Many environmental problems in the twenty-first century seem practically unsolvable—pollution, corporate monopolies, climate change. Part of our responsibility, as teachers and students of anthropology and as global citizens, is to understand the breadth and the depth of those problems in all their complexity. As instructors, however, we recognize that in doing so we run the risk of leaving our students feeling guilty, stressed out, and defeated. Even when they are willing and eager to make a positive change in the world, they might fear their personal actions will not be “enough” or that their well-meaning efforts will be culturally inappropriate or ethically problematic. How can we teach our students to think critically about environmental issues, and to combat the environmental reductionism so commonplace within policy-making spheres, without leading them down a path of cynicism or fatalism?

In an introductory class in environmental anthropology that Alyssa (faculty instructor) and Lai (graduate student instructor) taught in the Spring of 2024, we asked our students to channel those feelings of eco-paralysis into meaningful action through “The Environmental Wayfarer Project,” named after Trevor Durbin’s (2015) reflections on teaching a class on the Anthropocene. Inspired in large part by Sarah Osterhoudt’s (2021) “bright spot ethnography,” the Environmental Wayfarer Project is a semester-long, group-based assignment that prompts students to identify a particular environmental problem that they observe in their university community and to articulate how they can be a part of a meaningful response to it.

“Meaningful” is the operative word here. Students often assume that solutions must be “perfect” for them to count, a notion that can exacerbate eco-anxiety. Against this assumption, we defined a “meaningful response” as action that has two main characteristics. First, it recognizes that the ways some groups understand the nature of a “problem” might include their concerns while excluding those of others. Second, it attends to the distinct resonances of this problem across different scales and perspectives, linking experiences within our own communities to those of different geographic contexts.

This is a tall order! But by defining “solutions” as meaningful responses, they become far more within reach. Thinking about inclusions and exclusions, as with thinking across scales, are not necessarily intuitive to students in an introductory level class. To guide our class towards their meaningful responses, then, Alyssa designed the project in five manageable parts. Lai randomly divided the class into groups of four to five (so as to simulate a meeting among community members) and guided the students through each step. In what follows, we describe the components of the project, list a few inspiring ethnographic sources, and discuss how our class responded and the challenges they faced. We conclude with the feedback we received, solicited through their course evaluations.

Part 1: Design a Group Contract

Lai kickstarted the project in discussion sections by creating opportunities for team building. She asked students to reflect on their personal strengths, brainstorm how to best proceed given each member’s availability and accessibility, and exchange contact information. By the end of the week, the students submitted a signed “group contract” outlining how group members will relate to each other, share the workload, enhance productivity, and navigate potential moments of conflict using a template adapted from the University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching. The contract was meant to abate common concerns around inequitable divisions of labor in group work. We encourage other instructors to consider incorporating the contract in their grading schemes.

Part 2: Identify an Environmental Problem

For Part 2, we asked our students to identify and describe an environmental issue on campus in a 150- to 300-word essay. The only condition was that these had to be issues that they cared about. Our class chose a number of fascinating problems affecting the University of Michigan: invasive species in the Nichols Arboretum, water pollution in the Huron River, food waste in the MDining system, DTE’s corporate energy monopoly in parts of Southeast Michigan, overreliance on road salt during winter, insufficient public transportation between Central and North campus, ongoing construction of high-rise buildings throughout university grounds, and the differential impact of light pollution among racialized communities across town.

Notably, identifying an environmental problem was not an altogether straightforward task. A few groups got ahead of themselves and listed perceived solutions rather than environmental problems. For example, some proposed to work on “sustainable transportation” and “retrofitted homes”—choices that suggested the misinterpretation of “environmental challenge” for “environmental problem”—i.e. confusing the “challenge of getting more support for sustainable transportation” as the problem. Seeking to steer students away from presumed solutions, Lai directed them to “carbon emissions” or “lack of investment in sustainable transportation” and “energy consumption in residential buildings” instead.

