The Terruco Problem

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

This is an addendum to a previous thought in light of Peru’s descent into crisis following the ousting—also self-sabotage and political trap—of Pedro Castillo and what followed: a pact between Dina Boluarte and a repudiated Congress to protect the status quo using state violence against a popular uprising that demands political participation (immediate elections and a new constitution) and not a state takeover. The mobilizations emanate largely from Peru’s southern Andean provinces. Really, this is just the latest irruption of Peru’s “irresolvable” problems along axes of class, race, geography, worldview, and others.

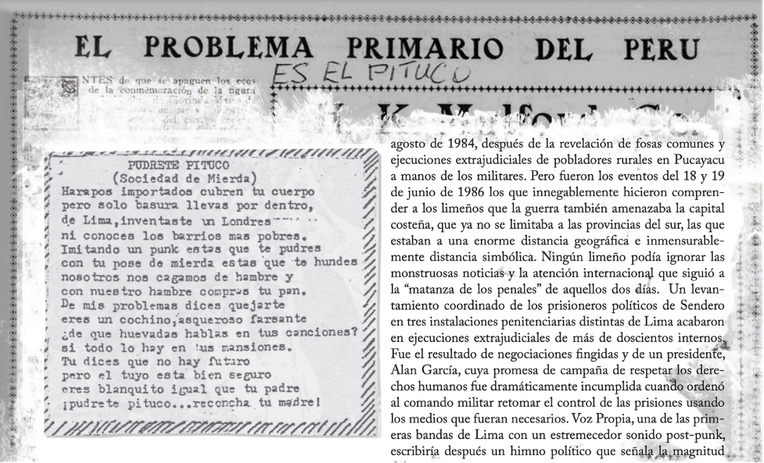

In 2014, I self-published a fanzine titled “El problema primario del perú es el pituco,” plastering thoughts and images atop José Carlos Mariátegui’s 1924 article naming the indio (Indian) as Peru’s main problem (Figure 1). It reappeared in a book arguing Lima’s 1980s punk scene emerged within the logics of Peru’s war, which left a Maoist insurgency (Shining Path) in a state of exaggerated demonization. As one of Latin America’s most famous Marxists, Mariátegui analyzed the Indian problem as rooted in colonial dispossession of land and relegation of Andeans to servitude. Anibal Quijano later rearticulated this on a more global scale as the “coloniality of power” (Quijano 2000), featuring race more prominently than Mariátegui ever did.

My desire was simple. Inspired by the band Sociedad de Mierda’s (SdM) song “Púdrete pituco” (“Rot pituco”), I presented a provocative if not necessarily radical idea. In reference to a conflict in the punk scene along cholo (urbanized, migrant Andean) and pituco lines, a microcosm of the war itself, I suggested we flip the script. Let’s give a different but equally specific name—pituco—to Peru’s problems of historical injustice.

Pituco means all of the following: rich, socially ascendent, living in posh neighborhoods, white or whitish, dressed well, snobbish, showing familiarity with English. The list is endless. It’s also a general condition, pituquería, and a reflexive verb, pituquearse, to become a pituco.

All I meant is pituco = top-down power and prestige. It’s a Peruvian way to talk about who has it, who defends it, who benefits from it. When the initial right-wing protests against Castillo’s campaign began, I was taken with just how out, proud, and pituco the reaction became. Some saw resonances with the U.S. alt-right. I saw pituquería in action. Curiously, anti-Castillo Peruvians began openly declaring themselves pitucos. It was part theater of the absurd—a blonde woman on TikTok claimed P.I.T.U.C.O.S. is an acronym for Peruanos Independientes Todos Unidos Contra la Opresión Socialista (Independent Peruvians All United Against Socialist Oppression)—and part online trend. This is significant because the point was, historically speaking, no one willingly assumes pituquería. Pituco is one of those ascribed insults, issued by someone claiming distance from power or prestige.

I now realize I never connected pituco to terruco. Terruco is slang for “terrorist.” In its circumscribed sense it is an accusation of affiliation with the Shining Path. But it has taken on more generalized meanings as part of right-wing and “market-solves-everything” hegemony, a product of Peru’s war with U.S. anti-communist paranoia attached (Rodríguez-Ulloa 2021). Terruco has become the term Peruvians seeking to defend power, and reassert everyday coloniality, deploy to dismiss any form of dissent: from the poor, feminists, environmentalists, Indigenous people, university students, random people on the street. It defines the present.

