Twelve Hours of Tension: Re-Collecting Fordham’s Prematurely-Scattered Gaza Encampment

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

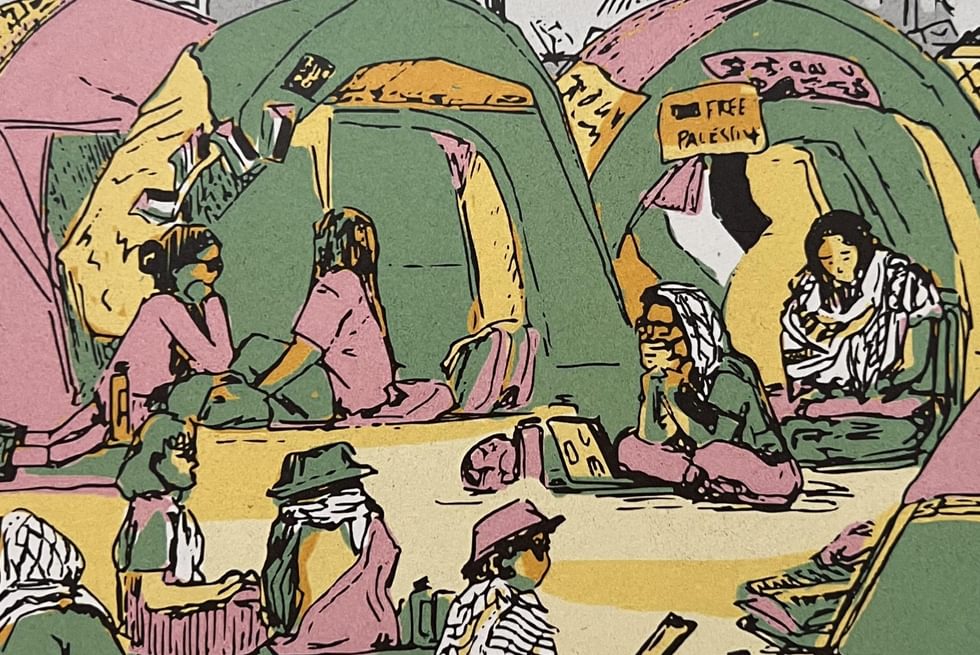

Fordham University joined the fray of colleges across the world in solidarity with the Palestinians affected by the genocide in Gaza on May 1, 2024. Our encampment ran from 6 AM until 6 PM, one of the shortest in the United States. Months following the action, a faculty member and five students, including Manon McCollum and Kenny Moll, came together for a roundtable discussion to recall the events within those twelve hours. This contribution will relay some of the students’ discussions in the roundtable and written reflections on the demonstration. This piece will briefly analyze the themes of translation, tension, solidarity, and merging identities experienced by the camp participants. We replace the students' names with the letters A and J for anonymity.

“During the encampment, I was in the position of being given the news of our new ‘threat and risk level’ from the administration, and then delivering that to the other students,” recalls J, who had been involved in organizing the encampment from the beginning. “I think that is where my internal conflict about [my role] rests: in those moments of like, ‘okay, so I've just received this information, and my goal is preserving the encampment which is making material disruption.’ With that at the front of my mind, ‘how do I then deliver this news in a way to the students and the people at the encampment that’s respectful of their levels of comfort and privilege, while also framing it in a way that’s like, “stay!”?’—for lack of better words.”

– Edited roundtable interview with J, August 16, 2024.

J, through the depth and duality of her commitment to the protesters and the movement, as well as her agility in recognizing their fleeting and fragmentary intersections, maneuvered this translation-in-tension. The same cops who had come from brutalizing the CCNY and Columbia protesters less than five hours earlier were now encircling J and her fellow encampment leaders, fully clad in riot gear, quickly closing off one exit after another to the midtown campus’s main lobby. First the escalators descending into the lobby and the entrance ways, then the ascending escalators out of the lobby and the exit doors. Then the hallways. The staircases. The fire doors. The circle of cops closed in, choking off the encampment.

With each preceding movement, administrators approached J with a new offer. We’re on your side, they told her. We just want to get you out of this quickly so we can negotiate your requests. J wasn’t going anywhere, quietly strategizing how she would steel her comrades, many of whom she had only met earlier that morning.

