Ways of Seeing Light in Dark Times with Graphic Ethnography: A Reflection

From the Series: Graphic Ethnography on the Rise

From the Series: Graphic Ethnography on the Rise

Truly, I live in dark times

…he who laughs

has not yet received

the terrible news

—Bertolt Brecht, “To Posterity” (1939)

When I was asked by a journalist in late 2020 how we are to know that we live in dark times, I pointed to alarming statistics that indicate horrific, worldwide, human suffering. When she asked how we are to recognize the darkness, I turned to pages from Light in Dark Times, the graphic ethnography that Charlotte Corden illustrated and that I authored.

Some may not want to see the darkness, but it is there, nevertheless. Those who are spared from the worst of social suffering and from the forces that cause it may fear going to the dark place, to see it and come to know it. Charlotte and I created the graphic book to disrupt denial about the darknesses of the past and the present, to affirm what I believe many people sense, feel, know, or seek to know, and to inspire acting on behalf of a livable future. Light in Dark Times is an urgent plea to go to the dark place and confront it. Still, there is always a stream of light amid the darkness. The project that became a graphic ethnography is also a quest to find the light, identify it, and hold onto its energy.

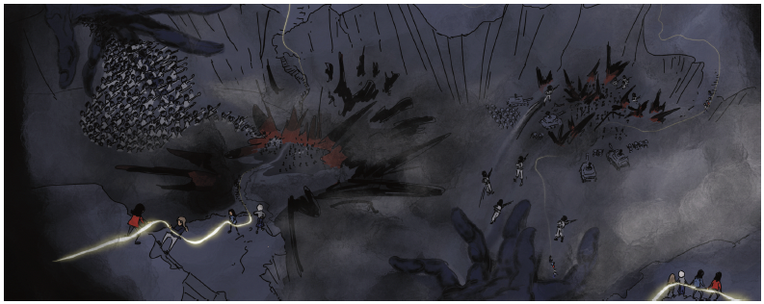

Charlotte and I entered a journey that became the narrative device in the book, where we, in our avatar forms, encounter thinkers, poets, activists, and anthropologists to explore those political catastrophes and moral disasters that bring outrage and sometimes despair. The catastrophes and disasters thus revealed would bring new understanding, the desire to know more, and the will to struggle against the horrors. These are aspects of the light in our story.

The journey and our collaboration were extraordinary. Charlotte and I talked, argued, designed, redesigned, agreed, disagreed, and cried in sorrow for the world. I had the feeling that this visually stunning book of art and anthropology might enter the world to make palpable and visible the knowledge, information, insight, and inspiration that many people crave.

The graphic format was liberating, enabling us to unleash our creative faculties. Neither Charlotte nor I had experience with the genre; we learned as we went along, first observing and assessing other graphic books and ultimately creating a storyboard that was literally taped to the four walls of our work area. Our collaboration was a dance of two temperaments, each of us bringing to the project our skills, talents, knowledge, experiences, and working styles. For me, the greatest challenge was—and is—to free myself from the conservative norms of the discipline that inhibit creativity while being confident in what to keep that is good and useful.

We envisioned a graphic ethnography that would make accessible abstract concepts that illuminate difficult, painful conditions. Because it does not privilege writing over other forms of constructing and representing knowledge, the graphic form enables readers and viewers to grasp meaning from the different, multilayered ways we evoke it with words and images.

Now, many months since the book was published, I go through it, page by page, reflecting on meanings newly evoked. I continue to be struck by the aesthetic beauty of Charlotte’s illustrations, and recall discussions we had about particular elements and the decisions we landed upon.

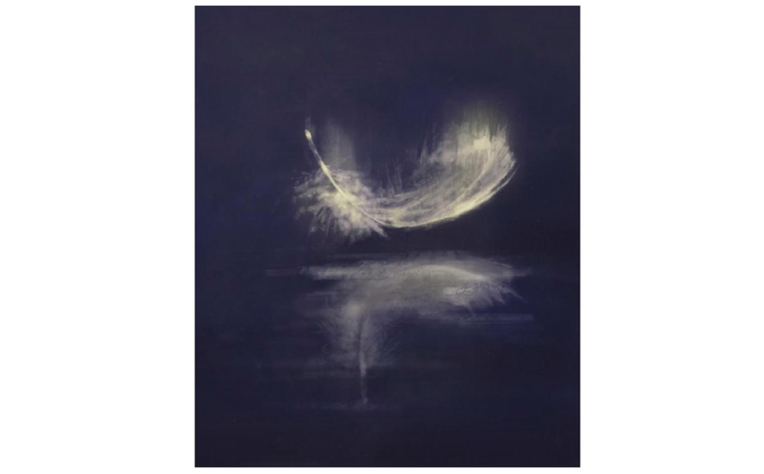

For example, the main body of the book begins with Chapter I, page 1, titled “Reflections.” Charlotte drew a feather floating mid-air against a dark background that also offers its own reflection. Why a feather? Charlotte and I debated using this image. She created it. I loved it and wanted it to stay. She wasn’t sure.

To capture the many meanings of reflection—to contemplate, to ponder and think about, to mirror or echo, to signify or reveal—any object might do. But the feather—this feather—is beautiful. The image is enchanting—the soft, light texture of the object kept together by a flexible spine. Its mirror self is not wholly the thing. Something is lost in the echo. The reflection is not precise. It is hazier than the thing itself although there is enough to reveal it is a downy feather with an arched, bendable spine. It is recognizable.

The feather is delicate, like our reflections might be—floating and ephemeral, sometimes hard to grasp. How accurate are our representations of “reality” (of people and places) and how precise are our interpretations, our analyses? As I reflect on the state of the world, my hold on understanding is sometimes clear and certain, sometimes patchy and tenuous: Do I really know what is going and why? Based on what evidence? What have I missed? Despite what may be lost in reflection and representation, the effort has value. What we have learned and come to know goes out into the world, reverberating and reflecting in unpredictable ways. Knowledge isn’t static; minds can open, flexible like the feather’s spine.

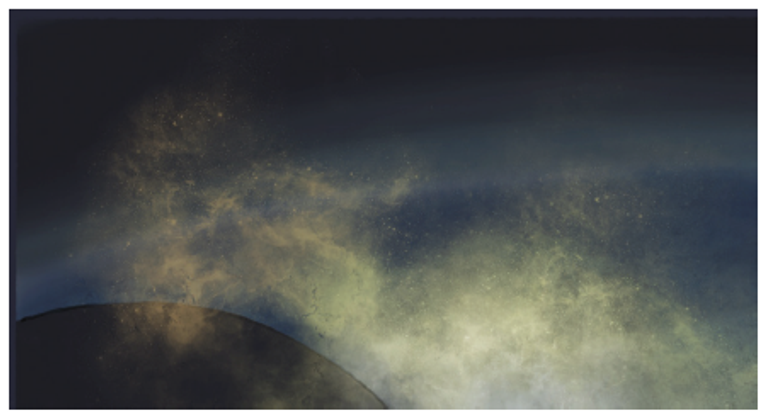

The feather appears at the start of the book, our journey. Holding onto a stream of light, we travel across large territory—the past and the present—necessary but insufficient steps towards arriving at the livable future we dare to imagine.