The Joyful Materiality of Pink & Green, and Blue

From the Series: Art and Ethnographic Forms in Dark Times

From the Series: Art and Ethnographic Forms in Dark Times

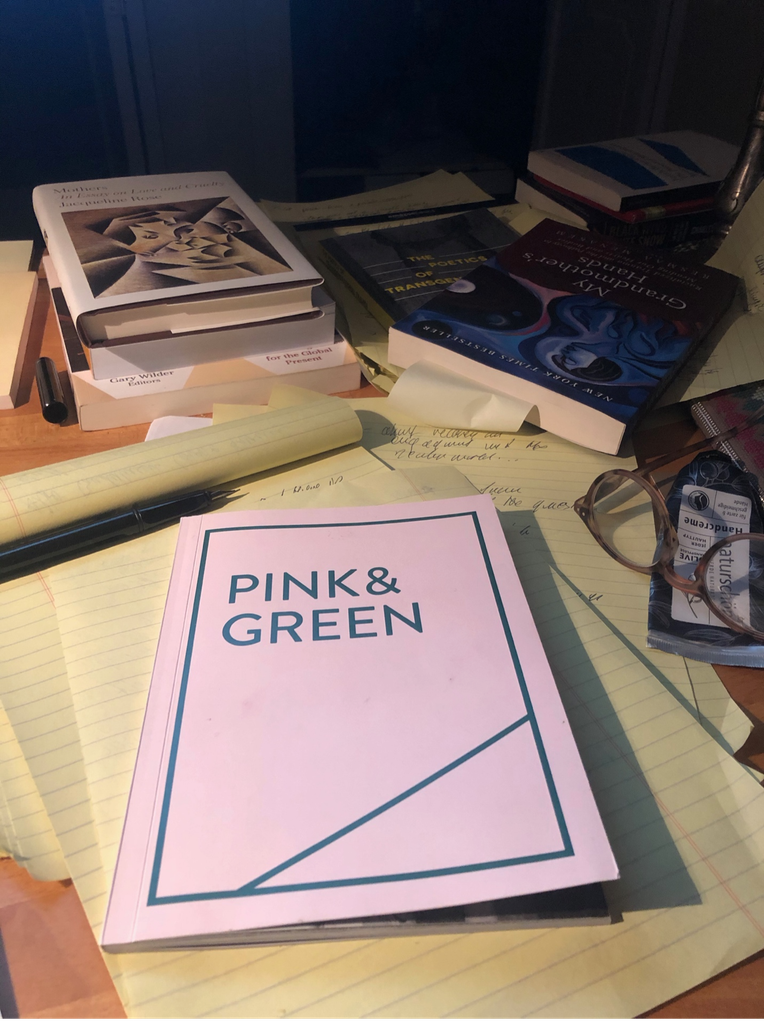

In May 2017 in Toronto, eleven collaborators and I produced Pink & Green, an art zine. For three consecutive days, we met at Artscape Young Place to look at, discuss, and write about zines and other small-press publications. We had come together for different reasons. Some of us wanted to learn more about how to write about contemporary art, others wanted to move away from canonical art writing, and two of my collaborators felt depressed because they worked at a publishing magazine that had started to advocate increasingly for restrictive forms of writing. I was there because I love the experimentalism of many small-press publications and zines, and because I wanted to collaborate with those who shared that excitement and love.

At the time we met in Toronto, I was nearing the end of a five-year commitment as department chair. In those years I had done much administrative thinking and writing, and had participated in seminars on how to brand anthropology as a set of marketable skills. The burden to rationalize and justify anthropological studies on various administrative grounds had begun to feel heavy. I was afraid of losing my sense of joy of teaching and writing. And I did not want to feel resentful and bitter. I had witnessed such trajectories too often.