Part 3: Notice Inclusions & Exclusions

Part 3 is where students learn to apply “intersectional” approaches to environmental anthropology (Vaughn, Guarasci, and Moore 2021). Following independent research, in a collectively written 300- to 500-word essay, groups were tasked with addressing the following questions: How is your issue a “problem,” and according to whom? What “solutions” have been offered to this problem, what sorts of actors have come to define those solutions? Have there been disagreements? Have there been perspectives systematically marginalized? We used the works of William Cronon (1996), Paul Nadasdy (2005), and Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga (2014), in particular, to demonstrate that what counts as an “environmental problem” or as a “solution” depends on who’s included in the conversation.

Lai facilitated this process by posing her own set of questions: “Whose voices are foregrounded?” “Whose are silenced?” and “Environmentalism for whom? According to whose standards or ideals?” Already at this early stage of the project, students encountered several opportunities to see how environmental decision-making can either privilege or exclude certain perspectives and experiences based on differences across race, gender, class, sexuality, dis/ability, and histories of coloniality. For instance, commonly proposed solutions to carbon emissions from private vehicle use include expanding bike lanes, purchasing more electric vehicles, or incentivizing public transportation ridership. However, as students discovered with the help of their graduate student instructor, these solutions at times discounted those with mobility impairments unable to ride bikes or those whose residence was not conveniently located along public bus routes. In addressing issues of accessibility, another group found that students were prohibited from carrying necessary medication and medical needles with them on public transportation.

Part 4: Chart the Scale of the Problem

Part 4, where students charted the scale of their environmental problem, is by far the most demanding and exciting aspect of the project. We took inspiration from Paul Robbins’ (2007) multi-scalar approach to the “political ecology” of the American suburban lawn and Max Liboiron’s (2021) attention to the “scalar fallacies” of recycling as a solution to waste. We linked the concept of “scales” with ethnographies that unearthed the invisibilized ties between Singapore’s land reclamation projects and sand-dredging in Cambodia (Novak 2020), or between industrial agriculture in the Global North and phosphorus mining in Banaba Island (Teaiwa 2014).

