The Plume: Movement and Mixture in Subterranean Water Worlds

From the Series: Geological Anthropology

From the Series: Geological Anthropology

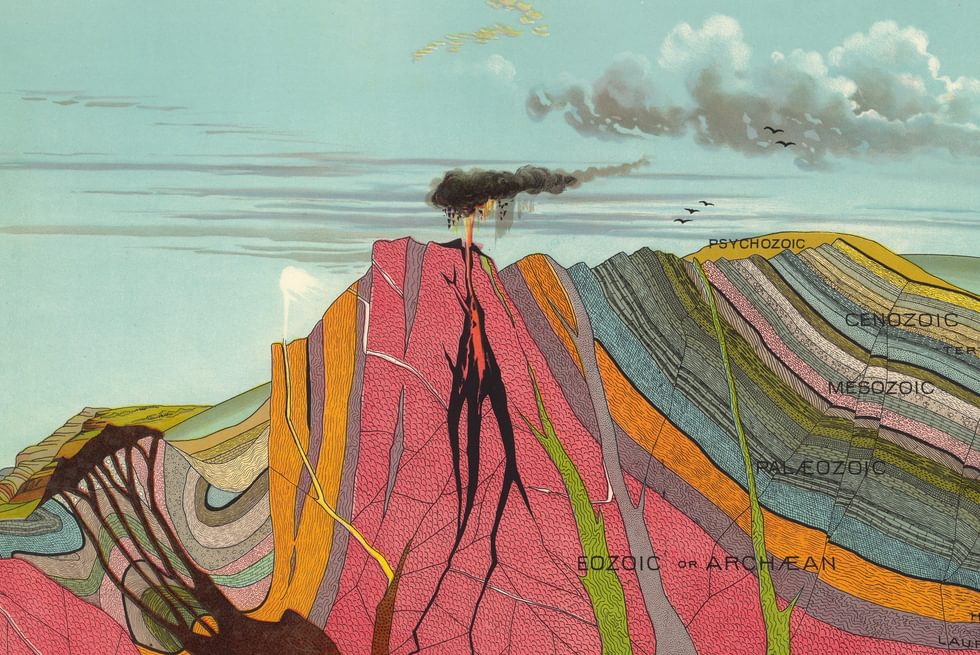

Asking questions about life in science, Kathryn Yusoff (2018) turns to geology and diagnoses it as a field built on the partition between live/inert, human/inhuman. Yusoff qualifies this geology as “white geology,” a scientific domain and praxis built on the impetus to extract inert minerals from the subsurface and a concomitant “category of blackness” built on the idea of the inhuman. Yusoff (2018, 12) makes this geological diagnostic to inspire “a different economy of description that might give rise to a less deadly understanding of materiality.”

Geological anthropology is a powerful means to explore what such different descriptive economy could be like. To that end, I have proposed “recuperating [those conceptual resources that] have been discarded” (Ballestero 2019a, 24) because of their harmful implications—semiotic and material. In this short piece I recuperate the pollution plume as a figure that is quickly discarded as deadly, lifeless, harmful. Narrowly defined, a plume is “a visible or measurable discharge of a contaminant that is released from a particular source into the air, groundwater, or surface water” (Park and Allaby 2013). And yet, when conceptually recuperated, pollution plumes are dramatic figures that challenge any fixity and demand an attunement toward form shifting. Plumes are flow within flow and as such require a radically different understanding of the subsurface that goes past the stratigraphic fixity of white geology. The subterranean plumes I propose are kin to what Jerry Zee (this series) refers to as the opportunities that open up when “earthly materiality is taken as shape—and phase—shifting rather than fixating on fixed and contained forms.” Thinking of plumes through the language of fluid dynamics is an early step toward a geological anthropology that remains committed to new descriptive parameters. Ultimately, a new descriptive economy could allow us to design new matrices of responsibility.

In the past decade, as is the case elsewhere, Costa Rican “spongy aquifers” have risen to a prominent position as geopolitical tokens. The conventional understanding of aquifers as underground tanks or containers is giving way to a more accurate sense of dynamic seeping and oozing in spongy choreographies that challenge the fixity of borders. This changing sense of their form has motivated the use of remote sensing technologies that challenge ideas of touch, distance, and light in mapping practices (Ballestero 2019b). In the midst of this, there are also attempts to reinscribe the subsurface in extractivist schemes. One of those aims to remove an existing moratorium on oil exploration and gold and metallic mining. In this context, aquifers are a new planetary frontier where nature, economy, and the social are interrogated. And yet, despite this prominence, aquifers remain unruly figures that confound our capacity to distinguish between figure and ground (Ballestero 2019c). This is particularly the case when chemical substances seep into the ground, creating concentrations that demand scientific, legal, and engineering responses. Grasping these concentrations is often a practice of rendering knowable the form and movement of a plume.

As described in scientific and technical reports, plumes have form, size, and speed all determined by type of contaminant, solubility, and density, and by the velocity of groundwater movement. Certain contaminants make themselves one with groundwater. Other contaminants retain their form, keeping their concentration, as they travel in water affirming their distinct identity, reminding the observers that they will always be mixtures, never solutions. Contamination plumes expand volumetrically as they work out their relation to their host, the aquifer. The plume is a guest that dissolves itself into its host, at different concentrations throughout its elongated figure.

