The Invisible Anthropologist

From the Series: Book Forum: A Possible Anthropology

From the Series: Book Forum: A Possible Anthropology

“I see you, John Jackson! I see you.” But how?

You see, I am an invisible man. No, I am not a thief, at least not just that, even when pilfering the opening line of Ralph Ellison’s (1952) classic novel about the profound conspiracy that is America’s seemingly unshakeable racial project. “I am an invisible man” helps me explain how and why I ever became an anthropologist, someone capable to being there and not-there, seen and not seen, at the exact same time.

It is this vanishing power, the gift of palpable evanescence, that defines a certain version of anthropological prowess. Being imperceptible can be valuable fieldwork practice, and it is one of Anthroman©™®’s most unteachable techniques. People talk to ghosts all the time, to gods and demons as well, even ones that only they can glimpse, which helps prime them for anthropological interrogation from those they cannot fully see.

Pandian’s wonderfully evocative and prescient book (A Possible Anthropology, Duke University Press, 2019) asks anthropologists to see and know ourselves anew, to revisit a few of the discipline’s practitioners and their practices (Malinowski’s embarrassingly xenophobic ethos and Jane Guyer’s openness to teacherly materiality and uncertainty; Lévi-Straussian acoustemologies, to borrow Steve Feld’s term, and Hurstonian conjuring of “cosmic secrets”) for ways of learning from living that anthropology, at its most ethically and politically expansive, requires. This is an anthropology, Pandian reminds us, which “thinks and works with the world at hand” (41). Anthropologists in a land enchanted and overrun by what some might dismiss as mere “things” eventually learn and appreciate that any objects taking shape in front of their anthropological gazes declare their own vexingly interconnected presence, “not things in themselves but things as they take shape in an encounter” (70). He calls this encounter “a mutual accommodation between the knower and the known” (64). And it might be added that one can feel oneself to be both (knower and known, seer and seen) or neither.

In Pandian’s subtle retelling of things, every word we compose is a function of what the anthropological project entails experientially, an “intimacy between knowledge and experience” (75). These words are incantations with productive force—and not just in the masterful prose of anthropological offspring such as Ursula K. Le Guin. Beyond the page, they haunt us in the field, mesmerize our students when delivered in front of the most susceptible of their lot, and serve as the gilded phrasings delivered from behind lecterns at academic conferences the world over. And it was at one such conference, an annual American Anthropological Association meeting not too many years ago, where my former student, now a tenured scholar with an international reputation, stopped me between sessions to say, with the softest of smiles as its backdrop, “I see you, John Jackson.”

I could see her, too. I think she knew that. I hope she did. I want to imagine such seeing as always reciprocal, another kind of “mutual accommodation,” only possible in the form of a judicious dialectic, a differently constitutive encounter. That she and I could see one another in a Marriott lobby somewhere might seem superficial and daft—or even slightly ableist. But that small and seemingly inconsequential moment (amid a sea of pattering anthropologists, their name badges beckoning strangers for momentary attention) has always stayed with me, maybe because it was so unexpected, so out of the blue, which is another crucial insight Pandian turns over in this text: the efficacy of serendipity.

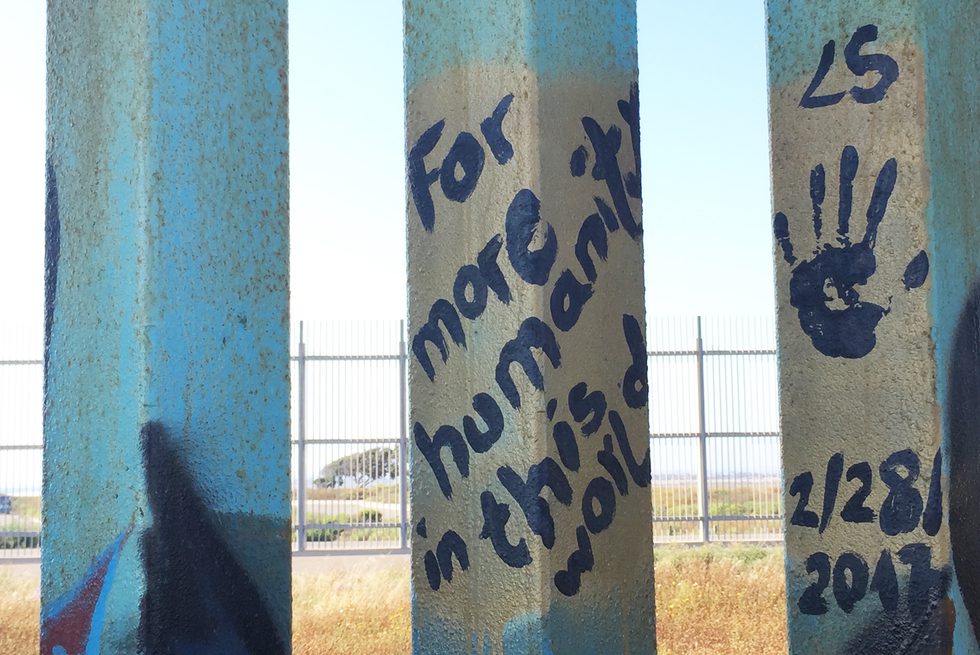

My former student’s explicit recognition that we can be seen and still missed, be visible yet vacated, echoes Ellison’s rendering of things. To see what is otherwise invisible takes a different mode of sight altogether, one that is only possible when the conspiracy of our self-imposed blindness is courageously exposed, in this instance, by expanding our definition of humanity, our understanding of human potentiality—with inspiring implications for the practice of anthropology itself. That’s some of what Pandian has provided in his supple paean.

I see you, Anand Pandian. I see you. And I think you see me, too.

Ellison, Ralph. 1995. Invisible Man. New York: Vintage International Books. Originally published in 1952.