The Epidemic Will be Militarized: Watching Outbreak as the West African Ebola Epidemic Unfolds

From the Series: Ebola in Perspective

From the Series: Ebola in Perspective

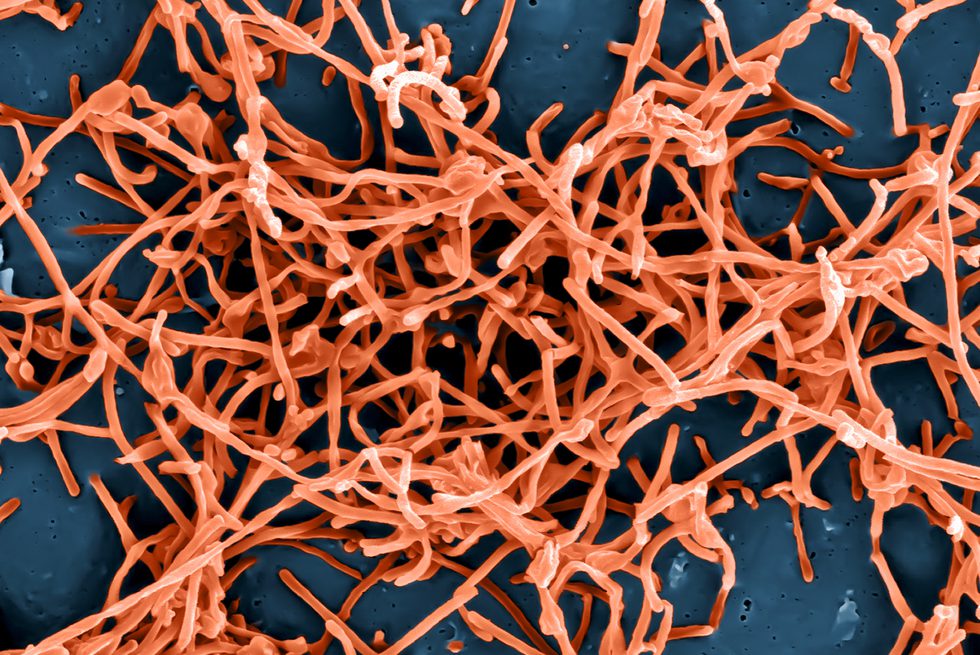

In mid-August 2014, infectious-disease physician Celine Gounder wrote an essay titled, “Remember the Movie ‘Outbreak’? Yeah, Ebola’s Not Really Like That.” On many counts, the headline (likely written by an editor and not Gounder herself) is right. The 1995 feature film, which stars Dustin Hoffman as Colonel Daniels, an American military virologist, chronicles the US government’s attempts to control the spread of Motaba, an Ebola-like viral disease, as it travels in the body of Betsy, a capuchin monkey, from rural Democratic Republic of Congo to a small town in California.

To date, Ebola’s index cases are linked to hunting and butchering infected animals, but most cases seen in the region stem from intimate interpersonal contact: caring for the sick, touching the dead, and preparing their bodies for burial. Moreover, as Gounder notes, the universal precautions used in most American hospitals, in addition to the human and material resources available to provide the supportive care required for treating Ebola’s symptoms, makes a rapid spread in the United States unlikely.

In Outbreak, the virus quickly mutates into an airborne disease as it jumps from Betsy to humans, leaving the US military and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention racing to locate and identify the vector, isolate cases, and contain potentially infected communities, while also manufacturing an effective treatment. The plot is propelled by rapid viral mutations and the equally rapid development of an effective drug. Vivid maps projecting a grim epidemic future reflect a frightening visual compression of time. As a film reviewerwrites, “See this map of the world with a bit of red on it? That's now. See this map of the world with LOADS OF RED on it? That's SOON. (*gasp*).”

Despite these differences between film and “real life,” some events in the film resemble those in the affected countries. State-sponsored violence against and criminalization of recalcitrant communities, the hyper-vigilance and policing of cross-border mobility, and (a return to) militarized and ‘securitized’ versions of public health are among those resemblances. In the film and in West Africa, the techniques of public health—investigation, surveillance, isolation and containment—collide with the medical ethics of care and compassion, as people initially fled a health system that isolated them from their loved ones, exacerbated their risk for infection, and viewed their bodies first and foremost as vessels for disease. (They would later be seen as resources from which to extract caring labor and immunity).

In the film, the US military encircles a fictional Cedar Creek, California, preventing the town’s residents from leaving and causing mass hysteria in the process. We learn very little about Cedar Creek or its history with military intervention and police violence in the film, but current events in West Africa show precisely how such history matters for local responses to the security elements of public health.

West Point, an informal settlement in Monrovia, has received considerable press during this outbreak for being violently opposed to the installation of an isolation unit in their community. It has a history of dispossession and marginalization, and unsubstantiated rumors have long circulated about the government wanting to clear slum housing. The Ebola isolation center placed in the community and the military quarantine erected at its borders deepened already tense relations between area residents and the government. In Sierra Leone, a cordon sanitaire around Kenema and Kailahun Districts remind many of the region’s residents of their eleven-year civil war, as they wondered whether they would be able to secure non-Ebola health care or access to regular goods and services, the prices of which have skyrocketed with severely restricted flight schedules and border and port closings.

Outbreak, while not overtly political, contains an implicit indictment of the Cold War politics in Africa and its consequences. The film opens in the late 1960s, in an “African mercenary camp” located in the fictional Congolese village of Motaba. Amidst bombs and gunshots, the camera pans over the bodies of sick mercenaries—black and white. At least one of the sick soldiers identifies himself as American. Precisely what battle was being fought is not disclosed, and for many American viewers, the presence of white American fighters in Zaire is likely an unremarkable plot element. The years are a bit off, but one might recognize a familiar story of US intervention in the country during its early years of independence from Belgium.

Civil conflict is not unimportant in the current outbreak. While it is common for people to be suspicious of official responses to the outbreak more generally, the shape that this suspicion takes is influenced by wartime experiences—even if indirectly. In the Liberian case, the mass exodus by elites during war resembles similar departures by elites through the Ebola crisis. Inadequate responses to the outbreak are paraded as evidence of poor leadership, fueling fire of pre-existing political grievances.

As the number of cases and deaths increased exponentially in August, Doctors without Borders (MSF), which had been the primary international responder for months, issued a call for governments to provide military and civilian capabilities to battle the epidemic. While MSF warned against using military personnel for containment or quarantine (i.e., military medicine without military might), it became clear that non-medical military solutions would be central to the US response—even as many observers express ambivalence about this move. In Outbreak, military solutions to a public health problem was a foregone conclusion: the question for our protagonist was not whether military intervention would be necessary or even desired but rather which kind of military response would be better for the greater good. As President Obama announces the rapid deployment of three thousand troops to Liberia, film and real life are again in sync, leaving no question regarding the character of US response: the epidemic will be militarized.