As the right “exposed” Castillo for the clumsy Marxist rhetoric of his political party, usage of terruco permeated anti-Castillo sentiment. The word is deployed not just against his allies but anyone supporting the basic idea that an Andean school teacher advocating for the poor has a right to executive power. It circulates with “motoso,” a racial insult meaning “Indian who can’t speak” (i.e., has corn in their mouth, mote meaning corn) and should therefore stay silent in public and politics.

On January 19, 2023 I watched the Instagram feeds of @Wayka.pe and @juventud_anarquista_lima, as Lima’s streets filled with Andeans who came in caravans from the provinces seeking urban allies and were met with tear gas and a political elite digging its heels in deeper with every public announcement. For every expression of support, internet trolls retorted: “terruco de mierda,” “malditos terrucos,” “terrucos de mierda, vayan a trabajar” (fucking terrorist, goddamn terrorists, fucking terrorist go back to work).

Less disheartening, a Peruvian judge recently issued a sentence against a right-wing newscaster in a defamation case brought by Anahí Durand, Castillo’s former Minister of Women. It sets the first precedent in Peruvian legislation against “terruqueo,” the practice of slander with empty accusations of “terrorism.”

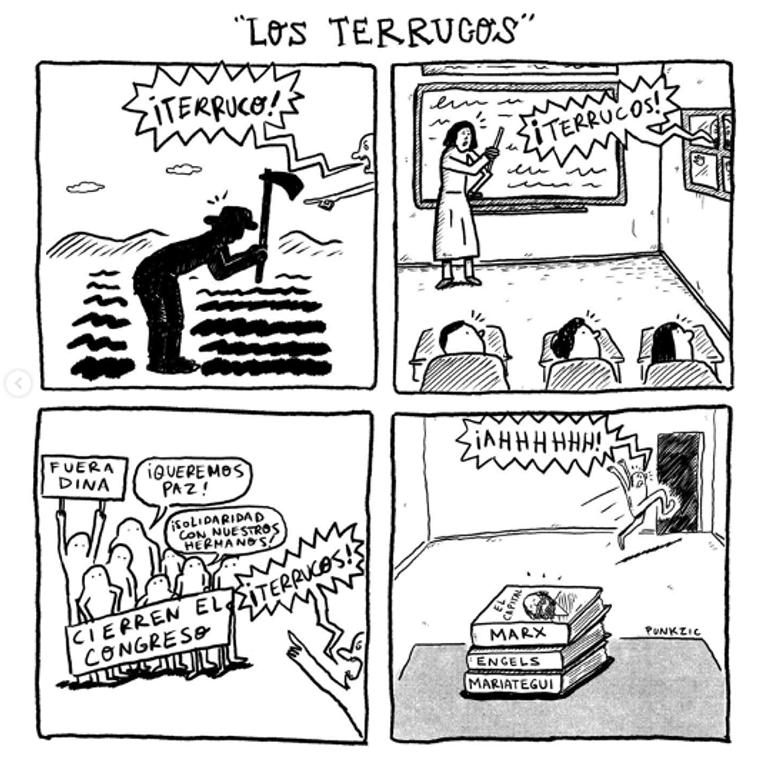

I’ll close with a comic to circle back to the subcultural politics that started this reflection. The day before the march on Lima, an online illustrator named @punkzic posted a series of illustrations. A farmer, a teacher, and protestors appear as a random subject ruptures the frame and screams “terruco!” It ends with a close up of books (Marx, Engels, Mariátegui) as the subject runs away in horror at his ignorance of what socialism even means (Figure 2). The illustrator was labelled terruco within the first three comments on the post.

The problem of Peru’s moment is deep, but it’s also immediate, caused by reactionaries who see terrucos everywhere they go. The Peruvians now demanding a political participation they are still denied are enacting a different kind of power, dispersed and emanating from below, in the streets, from the public university, on the mountainside, in the underground.

Let’s call it cholo power. And recognize there’s nothing more likely to provoke such reactionary ire than the cholo who refuses further servitude.

If you can’t see that, you’re just a fucking pituco.

Quijano, Anibal. 2000. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3: 533–580.

Rodríguez-Ulloa, Olga. 2021. “Sadistic Cholas: Sex and Violence in Punk Literature” In Punk! Las Americas Edition, edited by Olga Rodríguez-Ulloa, Rodrigo Quijano, and Shae Greene, 177–195. Bristol, U.K.: Intellect Ltd.