“By the fourth hour of the encampment it was impossible to ignore what was happening in the lobby. The sun illuminated our Palestinian flags, posters, and symbols of resistance for all passing by to see. The crowd accumulating outside grew exponentially as time passed. Fordham could no longer be silent to our efforts, I thought; they could not ignore an action this provocative. I was surprised when Fordham maintenance workers were instructed to throw a tarp over our Palestinian imagery—not because of our university’s refusal to address issues that clearly concern their students, but because of how brazenly it was willing to act to suppress these students. I suppose this was a sign of what would come later in the day. The encampment closed in on its fifth hour, as did four and a half dozen police officers, encircling the lobby in layers: eight inside, twenty surrounding the doors, another twenty-five in another circle around them. Escape was becoming more elusive as they blockaded the escalators, stairs, hallways, entrances. I hadn’t even had breakfast yet, and probably for the best. I felt trapped and suffocated. I began to feel disoriented, light-headed and vision-clouded. I squinted to look outside where over two-hundred students were now organizing their own impromptu protest in support of the camp. The solidarity overwhelmed, almost replacing the oxygen deprivation and momentarily subduing the panic. But I couldn’t risk arrest like the others. I could barely scrape together enough to pay rent, and if I lost my scholarship, I would end up with permanently-crippling debt in a matter of hours… I couldn’t tell if I was choking on panic or the stale air from the greenhouse effect of the afternoon sun burning through the lobby’s massive glass windows, considering the many hours now since the facilities manager had shut down the air conditioning and HVAC circulation system.”

– Written correspondence from A, August 17, 2024.

“In the encampment, our physical bodies, masked and as unidentifiable as we could make them, represented a small, albeit important, part of a larger movement. The longer we spent in the encampment, the more I felt as if my physical body and my identity itself no longer belonged to me; as if I was being pulled in two ways. In one direction, my identity belonged to the movement, belonged to the community in service of people power. In the other, my identity and body belonged to the opposition in all its forms: to the media who would use our images and likeness to portray these protests as violent or ‘antisemitic’; to the university and administration who would attempt to sweat us out, send in cops in riot gear to arrest us, and physically take us away; and to the police, who would mangle our arms behind our backs, shove us into a van and then into a holding cell for hours on end.”

– Written correspondence from Kenny Moll, August 17, 2024.

We also referenced the themes relating to this malleable and controllable body Kenny discussed in our discussions of identity during the roundtable. While answering a question on differentiating identity in the encampment, J responded,

“When I led chants, a number of them were Arabic chants. I think it has a lot to do with being in this movement for Palestinian liberation and a lot of it has to do with developing a relationship to the Palestinian culture and to Arab culture and Muslim culture at large, even if you’re not part of it directly. And I think for me it was quite easy because I grew up around it. I’m not Arab or Muslim, but I definitely grew up around a really big Muslim community and I studied Arabic, so I think it was a little bit easier. But I think that is one part of it, right? We all bring our unique identity to the encampment, but I think there’s also a central identity, right?”

– Edited roundtable interview with J, August 16, 2024.

The central identity J highlights finds familiarity with Kenny’s point on their physical body acting as a contribution to the broader Palestinian movement. More specifically, there seem to be ideas of merging identities in spaces of activism like protests or encampments, which may help one emphasize the people the movement affects. Kenny, a white man, concludes their recollection by saying,

“The choice to remain in the encampment and make a small sacrifice stems from my identity and body being afforded the opportunity to take a stand and not face more intense repercussions. This privilege is directly provided to me through the oppression and exploitation of the very people we chose to fight for. As I talk of my identity, my body and my actions, it’s important to remember the countless identities and bodies that have been oppressed or prosecuted by identities and bodies just like mine.”

– Written correspondence from Kenny Moll, August 17, 2024.

Our recollections of the encampment have provided us with insight to challenge ideas of syncretism in politically active spaces. We look to our experiences in the camp and wonder if we may come to terms with our dual loyalties for our fellow activists and the broader movement. We grapple with the ideas of exploiting our bodies in these spaces by opposing forces and how fickle our identities remain to maintain solidarity. And yet, we understand the value of solidarity and how it may push us to remain ardent for Palestinian liberation.