Initially I found it hard to admit—to my collaborators, to myself—that I was looking for pleasure and joy through my engagement with Pink & Green. In earlier points of my career, pleasure and joy had not been flashpoints for consideration. Premium, then—as often now—was put on critique. This usually meant that the task of the anthropologist was to note social problems, decipher their underlying power relations, and demonstrate the harm of which they are a symptom. Of course, as a number of beautifully written ethnographies have shown, aesthetic pleasure has often been an unacknowledged motive of analysis and critique. Yet anthropology’s critical orientation had also helped to create the conditions that have forced the aesthetic—not unlike many zines (Duncombe 1997)—to operate underground.

Building on collaborative writing practices and mutual discussions, in the end Pink & Green featured eclectic contributions. There were reviews of love songs to Antarctica, meditations on drugs and feelings, recommendations on how to approach paranormal activities, examinations of queer objects, and fictive letters to art school students. I wrote a contemplation on the color blue inspired by a thick, blue velvet curtain that hung in the room where we met. I was smitten with the curtain’s radiance and texture. I wrote:

The velvet curtain that surrounds the small stage in room 101 is saturated in dark blue. Illuminated by electric bulbs attached to the bottom of the stage, it radiates excess, fantasy, and pleasure. Dramatic and stylish, it suggests a swirling mélange like in the paintings of Boyarina Morozova (1886) by Vasily Surikov or Fantasy (1925) by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. It has the iridescent beauty of . . . the blue flower of Novalis that crops up in Walter Benjamin’s writings on aura and art, or the velvet seats in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Wrapped up in the vibrancy of fabric, these associations are tied together by an experience of enchantment . . . of enigmatic and intense pleasure.

At times, the excitement and joy that I experienced through this collective work felt overwhelming. It was inspired by sharing time and space with my collaborators, by being, thinking, and writing together. It arose from the possibility of perceiving or contemplating an everyday object or thing, as it were, when contemplation did not attach itself to its usefulness or purpose. It arose from the recognition that art and aesthetics are constituent elements of life. Not because they narrowly connect to Kantian categories of beauty or the sublime, but because they point out the pleasure and joy that attaches itself to the riotous, irreverent, sprawling, vernacular, ubiquitous, and cheap. I continued:

Most of the art books, zines, and other kinds of objects displayed on tables and chairs are not blue, although I bought a crazily blue shirt produced by Millie Chen for the Koffler gallery. But like the dark blue of the velvet curtain in room 101, they radiate visceral richness, beckoning one to look, ask questions, feel and touch. Presence more than sign, force rather than code: they suck viewers in, sweep them up, and spirit them away. There is freedom and joy, and a sense of possibility: of an aesthetic and political otherwise that dares to dream. Not always already the blue of a literary blues, but an experience of delight and surrender that offers itself up as a release from the dry-as-dust drudgery of conventional writing protocols and their manifold concessions.

I’ve said above that initially I found it hard to contemplate this piece because I found it difficult to admit to others and myself that I was in need of joy. Another reason why I found it challenging to write was because I felt ashamed to put that joy out in public. In large parts of the academy, including anthropology, joy, aesthetics, and art are often looked at with a great deal of suspicion. Like many, I am deeply aware of the usual objections: art, including small-press objects, marks luxury items, often enjoyed only by those in positions of privilege. Art is bourgeois, and serves as a marker of cultural capital and class distinctions. Art provides merely formal and symbolic, rather than economic or political, solutions to real-world problems. Aesthetics, joy, and art deserve to be regarded with suspicion because they do not automatically lead to considerations of solidarity and even justice. The ultimate litmus test that art, then, must pass is the question of how it can help us to effect social change.

Let me be clear. I, too, am committed to working toward political and economic change that is systemic and far-reaching, rather than simply papering over existent conditions. And, yet, it was my participation in the creation of the Pink & Green art zine that brought hope and joy. Not just because small-press objects are things I love, or because they always already evade critique and branding, but because they encourage the contemplation of collective politics and collaboration that mark a necessary precondition for initiating such change.

Duncombe, Stephen. 1997. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. London: Verso.