The Whiteness of DACA

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a conditional form of temporary work authorization and deferment from deportation for im/migrants who arrived in the United States as children, is often mischaracterized as the Obama administration’s cornerstone immigration “achievement.”1 Eliminating DACA was a priority for the Trump administration, which viewed its termination as central to advancing Trump’s racist and xenophobic agenda. A decade after the program’s original implementation, and just some months out from its reinstatement by the Biden administration, an analysis of this policy at the level of structure is long past due. Informed by ongoing conversations with abolitionists who organize and struggle for a world without prisons and borders, as well as personal experience undergoing nine years of surveillance as an illegalized person with DACA status, my argument echoes what many of us already know: DACA is a policing technology, first and foremost. Black-led uprisings and organizing against endemic police violence have ushered in a new abolitionist era. In this context, DACA and policies like it represent an expansion of the police state. They run counter to the goal of long-lasting protections for im/migrants and grow the prison industrial-complex, which includes the machinations of detention and deportation.

My assertion does not aim to dismiss the damage wrought in our lives and communities due to DACA’s rescission under Trump. Without erasing the impact of organizers who fought for deportation protections for illegalized young people, it is necessary to fully problematize how DACA has contributed to the colonial myth of the criminal alien, as well as how it continues to conscript migrants into the service of American empire. DACA does not combat illegalization, or the very making of “the illegal.” DACA reifies illegality. The program entrenches young migrants’ criminality by codifying border crossing at any age as a grave transgression that warrants indefinite surveillance. DACA recipients often find themselves closer to the grip of carceral systems, as this is the price of precarious and conditional “protection.” Through the program’s collection of personal information and close inspection of criminal history, the tentacles of federal and local law enforcement collude to ensure DACA recipients are on the state’s radar.

DACA is a white technology because it is a policing technology. I refer to the whiteness of policing following the teachings of scholars and organizers like Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2007), Nikhil Pal Singh (2014), Marisol LeBrón (2019), Kelly Lytle Hernández (2017), and Dylan Rodríguez (2020). With others, they are in dialogue about the historical role of policing in slaveholding and settler societies, which represent the ongoing enforcement of a capitalist/colonial white supremacist racial order underpinned by anti-Black and anti-Indigenous relations. These arrangements do not only take shape domestically but also internationally in the form of imperialist policy. This theorization of policing goes further than any moral claim about the individual actions of police officers, or even police institutions. Instead, as one persuasive articulation by LeBrón (2019) suggests, policing is structure. While there are individual Black and Indigenous DACA beneficiaries, DACA guidelines follow the same colonial logics that are employed to carry out the American carceral and settler project. Shifting the focus away from the individual accomplishments of a small group of illegalized migrants to this structural context brings into question even the policy’s short-term success.

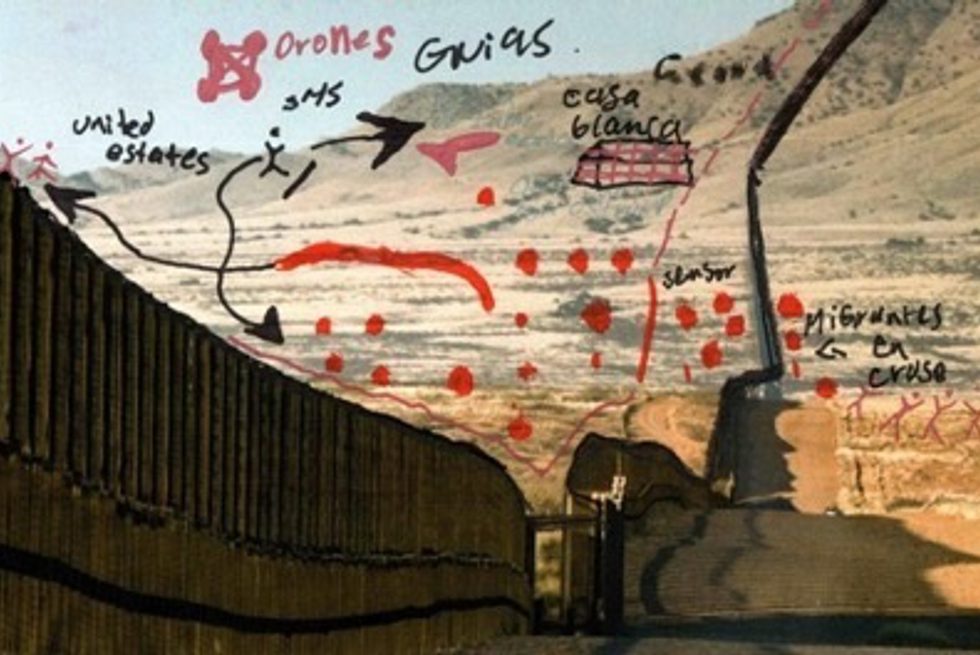

Social scientists have dubbed DACA “the most successful policy of immigrant integration” of the past decades, but this essay points to the ugly underside of integration. Recipients are bargaining chips in negotiations over immigration enforcement where they are simultaneously criminalized and used to criminalize more vulnerable migrants. While some movements for im/migrant rights recognize the pitfalls of the “good vs. bad immigrant” narrative and call to #AbolishICE, political deals continue to tie DACA protections to increased border militarization targeting asylees and refugees. DACA functions domestically through the criminalization of its recipients and internationally through imperialist policy.

Fighting for “protection” under DACA is a strategy of recognition and inclusion, rather than an abolitionist endeavor that rejects the state’s active role in upholding illegalization (Rubio and Alvarez Almendariz 2019). To put it bluntly, that is why DACA beneficiaries cannot commit crimes that rise above “significant misdemeanors,” legally own guns, or carry any amount of marijuana, even in states where the drug is decriminalized or legalized. DACA recipients are also subject to the illegalization of poverty because we are always just $495 away from falling out of status.

Yet nowhere is the whiteness of DACA most evident to me than in the disembodied experience of undergoing biometrics. My body always feels launched into the process without consent—I am made and remade illegal. In this context, it feels like a betrayal of my bodily and spiritual sovereignty to give up my fingerprints, to lie about my gender, and to disclose my current address so “they” can come knocking on my mother’s door when they deem necessary. I already imagine some readers may be thinking, Don’t worry about that, you’re a good immigrant. I recount all the “crimes” I have committed against this country, sitting in the immigration office lobby. I think about all the crimes committed in my lineage that led me here. I find some humor in knowing I will be hardly recognizable in a few months; another gift of refusal that testosterone gives me.

1. The Obama administration announced DACA protections via executive order only after immense pressure from immigrant rights activists led by illegalized youth.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hernández, Kelly Lytle. 2017. City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771–1965. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

LeBrón, Marisol. 2019. Policing Life and Death: Race, Violence, and Resistance in Puerto Rico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rodríguez, Dylan. 2020. White Reconstruction. New York: Fordham University Press.

Rubio, Elizabeth Hanna, and Xitlalli Alvarez Almendariz. 2019. “Refusing ‘Undocumented’: Imagining Survival Beyond the Gift of Papers.” Member Voices, Fieldsights, January 17.

Singh, Nikhil Pal. 2014. “The Whiteness of Police.” American Quarterly 66, no. 4: 1091–99.