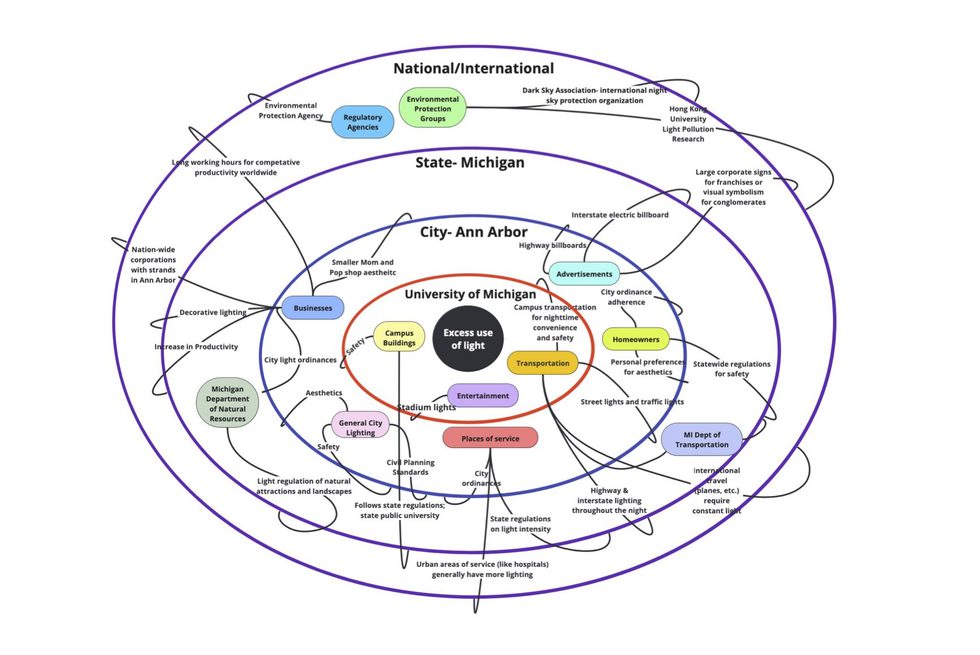

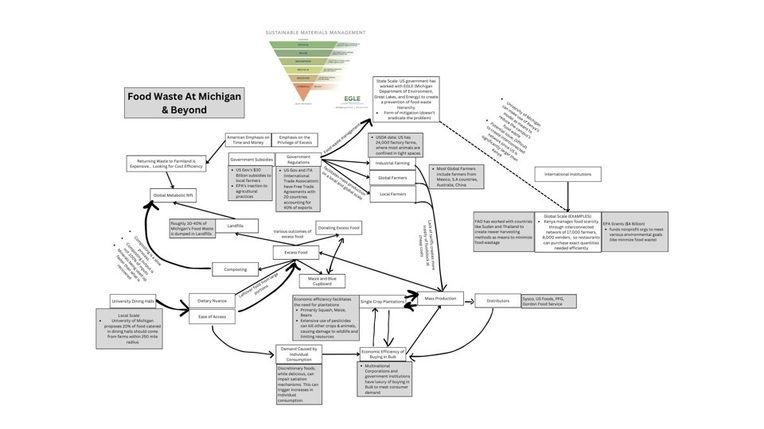

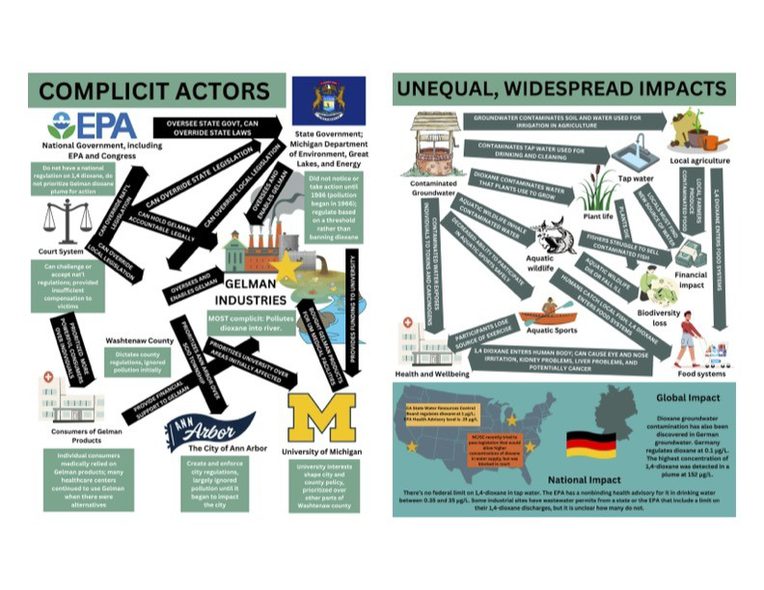

To accomplish this, we asked the class to conduct independent research and produce a visualization in the form of a flowchart via Miro, a storymap via ArcGIS, or an old-fashioned illustration. We explained that their goal should be to chart specific institutions, actors, and ordinances that linked their problem in Ann Arbor to other local, regional, national, and global contexts. For example, a group researching road salt in Michigan found that salt-mining in Alagoas, Brazil, contributed to ground sinking and extreme poverty. Another group researching DTE Energy found that coal and natural gas were sourced in part from the Powder River Basin in Montana and Utah, where toxic contaminants have been linked to higher rates of cancer and pre-birth defects. Images of our students’ exemplary scale charts on food waste and 1, 4 Dioxane pollution are below, as well as in this Miro flowchart on invasive grasses[1] and another on construction.[2]

