This post builds on the research article “Viral Clouds: Becoming H5N1 in Indonesia,” which was published in the November 2010 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published a number of essays on social and political crisis in Indonesia. See, for example, Karen Strassler's “The Face of Money: Currency, Crisis, and Remediation in Post-Suharto Indonesia” (2009), Nil Bubandt's “From the Enemy's Point of View: Violence, Empathy, and the Ethnography of Fakes”(2009), and Webb Keane's “Knowing One's Place: National Language and the Idea of the Local in Eastern Indonesia” (1997).

Cultural Anthropology has also published essays on emerging forms and discourses of security, including Andrew Lakoff's “The Generic Biothreat, or, How We Became Unprepared” (2008), Joseph Masco's “Survival is Your Business": Engineering Ruins and Affect in Nuclear America” (2008), and Sherene Razack's “From the "Clean Snows of Petawawa": The Violence of Canadian Peacekeepers in Somalia” (2000).

Additional Works by the Author

Celia Lowe is the author of Wild Profusion: Biodiversity Conservation in an Indonesian Archipelago (Princton: Princeton University Press, 2006) and "Making the Monkey: The Rise, Fall, and Re-Emergence of 'M. togeanus' in Indonesians' Conservation Biology" (Cultural Anthropology 19.4(2004):491-516). She has also published other articles, including "Recognizing Scholarly Subjects: Collaboration, Area Studies, and the Politics of Nature,” in Knowing Southeast Asian Subjects (Laurie Sears, ed., 2004), "The Potential of People: An Interview with Chayan Vaddhanaphuti" in Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, special issue "Intellectuals and New Social Movements Vol II." 12(1), and "The Magic of Place: Sama at Sea, on Land, in Sulawesi, Indonesia" in Bijdragen tot de Taal, Land, und Volkenkunde. 159(1):109-133.

Questions for Classroom Discussion

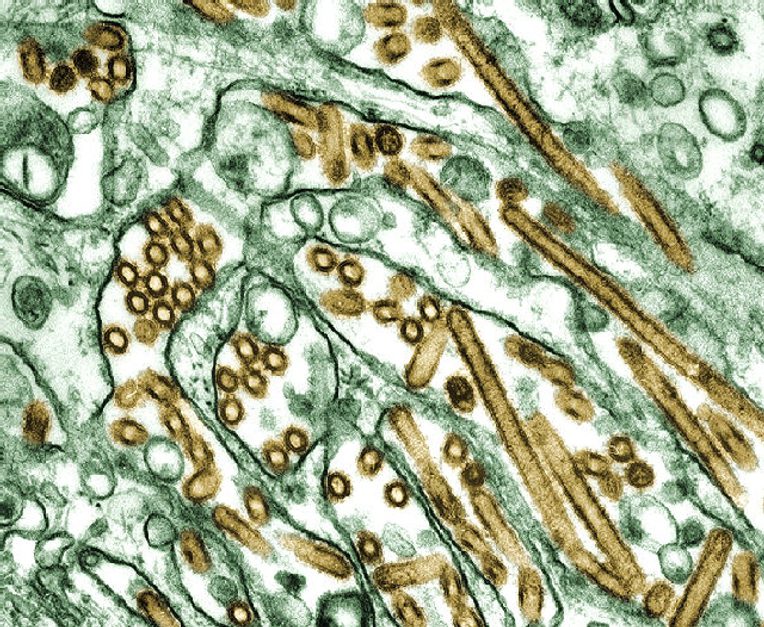

1. Why are RNA viruses difficult to separate and categorize neatly into species?

2. What does Lowe mean by her claim that the avian flu virus is a species multiplier?

3. How does the quasi-species cloud generate biosocialities, species and narratives?

4. What makes Indonesia's biosecurity practice and discourse an exception to Lakoff's notion of "vital security"? Can you think of other regions or countries where the notion of the viral cloud might raise interesting insights?

5. During the height of the Avian flu scare, images of cockfighting or backyard poultry production became associated with "Asian culture" which were blamed for spreading the H5N1 virus. How do the H5N1 virus interventions obscure structures of neoliberal agribusiness governmentality? See, for example: “Bird flu crisis Small farms are the solution not the problem”.

6. Why are politics of scale importantly particularly in figuring Indonesia's relationship to the H5N1 disease?

Editorial Overview

In "Viral Clouds:Becoming H5N1 in Indonesia," anthropologist Celia Lowe tracks the concept of biosecurity through her fieldwork in Indonesia, and observes that security thinking in Indonesia does not follow the security design of US public health and national security establishments in guarding “vital infrastructures and current political-economic arrangements”; but was rather more concerned with the “normative rationality of population”. Between 2005-2006, Indonesia catapulted on the world stage as the country with the highest number of human deaths from the H5N1 virus; and soon became the target of global health measures such as massive poultry culls and security checks which were rationalized by global narratives as necessary for the protection and health of other peoples and nations. Following the RNA virus ethnographically in Indonesia by talking to local bird owners and workers in private international security firms operating in Jarkarta, Lowe makes the argument that the RNA virus H5N1 acted as a “species multiplier” in the way it interacted with other ontologies, histories, institutions and communities. In leveraging and building upon the metaphor of “the cloud” as it “operates through infections, reassortments that are coincidental, responsive, opportunistic, and often non-rational”, Lowe proposes alternatives to the metaphor of the “global assemblage” which has so far provided very powerful explanations for processes of global exchange. A powerful and ethnographic intervention into the debate surrounding global exchanges, "Viral Clouds: Becoming H5N1 in Indonesia" clearly conveys the possibility that “the past and present are tied to but do not contain the future for either humans or influenza viruses.”