The Repetition of Return

From the Series: Anthropology in a Time of Genocide: On Nakba and Return

From the Series: Anthropology in a Time of Genocide: On Nakba and Return

The following is the first-person narrative of an experience of the 1948 Nakba—as told to me by Um Subhi Abu Ramadan, from Hamama village whom I interviewed in the early 1990s in her home in al-Shati Refugee Camp in Gaza.

As anthropologists and academics, we are supposed to take Um Subhi’s narrative and give or make some conceptual sense of it. But I find myself in the midst of the horrors of this unending genocide, unable to make any sense of it—unable to give it any academic meaning or produce any insights from it. There are too many obvious things that could be said—lethal history repeating itself, the Nakba as a continuing ruinous structure rather than an event. In these times any and all of these “insights” simply appear empty words and pithy aphorisms.

They [1] kept making attacks, we’d go out into the fields and find them there, they’d come and shoot at us, shoot at old people not just young men. The young men would fight back—attack their convoys, they’d come and kill two or three young men. The planes would come and bomb the houses people would flee from the village out to the fields, under the cactus and the olives. We’d stay there all night in the dark and in the morning, start going back home—we wouldn’t dare until there was light. But then the attacks would start again, shooting—people would get killed, the planes would come and bomb again—we’d flee back to the fields under the olives and grape vines. We’d grab the kids and hold them tight and sit. No food no water. The whole village together...

Then after some time people started coming from other places from the direction of Isdud, from Beit Daras, from Zarnuqa from Faluja all fleeing to our village; all of them in the fields, under the olives and fig trees—all of them sitting there with their families…

Then the planes came and started bombing us out in the fields. One day you’re making bread and the next day there’s killing and bombing. We all fled towards the sea. The mukhtar [village headman] comes and says we should all go back towards the village. He puts a white flag on a pole and starts walking towards the trenches where the Jews are and they shoot him. He’s carrying a white shawl on a pole and they shoot him. We surrendered and they shot him.

The Egyptians came, we only benefitted from them when they left Isdud. They started telling us to flee. People started leaving from the sea on small fishing boats. Me and my family we left by donkey—me and my kids, we put the kids in saddlebags on that donkey and we go to Gaza.

My husband had been killed two days before. He was guarding our field of peanuts—we had grapes and that field of peanuts and he and three others went out to guard them—scared that people would take them. As he was coming back along the seashore the Jews saw him and killed him. I had just had my son a week before and my relatives found my husband and brought me his body—carried him back on a camel.

I was young and ignorant with six children, three girls and three boys, I left with my parents and sisters carrying those six kids on that donkey to Gaza. We left everything behind, cheese and clothes and grain and chickens.

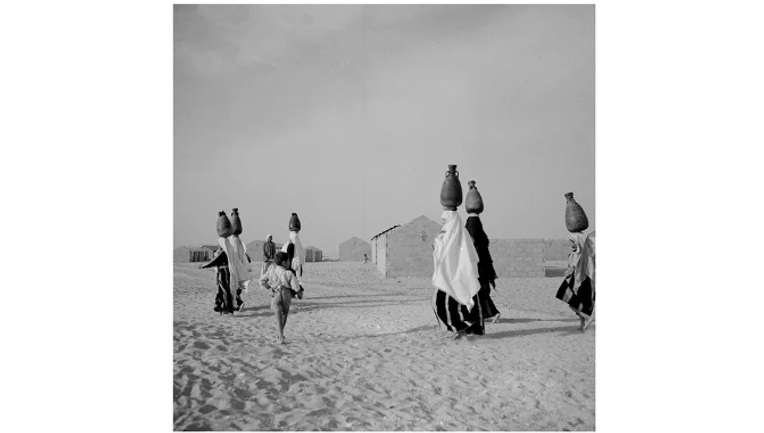

We got to the seashore of Gaza and we were there three days and then the planes came again and started bombing people on the beach, so again we fled, we walked all the way until Khan Yunis because the planes were bombing people. We made a shelter on the beach there in Khan Yunis, with sticks and bags and whatever we could find. Not just us, everyone, every shelter had six families in them each one had their corner. Then they [2] started distributing rations and we’d walk two hours from the beach to Khan Yunis and carry that bag on our head and beg for some wood so we could cook. We’d be making bread and it was raining.

One day I was at the ration station getting the rations and the planes came and started bombing—right into the crowd, people tried to run wherever they could, someone lost their hand, another their leg, people were killed, suddenly there’s a fire and my face and hair is burnt—they thought I was dead—it took me a year to recover.

… We lived on the beach there in Khan Yunis for three years, not just us—all of our village [of Hamama] was there living in there in the dunes. Me and my parents and my children and sisters and brother…

… After some time, they gave us a tent. This was after the shack had collapsed on us from the rain. Inside the shack we slept on the sand and made pillows from guava leaves then when it rained the water would come up through the sand and soak everything. Then it rained so hard the shack collapsed…

Then they started to make the camps [3] and people went north to live in the camps…We came here (to al-Shati camp) because all of our relatives were here.

In my own attempts at sense making of Um Subhi’s words and experience during the enormity of now– the only approach that feels right to me is to imagine Um Subhi’s story and what is happening now—side by side—like two parts of a split screen on television. It’s the only way I could find to try and express—not what the two Nakba’s of 1948 and of these last unrelenting twelve months mean in terms of the never-ending traumatic history of a people—but how the lived experience of Um Subhi, her children and grandchildren, and of Palestinians as a people simply defy our conventional understandings of history and human experience altogether.

Then I reflected back to the time when I did the interview with Um Subhi, back in the early 1990s. Remembering it through the lens of what is happening now—and that led me to a realization that I couldn’t have made back then. Um Subhi narrated to me her experience of the Nakba as episodes of loss, suffering and injustice but she also did so with a subtle, but unmistakable, stance of pride and self-assertion connected to the intertwined story of what I will call, her and her family’s “return” from that first Nakba. Of how a destitute, illiterate widowed mother of six, against all odds, rebuilt and remade life and returned the possibility of happiness and a thriving future to herself and her children in Gaza.

That story of Um Subhi’s return is only one of countless more: refugees who through force of will, creativity and hard labor in Gaza (and elsewhere) who returned their shattered society of 1948 from a state of genocide and death, back to life and a state of becoming—resurrecting from the ashes myriad vital and dynamic Palestinian life worlds, futures, and possibilities.

That is the supreme parallel between 1948 and now, that for me makes sense and that I want to hold on to. History may have defied us—but as people in Gaza show us every single day, we Palestinians defy history.

[1] “They” here refers to the Zionist forces, specifically, the Haganah.

[2] “They” here refers to the Quakers and International Red Cross who were the humanitarian agencies operating in the first year of the Nakba in Gaza until the creation of UNRWA in late 1949.

[3] Al-Shati camp was established in late 1949.