We found that the class, especially those without prior exposure to anthropology or environmental studies, required some guidance in thinking across scales. For instance, students examining sustainable transportation did not intuitively trace the increased demands for electric buses on campuses to large-scale extraction of lithium, cobalt, and nickel on the African continent and elsewhere. Initially, students were unsure of how to begin thinking more broadly, so we guided them through a series of questions: ‘How has this issue arrived in Ann Arbor?’ ‘Which actors, institutions, or regulations are shaping policies and decisions around these issues?’ ‘Where else in the world does this problem arise?’ In section, Lai reminded them of the films that they had watched earlier in the semester, like Chai Jing’s Under the Dome, which captured how corporate influence over state environmental policies led to consequential impacts for mothers who were otherwise individually blamed for their children’s congenital diseases.

Upon incorporating feedback from the instructional team, students were able to draw these scaled connections more concretely. As one student described:

“I really identified with the concept of scale [because] in a lot of discussions of environmentalism, scale isn’t really mentioned, and I often find myself becoming apathetic to environmental issues because of it. Everything seems so bleak when the burden is placed solely on the individual rather than the institution, and I was very happy with how the course addressed this point.”

For instructors considering this activity, in-class brainstorming and guidance on research strategies can be helpful. Providing models of prior student work also clarifies the level of detail, specificity, and scope expected of the assignment.

Part 5: Identify a Meaningful Solution and Share your Findings

Part 5, the culmination of the project, prompted students to reflect on what it means to make meaningful contributions to an environmentally-just world. We posed the following questions: “Knowing what you do now about how your environmental problem and its proposed solutions include and exclude certain perspectives (part 3), and about how the scale of the issue draws our university community into tangled webs of complicity and responsibility beyond its bounds (part 4), what do you think would constitute a meaningful response?” In a 400- to 600-word essay, our students were tasked with identifying a specific organization, initiative, or campaign from anywhere in the world that offers a meaningful model for environmental problem-solving.

This line of thinking was directly informed by ethnographic works on citizen science by Adriana Petryna in post-Chernobyl Ukraine (2002), Aya Kimura in post-3.11 Japan (2016), as well as the recent documentary “The People vs. Agent Orange” (2021). All these sources encourage students to look beyond mainstream modes of environmentalism, such as the establishment of parks and nature reserves, the designation of certain locales as superfund sites, and the idea of government regulations as a panacea. We emphasized how these common “solutions” often gloss over the concerns raised in Parts 3 and 4.

Our students used the assignment to learn about an impressive array of “meaningful responses” from around the world. Initiatives like the Harvard Construction Mitigation Program and the Hong Kong University Light Pollution Collective include ordinary citizens in defining problems and articulating solutions. The Asia-Pacific Forest Invasive Species Network addresses the multi-scalar problem through inter-country cooperation. Several groups identified publicly accessible resources: complementary “Salt Watch” kits from the Izaak Walton League; food and pantry items from The Maize & Blue Cupboard; and free native seeds from the UM Seed Library. Other campaigns, like Ann Arbor for Public Power, invite citizens to imagine alternative energy infrastructures.

In keeping with the spirit of the project, we asked the class to prepare ten minute presentations sharing their findings as the final assignment of the semester. We explained that their primary goals, in addition to incorporating the feedback from previous assignments, were to get their classmates to recognize an environmental issue they may have never thought or cared about before, to help them appreciate the complexity of the issue, and to enlighten them about existing initiatives that they can join. Watching the presentations was the highlight of our semester. We were delighted to see our students speak on their environmental problems with confidence and expertise, and we were moved by the tangible sense of energy and optimism that filled the room. We learned that the University of Michigan does not follow city ordinances around light pollution because it is owned by the state, that the City of Ann Arbor’s dome-shaped street lights actually cause more light pollution than other alternatives, that the construction waste from campus eventually ends up in the Arbor Hills Landfill, that the University applies 2,400 tons of rock salt and 300,000 gallons of liquid deicer on city streets, and that experts believe this may have contributed to the Flint Water Crisis, among so many other critical facts about the city we call home. Not inconsequentially, we felt that the tables had surely turned, and the teachers had become the students!

