“We Talk to Each Other”: Korhogo after the End of the Rebellion

From the Series: Côte d'Ivoire Is Cooling Down? Reflections a Year after the Battle for Abidjan

From the Series: Côte d'Ivoire Is Cooling Down? Reflections a Year after the Battle for Abidjan

Till Förster, Institute of Social Anthropology, University of Basel

Since September 19, 2002 until recently, Korhogo, the third largest city of Côte d’Ivoire and rebel stronghold (Figure 1), existed without state administration. Over the years, other modes of governance emerged. Some worked well; others failed, as significant differences in administrative styles developed between the center of the city and its suburbs. As a result, Korhogo became more visible as a political space, i.e. as a city that became an increasingly independent, bounded arena open to shifting political articulations. Competing political actors framed their alternative interests more with reference to each other—despite the presence of the rebel command and the United Nations peacekeeping forces—than in relation to higher or more centralized levels of decision-making.

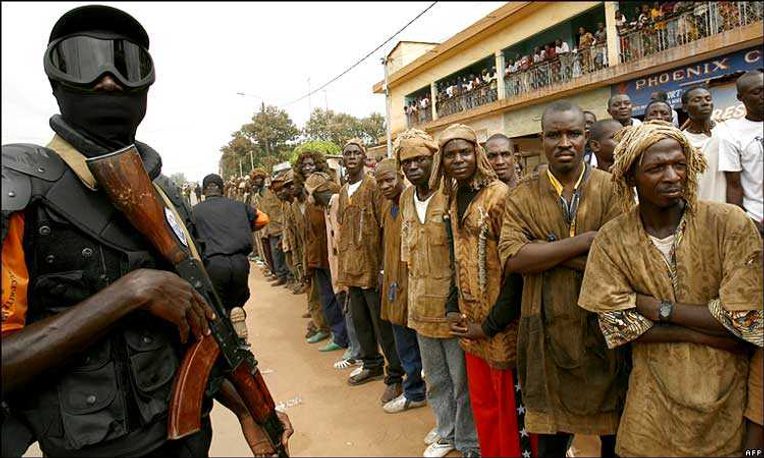

The main achievement during these years was a kind of political settlement between, on one hand, the rebel forces and their leader, Fofié Kouakou Martin (Figure 2), and, on the other, the dozos (Figure 3), so-called “traditional hunters.” While the former controlled the main overland routes and hence access to the city, the latter oversaw the downtown areas where they held night watches. This entente cordiale stipulated that no one else carry weapons wherever dozos were in charge, while the insurgents held the same right outside the city center. Dozos and rebels sustained this collaboration through weekly meetings and mutual trust. In Korhogo, I overheard them say of each other, “On se parle,” (We talk to each other), whereas in Man they said, “On se regarde” (We keep an eye on each other). Both offered security as a public good, leading many to believe that the city fared better under the new regime than under the former administration with its corrupt police and gendarmes.

There were also drawbacks. In particular, property and land tenure became more or less privatized. The former mayor, together with a few employees and land surveyors of the defunct city council, sold public land to private owners, making a fortune and feeding their patrimonial network, which had lost influence and resources under a rebel administration that privileged its youth over the city’s former political establishment.

After the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, which culminated in the capture of former president Laurent Gbagbo on April 11, 2011, the state slowly tried to re-establish its administration in the former rebel-held parts of the country, including the city of Korhogo. Police returned to Korhogo a few months after Gbagbo’s fall, but their numbers were limited. More importantly, most of them now came from the northern parts of Côte d’Ivoire. Under the old regime, the police had usually come from the South, a fact that many Korhogo residents experienced as a form of overt oppression under the anti-northern ethnic politics of previous regimes. Customs officers also returned to the region’s border towns, but they at first avoided levying fees. In this way, merchants who had profited enormously from the duty-free imports of Chinese goods through the harbor in Lomé, Togo, gained a few additional months of profit. But most expected customs fees to be re-introduced in March or April of 2012, although the exact date had been subject to ongoing negotiations between influential merchants and state representatives. Today, customs fees are still not levied regularly while, since March 2012, former rebel soldiers have been being trained as customs officers, being more easily accepted by the local population.

Meanwhile, the city has become a formidable construction site. The old tarmac, dating back to the independence day celebration of 1964, when Korhogo received a new street grid, has been replaced with a new surface. The road improvement project provided jobs to many who had been unemployed for years. The public water works, which had been in a state of neglect for decades, have also been refurbished, and outlying suburbs now receive electricity.

After years of suffering, the visible delivery of public goods has encouraged the feeling that the North is finally becoming what it always might have become if the South had not suppressed it: truly Ivoirian. The insurgent nationalism that fuelled the rebellion is now commonly expressed in daily conversation, as in claims such as, “We are the better Ivoirians, not the guys who invented that notorious ‘Ivoirianness’.” The man I quote was referencing the concept of ivoirité, the watchword of the ethno-nationalist ideology of the Bédié, Guéï, and Gbagbo regimes, which excluded many northern-descended citizens from political participation. Such statements are now so widespread that those who may harbor other opinions dare not articulate them. Such is the legacy of war and reconstruction in northern Côte d’Ivoire.