 1976, IGS/OD/22/1/6, Archives of the British Geological Survey.

Elden, Stuart. 2013. “Secure the Volume: Vertical Geopolitics and the Depth of Power.” Political Geography 34: 35–51.

Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson. 1992. “Beyond ‘Culture’: Space, Identity, and the Politics of Difference.” Cultural Anthropology 7, no. 1: 6–23.

Rogers, Douglas. 2015. The Depths of Russia: Oil, Power, and Culture after Socialism. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.