Problem Solving with an Eco-Anxious Generation

We feel that we are only just beginning to reap the rewards of the Environmental Wayfarer Project. Academically, students expressed that the project clarified class concepts and helped them consider forms of environmentalism beyond U.S.-centric perspectives. One student found “expanding upon a local dilemma [by] scaling up the problem” to be a “very useful skill” that both “made the problem feel a lot more real” and “gave a sense of direction rather than hopelessness.” Relatedly, several noted that the project deepened their awareness of local political governance structures, making them “more invested in the environmental issues that our community here in Ann Arbor face.” For some, positive outcomes were interpersonal. One student wrote, “Once my group finished presenting, we felt so proud of the work we had accomplished.” Another enjoyed the collaborative experience, allowing them to talk with “people [they] usually would not have” and learn about topics they “would not have researched on [their] own.” Many learned the value of effective communication and equitable distribution of work, and at least one person felt they had made a “real friend.”

By assigning the Environmental Wayfarer Project for years to come, we hope our students will increasingly view themselves not only as members of environmentalist projects, but also as valuable contributors to it. In the 2024 Spring term, we began to see the seeds of that aspiration when two groups made plans to share their work publicly. For one group, the best outcome of the assignment was “the opportunity to potentially share an article to the Michigan Daily [the student newspaper] regarding our project as it would truly benefit our campus.” Most importantly, we hope that they bring with them a vision of environmentalism that is more attentive in its understanding of whose concerns should count, more capacious in its view of how global ecological fates are linked (albeit differentially), and more humble and more compassionate in its response.

Footnotes

[1] “Invasive Grasses in Ann Arbor Laws + Green Spaces,” Environmental Wayfarer Project Scale Chart, by Ava Tackabury, Dikembai Woodfill, Ruiyang Ling, and Jaydan Augustin. Reproduced with permission.

[2] “Construction,” Environmental Wayfarer Project Scale Chart, by Megan Okubo, Loree Chung, and Joseph Goslak. Reproduced with permission.

References

Chai, Jing. 2015. Under the Dome: Air pollution in China. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5bHb3ljjbc.

Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History 1, no. 1: 7–28.

Durbin, Trevor. 2015. “Loving, Eating, Teaching, and Wayfaring in the Anthropocene.” Engagement: A Blog Published by the Anthropology and Environment Society, October 21.

Kimura, Aya H. 2016. Radiation Brain Moms: The Gender Politics of Food Contamination After Fukushima. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution is Colonialism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Mavhunga, Clapperton Chakanetsa. 2014. Transient Workspaces: Technologies of Everyday Innovation in Zimbabwe. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Nadasdy, Paul. 2005. “Transcending the Debate over the Ecologically Noble Indian: Indigenous Peoples and Environmentalism.” Ethnohistory 52, no. 2: 291–331.

Novak, Sarah. 2020. “To Build a City-State and Erode History: Sand and the Construction of Singapore.” In Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene, edited by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, 61–78. Singapore: Ethos Books.

Osterhoudt, Sarah R. 2021. “Bright Spot Ethnography: On the Analytical Potential of Things That Work.” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture, and Politics 8, no. 1: 33–47.

Petryna, Adriana. 2013. Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Robbins, Paul. 2007. Lawn People: How Grasses, Weeds, and Chemicals Make Us Who We Are. Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple University Press.

Teaiwa, Katerina Martina. 2014. Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from Banaba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Vaughn, Sarah E., Bridget Guarasci, and Amelia Moore. 2021. “Intersectional Ecologies: Reimagining Anthropology and Environment.” Annual Review of Anthropology 50: 275–90.