In early February 2020, three days after the first Covid-19 case was detected in India, a message went viral on social media. “BOILER CHICKEN HAS BEEN FOUND TO HAVE KORONA VIRUS,” it read, “AN APPEAL TO EVERYONE TO STOP USING BOILER MEAT.” A sallow broiler chicken, beak agape and eyes shut, appeared gasping for its last breath of air. More visceral were the images of entrails and clotted blood. The message conjured a sickening sense that Covid-19 was at India’s doorsteps and in our food. When variations of the chicken meme implicated Dalit and Muslim communities, India’s marginalized were brought to the center of concern.

Poultry and egg consumption suddenly declined as the message proliferated through the Indian WhatsApp network, before spreading far and wide via Facebook and Twitter. By mid-February, sales dropped by 50 percent and broiler prices crashed by 70 percent, well below production costs. Virtual virulence actualized worlds. A farmer from Karnataka filmed himself burying a truckload of six thousand live birds to cut losses. The video went viral, sparking culling episodes elsewhere. “Rumors, rather than the coronavirus, are taking lives,” Durlav, a poultry farmer from Assam, tells me.

Online forensics suggest that the chickens were not “sentinels” signaling a pandemic to come (Keck 2020), but rather misinformation machines. The ailing chicken images were copied and pasted from a website describing Aspergillosis and a research paper on Colibacillosis, conditions unrelated to Covid-19. Microblogging has spurred an “infodemic” in India. Deliberately fabricated news—as intensities put to reactionary ends—is fostering a molecular fascism, where hostility proliferates virtually via a band of trolls, anonymous users and fictitious accounts, and incivility mutates through memes and an impulse for “likes.” Was the enrollment of India’s Muslim and Dalit communities in these messages an early attempt to blame them for the pandemic? One cannot say for certain. But by now it is clear that neither the carriers of Covid-19 nor the impacts of virtual contagion are restricted to any one community.

Viral messages are fabricated but real. The fake chicken stories recast commodity fetishism, conjuring a microspectacle of illness and fear aiming to disrupt rather than foster consumption. How extensive might the material and ecological effects of this virtual contagion become for India’s farmers and agricultural sector? Here is an example of how infodemics and pandemics intermesh, with implications for human and more-than-human life.

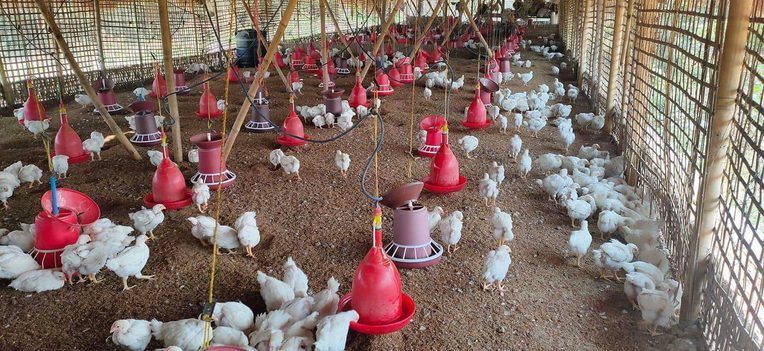

It is still early days, but virtual contagion exposes the vulnerability of poorer farmers to market volatility, vulnerability that is at once structural and metabolic. As the world’s third and fifth largest producer of eggs and chicken, respectively, India’s poultry industry is now incurring losses of US$21 million a day. Share prices of major firms have plummeted due to a decline in effective demand. A striking organizational feature of the industry, however, is that production predominantly relies on backyard farmers locked into precarious contracts with larger, capital-intensive “integration companies.” Contract farmers perform labors of care, raising chicks and selling them back to integration companies at a nominal price as and when the latter need them. Farmers typically rear a single batch at any given time, investing as much as 60–70 percent of their meager capital into the flock. Firms scale up production through integration while minimizing their own risk and retaining control over the sector. Hit by the lack of effective demand, as Kamal, another contract farmer from Assam, said to me, “WhatsApp forwards have brought ruin.”