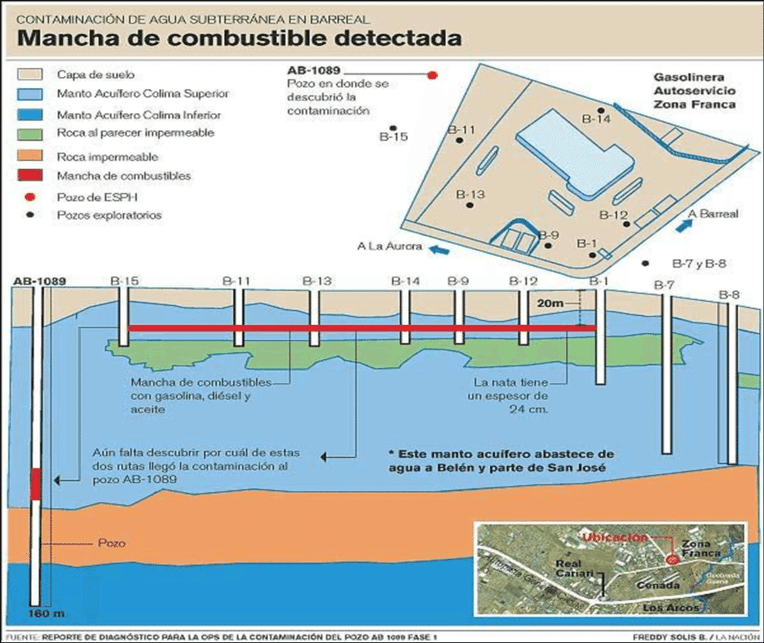

One of Costa Rica’s most prominent plumes, although not necessarily the largest or most toxic one, irrupted in the media in 2004. The municipal utility that provides water to a significant portion of the capital city’s population re-activated a well they had stopped using during the rainy season, as they did every year. When well AB 1089 started operating again, it showed high concentrations of hydrocarbon pollutants. Immediately, a number of agencies got involved and a committee was set up to oversee remediation measures. One of those measures included a legal process with the country’s prosecutor’s office to investigate the source of the contaminants. Investigations confirmed a spill in a gas station in the immediate vicinity of the well. Between 2003 and 2004, thirty thousand liters of gasoline had flowed into the aquifer forming a plume of hydrocarbons. By 2010, through different remediation measures, public agencies “recuperated” thirteen thousand liters of contaminants. However, seventeen thousand liters remained under the surface in the aquifer. Using activated charcoal they filtered more than 1,300 cubic meters of water that were re-injected into the subsurface. These remediation efforts were partially effective, even if seventeen thousand liters of pollutants remained distributed throughout the aquifer in different concentrations. In 2015 courts found the gas station legally responsible for the spill and required it to pay the expenses public agencies had incurred in to clean up the aquifer.

A plume is movement within movement and is scientifically studied under the rubric of fluid dynamics. In technical language, plumes of contamination in aquifers are described as migrant or stable—another way in which fantasies of national borders shape scientific language. How expansive or contained a plume’s contours are is also a matter of textural relations between the intruding substance and the substances in which it tries to move. If contaminants are light, they remain near the upper levels of the saturated zone of the subsurface. If they are heavy, they descend, sinking until they can no longer migrate, attaching themselves to the pores, cracks, and groves of impermeable rocks. A plume is always gauging its attraction toward other molecules, fluid and solid. This elemental choreography is also determined by the intensity with which new molecules push their way into the aquifer, whether they are propelled by jets rushing out of damaged infrastructures or duet to slow leaks—day after day, month after month. As a body that is never distinct from its substrate, a pollution plume in an aquifer is made sense of through concentration and movement rather than connection or stability.

Plumes are unruly forms that demand thinking through morphological reinvention and relentless change in time. Plumes require mobilizing unconventional forms of accountability, scale, and temporality that do not put messianic or survivalist forms of life at their center. Their liveliness cannot be reduced to nineteenth-century understandings of geology. A geological anthropology of the twenty-first century should not do so either.

And yet, plumes are not solutions. With their assumption of homogenous distribution and symmetric form, solutions imply stability, clarity of form. What I want to accomplish by struggling with plumes is a way to think about changing concentrations, non-symmetrical forms, and slow shape-shifting. Attending to movement within movement, to avoid the ossification of value and responsibility, might allow us to chart new descriptive economies that can handle seventeen thousand liters of contaminants as more than remainders. Because description is itself world-making, hydrogeological plumes can help us grasp dimensions of collective life that might go unattended when we reproduce dominant biological and geological vocabularies around life, value, and matter. Plumes, among other figures of the subsurface, help us bring about a geological anthropology that refuses fixity and stability.

Ballestero, Andrea. 2019a. A Future History of Water. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

———. 2019b. “Touching with Light, or, How Texture Recasts the Sensing of Underground Water.” Science, Technology, and Human Values 44, no. 5: 762–85.

———. 2019c. “Underground as Infrastructure? Figure/Ground Reversals and Dissolution in Sardinal.” In Environment, Infrastructure and Life in the Anthropocene, edited by Kregg Hetherington, 17–44. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Park, Chris S., and Michael Allaby. 2013. A Dictionary of Environment and Conservation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yusoff, Kathryn. 2018. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.