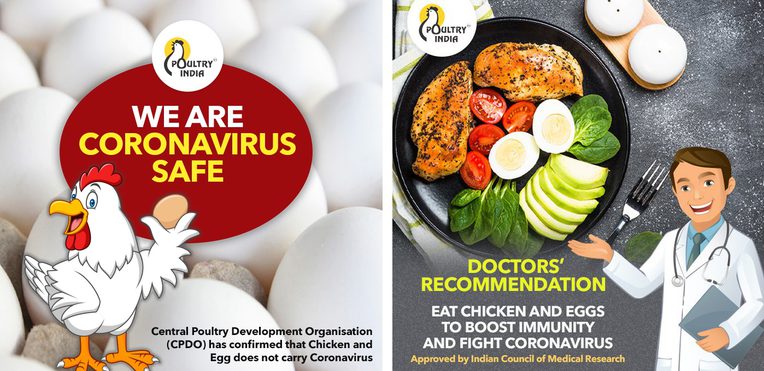

The poultry industry has sought to counter the infodemic by channeling other affects and promoting a biopolitics of immunity. The Indian Council for Medical Research and the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India were mobilized to declare chicken consumption safe. Clarifications were widely circulated, as were anthropomorphized renditions of “happy” chickens telling viewers “WE ARE CORONA VIRUS SAFE.” A further campaign has entailed using the birds to sell immunity through commodity consumption: eating chicken is not only safe, it keeps Covid-19 at bay by building immunity. “Much of this has come a month too late,” says Kamal, reeling from the impacts of microblogging.

Farmers’ predicaments only worsened with interventions to curb Covid-19. On March 24, 2020, the Indian state announced a twenty-one day nationwide lockdown. Everyday life was suspended through recourse to an antique piece of colonial legislation: the Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897. Lockdown quelled democratic protests that had been ongoing for months and triggered a mass exodus of migrant laborers from cities. Lockdown renders visible but also annuls life. With chicken and feed initially classed as nonessential agricultural products, farmers have been unable to obtain feed for broilers. For five days Durlav’s chickens have had nothing but water and paddy husk. Hungry birds come scurrying as he waves an empty sack. “They think I have come to offer feed.” Metabolic lives of people and chicken are intertwined. During pandemic times, forces of dispossession run rife through both. “I have been unable to eat. How can you, when hundreds of birds are starving?”

Lockdown has slowed what Karl Marx (1978 [1885]) famously called the “turnover time” of capital. Besides farmers’ care work, poultry production is contingent upon chickens’ metabolic labour (Barua 2018) and subtending infrastructures including transport and feed. With lockdown, avenues for realizing value are blocked. Affiliated sectors such as the corn and soybean industries are already witnessing price crashes since the poultry industry is their main consumer. Capital-intensive firms have begun “liquidating stock” to cut losses from providing feed. Slaughtered birds are being frozen in cold storage, suspending capital in commodity form, with the hope that biovalue (Sunder Rajan 2006) will be realized in the future. This is too expensive an option for Durlav who, like thousands of contract farmers, started his poultry business with a bank loan. “How am I ever going to pay back?” he asks, “The bank will soon send notice.”

Covid-19 has hit poultry farmers not once, but twice: first as rumor, then as force. Durlav and Kamal have little immunity from the jolts of capital. Their predicament cannot be frozen. From his backyard farm, Durlav contemplates over the horizon beyond the anticipated pandemic. “After coronavirus, after everything improves, if I don’t become a wage laborer toiling in some distant city, I will be unable to feed my family.” His language is corporeal, metabolic. Durlav knows the biopolitics of abandonment only too well. “If our birds die, so will we.” In the meantime, his broilers slowly peck away at empty feeders.

References

Barua, Maan. 2018. “Animal Work: Metabolic, Ecological, Affective.” Theorizing the Contemporary, Fieldsights, July 26.

Keck, Frédéric. 2020. Avian Reservoirs: Virus Hunters and Birdwatchers in Chinese Sentinel Posts. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1978. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume II. Translated by David Fernbach. London: Penguin. Originally published in 1885.

Sunder Rajan, Kaushik. 2006. Biocapital: The Constitution of Postgenomic Life. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.